Concert Review: David Byrne’s “American Utopia” — Live

Conceptual and abstract as David Byrne can often be, he’s one art schooler who isn’t afraid to get down.

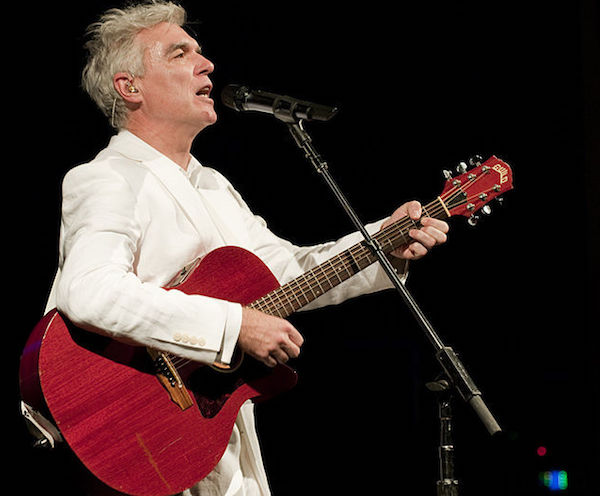

David Byrne. Wiki Commons.

By Matt Hanson

Over a long career, David Byrne has consistently been one of the most innovative and genre-defying musicians in the world of pop music. He made his first distinct mark during CBGB’s heyday with Talking Heads, playing quirky and sometimes demented art rock clad in khakis and a polo shirt amid beefier acts like The Ramones and The Dead Boys. He then navigated the Heads’ emergence as a mainstream success during the late ’70s and ’80s.

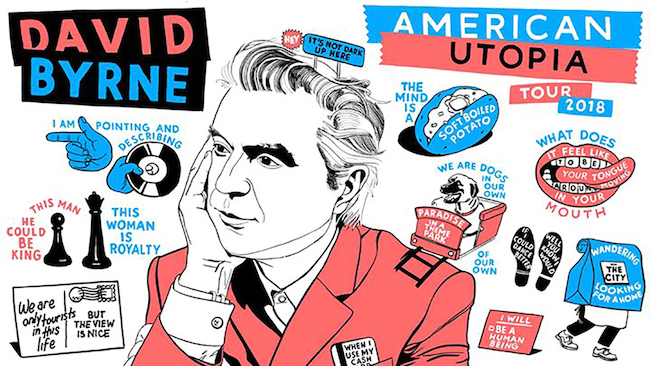

Since then, Byrne has become an experimental pop maestro seemingly in a world of his own. There’s no telling where his eccentric vision will take him: he’s collaborated with the likes of Brian Eno and St Vincent, directed movies (his feature True Stories is due out in the fall from Criterion), tirelessly promoted obscure world music, and written books such as the bestselling How Music Works. His musical career has recently re-emerged with American Utopia, his first purely solo record since 2004’s superb Grown Backwards.

Byrne and his large and vibrant backing band are currently crisscrossing the country on an extensive world tour, which I was lucky enough to catch last weekend. Among the things that makes Byrne special is that, conceptual and abstract as he can often be, he’s one art schooler who isn’t afraid to get down. He was hip to the Afrobeat of Fela Kuti before pretty much anyone else; he incorporated Fela’s innovative groove into Talking Heads tunes without falling into the trap of coming off as exploitative or hipper-than-thou. Try watching Stop Making Sense, to my mind the greatest concert film of all time — I dare you not to get up off the couch to bust a move or two.

Concerts give musicians a chance to add a visual context to the music, and Byrne’s approach takes full advantage of the performance space. The show opens with silver bead curtains hanging down the back and sides of the stage, isolating the middle section, with a chair sitting at the center. Byrne comes out dressed as nattily as ever, with a mane of silver hair over an immaculately tailored gray suit and bare feet. He is holding a plastic model of the human brain. As he croons about the brain’s various lobes and hemispheres, he walks backwards until his little guided journey into the center of the brain is completed and he settles into the chair. Then the band, ethnically diverse but identically attired in gray suits with black shirts and bare feet, emerges onto the stage and starts jamming behind him.

Byrne is now in his late sixties, so his famously idiosyncratic dance moves are understandably not quite what they were back in the day. Still, he manages to reflect the pulsating, infectiously physical qualities of the music with the occasional jabbing arm gestures and a leg wiggle or two. Most of the dancing is energetically handled by his backing band, whose members fill the space with exuberant bodies in motion. At times, the movements seem deliberately choreographed; at other times it looks a little like what would happen if a ’70s disco spontaneously threw open its doors and let its patrons party freely in the streets.

Probably only David Byrne could write a line like ”the Pope don’t mean shit to a dog” and make it fit into an uplifting tune called “Every Day Is A Miracle,” which features a near-yodeling falsetto and a chorus that unironically encourages us to “love one another.” When the recognizable beats of classic Talking Heads tunes “Once In A Lifetime” and “I Zimbra” started up — still funky after all these years — the crowd rose to its feet and stayed there for the rest of the show. Watching his crack team of backup singers and dancers frisk and gambol across the stage, obviously thrilled to be there, is so much fun that you might almost forget the horror of the daily headlines. But Byrne’s aesthetic, abstract as it often is, never strays far from unabashed social criticism.

At one point early in show, Byrne thanked the crowd for coming out and mentioned that he was touring in collaboration with a voter registration organization called Head Count. Booths for automatic registration sat in the lobby for interested parties. During “Bullet,” a song from the new record, the stage went dark except for a single lamp, which illuminated Byrne’s face as he sang about gun violence with a disembodied matter-of-factness: “The bullet went through him/ His stomach filled with food/ Many fine meals he tasted there/ But the bullet passed on through.” The sad fact is that he could have been singing about any number of recent lives lost to gun play, a point he made during the second encore.

He explained that, even though Janelle Monae’s protest anthem “Hell You Talmbout” came out five years ago, it’s still sadly relevant. Then he and the band gathered in a straight line and faced the audience directly. The song, an outraged but catchy clatter of percussion and synchronized vocals, was punctuated in this performance with references to victims of police brutality like Walter Scott, Trayvon Martin, and Eric Garner. The urgent refrain was to “say his name, say his name.” It was a potent reminder that, despite the gleefully danceable utopia Byrne and company created for a couple hours, certain things aren’t going to get fixed no matter how hard you get down.

Matt Hanson is a critic for The Arts Fuse living outside Boston. His writing has appeared in The Millions, 3QuarksDaily, and Flak Magazine (RIP), where he was a staff writer. He blogs about movies and culture for LoveMoneyClothes. His poetry chapbook was published by Rhinologic Press.

We need to see this!