Jazz CD Review: Eric Dolphy — Still a “Musical Prophet”

By Steve Feeney

Eric Dolphy fully deserves the renewed attention that this important release demands.

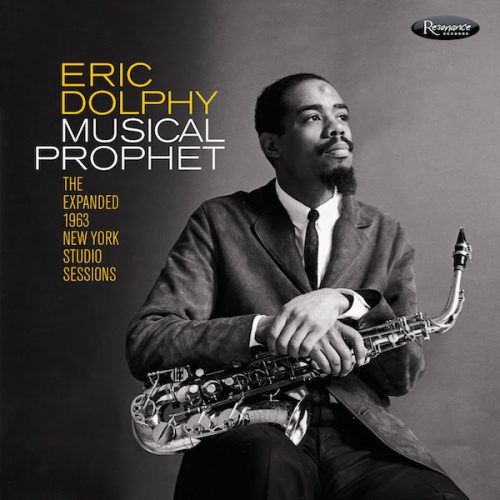

Eric Dolphy Musical Prophet: The Expanded 1963 New York Studio Sessions, Resonance Records

Hearing Eric Dolphy (1928-64) again brings me back to when I first started noticing acoustic jazz of the adventurous sort. Transcendence is the word best suited to express how it made me feel from the beginning. It introduced me to a great (not only musical) beyond.

Yet Dolphy’s music also felt like a perfectly professional representation of a high point in the bebop tradition — toward the edge of the cliff but not over it, educated in the sophisticated lines of thinking invented by Thelonious Monk, Charlie Parker, and a few others. His work may have been the last logical extension of bebop. Its sense of freedom and structure, its exhilarating interactions, was bracing. This was the real stuff for me.

Hearing Musical Prophet brought all that excitement back. It stood out boldly in the blizzard of releases of new and old material by other artists this winter.

The three-disc set contains the previously available Dolphy albums Conversations and Iron Man (produced anew from original mono tapes), plus a disc of previously unissued alternate takes of tunes from the 1963 recording sessions that produced those albums. The attractive packaging includes numerous photos as well as a thick booklet full of historical markers, warm reminiscences, close analysis, and celebratory tributes. Musician/educator James Newton, a longtime Dolphy champion, contributes particularly cogent thoughts on the contours of the musician’s art.

Dolphy, a multi-instrumentalist (alto saxophone, flute, bass clarinet) and former child prodigy, served historically significant stints in the bands of Charles Mingus and John Coltrane before (and, with Mingus, again after) these sessions. The booklet quotes praise from both musical giants.

Although Dolphy did not play on Mingus’ seminal disc Tijuana Moods, the cross culturalism of the great composer/bassist is felt here on two takes of “Music Matador,” a joyful south-of-the-border romp. As might be expected, the alternate take of “Matador” feels looser, as do most of the other selections on the disc made up of “new” material. But to my ears, nothing here sounds sloppy enough to be considered less than high quality.

Fellow Los Angeleno Mingus shared with Dolphy a creative distance from the sometimes-overheated New York scene. This healthy withdrawal from urban angst gave their music a distinctively playful feel — a sense of collectivism that, even now, reappears in the work of such West Coasters as Kamasi Washington, among others.

Dolphy’s collaborations with Coltrane could be a bit strained at times, but the former added a harmonic restlessness that even Trane had not mastered at the time. Listen to Dolphy’s work on the many takes of “India” and “Spiritual” from the 1961 Village Vanguard sessions. That’s crazy stuff! But it makes perfect sense — seen as the efforts of advanced bebop to connect with cultures and concepts from far and wide.

On the new release, two takes of Fats Waller’s “Jitterbug Waltz” mark the wealth of inspiration Dolphy found in music that was already considered “vintage” by 1963. Take your pick — both versions serve up a wellspring of exuberance that is still fundamental to, but often absent from, contemporary jazz.

The set initially sold itself to me by virtue of the presence of an alternate take of Dolphy’s tune “Mandrake,” one of my all-time favorite jazz compositions. The piece slips and slides through a magical labyrinth, a nimble journey that generates astonishment, mystery, and grace. The longer alternate take fleshes out — just a bit — what is one of Dolphy’s most masterful efforts.

There’s so much more on this disc. Dolphy is resplendent on alto sax, flute, and bass clarinet in solo, duo and group situations. The work of the young Woody Shaw (trumpet) stands up to ace contributions from an inspired Richard Davis (bass) and others: saxophonist Clifford Jordan, flutist William “Prince” Lasha, bassoonist Garvin Bushell, bassist Eddie Kahn, and drummers J.C. Moses and Charles Moffett. Bobby Hutcherson (vibes), who would soon anchor Dolphy’s 1964 masterpiece Out To Lunch, is already taking on the role of liquid harmonic center for a leader who fully deserves the renewed attention that this important release demands.

Steve Feeney is a Maine native and attended schools in Maine, New Hampshire and Massachusetts. He has a Master of Arts Degree in American and New England Studies from the University of Southern Maine. He began reviewing music on a freelance basis for the Portland Press Herald/Maine Sunday Telegram in 1995. He was later asked to also review theater and dance. Recently, he has added BroadwayWorld.com as an outlet and is pleased to now contribute to Arts Fuse.