The Fuse in London: Jazz Festival Diary 7

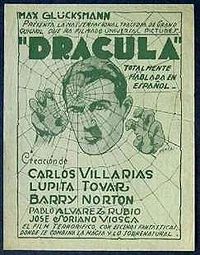

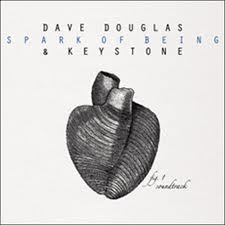

A modern version of the venerable double bill: first, Drácula, a 1931 Spanish-language film accompanied by guitarist Gary Lucas performing his half-improvised original score. Next came the film Spark of Being, a re-imagining of the plot of Frankenstein, co-directed by filmmaker Bill Morrison and trumpeter-composer Dave Douglas, who led his band Keystone in 13 pieces written to illuminate the film.

By Steve Elman.

There was a lot to take in on November 21 at Queen Elizabeth Hall, the last performance I attended at the London Jazz Festival. The program consisted of two music-film projects, which made for almost four hours of perception-stretching. It’s taken more than a week to reset my body clock, decipher the pages of notes I wrote in the dark, and filter some random observations on the relationship of music to film.

I also had the chance this week to test the BBC3 links to programming spotlighting some of the festival artists, and I’ll have a postscript on those matters at the end of this diary entry.

In some ways, the November 21 concert was a modern version of the venerable double bill. The opener was Drácula, a 1931 Spanish-language film made at the same time as Tod Browning’s classic with Béla Lugosi, accompanied by guitarist Gary Lucas performing his half-improvised original score. The second feature was the avant-garde film Spark of Being, a re-imagining of the plot of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein using found footage and direct manipulation of the film stock, co-directed by filmmaker Bill Morrison and trumpeter-composer Dave Douglas, who led his band Keystone in 13 pieces written to illuminate the film.

Got it? Before discussing the details of this concert, I should comment on its technical aspects and make some by-the-way observations on PA sound throughout the festival. With the exception of my previously-mentioned concerns about the pickup of the Scottish National Jazz Orchestra on November 15, I have been mightily pleased with the London Jazz Festival’s hall sound.

Last year I heard Sheila Jordan’s beautiful recital in Paul Hamlyn Hall at the Royal Opera House; Julian Siegel, Carla Bley and the Lost Chords, Dave Holland’s Overtone Quartet, and Branford Marsalis’s group at QE Hall; and Marcus Miller’s band at the Barbican. This year I got to the Rose Theatre in Kingston for the first time, in addition to seeing more shows at QE and Barbican. Whether the music has been intimate or large-scale, electric or acoustic, quiet or deafening, the hall PA folks have done a stellar job, conveying it in excellent balance, at proper volume levels and without distortion.

This last show may have been one of the biggest challenges for the tech crew in the 2010 edition of the festival. It required theatre-quality projection of both a vintage B&W film and a contemporary art film. It also required balancing live house PA with the soundtrack of the 1931 film and integrating offstage sound effects and electronics with Keystone’s live performance. Although there was one small glitch in the projection of Spark of Being, it was quickly corrected; otherwise, the crew gets high marks on all fronts.

I should point out that Lucas apparently wishes his Drácula score to be heard at a volume level that competes with the dialogue of the film, which is not the fault of the PA people. This doesn’t present a problem of understanding for English-speaking listeners, since the film is subtitled, but there’s something of a split personality to the result—the music has the foreground presence you’d expect in a silent film experience, but this is a sound film, where you expect the music to allow you to perceive the actors’ tones of voice and to hear the noise of the action. Lucas’s approach takes some getting used to, but once I made the adjustment, I found his take on the film valuable and enlightening.

Lucas transcends categories, and typing him as a jazz guitarist would be an injustice. One two-year period is always mentioned in his musical bio—his stint with Don Van Vliet (Captain Beefheart) in The Magic Band, including his work in the group’s last recording, “Ice Cream for Crow.” Beefheart’s notoriously demanding music was seminal in Lucas’s development, forcing him to expand his technique and laying the foundation for a lot of his subsequent music. Among other things, he’s known currently as the leader of Gods and Monsters, which his website describes as “an avant-rock supergroup / jamband playing intense psychedelic rock.” Guitarists in many genres admire his control of his instrument and his integration of electronics.

His music has come to new audiences recently, on the strength of his semi-improvised film scores for classic horror movies. He’s previously written and performed accompaniment for Browning’s silent film The Unholy Three and the Paul Wegener/Carl Boese silent The Golem, which is available on DVD.

He’s currently preparing performances of a score for Jose Mojica Marins’s Esta Noite Encarnerei No tu Cadaver (Tonight I Will Possess Your Corpse). But Drácula has generated the most attention so far, getting its premiere at the Havana Film Festival and then touring the world, including shows in Romania (in the Transylvanian town of Bontida, outside the Castle Banffy), Sevilla (Spain) and New York City. His next performance of the score-plus-film will be on February 21, at the Glasgow Film Festival in Scotland. There’s much more about the project, plus some clips, on Lucas’s website.

For some viewers, Tod Browning’s Dracula is definitive at the same time that it’s camp. In that film, Lugosi is both funny and terrifying at the same time, and Dwight Frye’s scene-chewing Renfield is unforgettably baroque. This alternate version is worthy on its own merits, in some ways better acted than the Browning version and more satisfying. Before it began, Lucas explained that Drácula was created at the same time as the English-language version, using Spanish-speaking actors, intended for a Spanish-speaking audience. It uses a very similar script and a good deal of the same scene blocking as Browning’s film does.

But director George Melford, who had the primary role as auteur of Drácula, brought more depth to the exterior shots, set more effective lighting for the interiors, and, in some cases, drew more feeling performances from the actors. Enrique Tovar Ávalos is now known to be the co-director, conveying Melford’s ideas to the cast and perhaps contributing some of his own.

Carlos Villarías has the Lugosi part, and he does the big eyes and enshrouding cape just as you’d expect. He also knows how to be genuinely scary, as in the shipboard scene where he emerges from his coffin to prey on the crew sailing him to England. And he also shows off some Latin charisma, which works surprisingly well with the character and the makes the ladies’ interest in him more believable. Pablo Álvarez Rubio, as Renfield, does crazy as well as well as Frye did, with a marvelously convincing demonic laugh, but he makes the conflicts in Renfield’s soul more convincing—you can see that there’s a real battle going on between his better nature and his slavery to Drácula. Lupita Tovar plays the Helen Chandler role, renamed Eva, and she is mostly a colorless victim, but she gets one terrific scene where she lets out her sensuous side while fully under Drácula’s spell.

Lucas added a constant musical commentary to the film, weaving improvisation into his pre-written material. A musical foundation is set in the original soundtrack with familiar dark motifs from Tchaikovsky’s Swan Lake under the main titles and in a later concert hall scene.

As the film opened in London, Lucas played along with the period orchestra, adding a contemporary edge, and then his music continued as the Tchaikovsky died away. In a post-film Q&A, he said that those Swan Lake chords are always in his head when he plays with the film; on this night, those harmonies were a strong unifying element, even though they were filtered through Beefheartian slide stuff, blues figures, fancy fingerpicking, and imitative effects—rolling figures to accompany the bouncing carriage scenes, howling to reinforce the distant sounds of wolves, creaking to amplify those rusty door hinges, even some very convincing silent-movie organ sounds. He also made effective use of looping, which cleverly covered his transitions between electric and amplified acoustic guitar.

It seems that Lucas wrote some specific motifs for Renfield and Eva, which emerged and returned during their important scenes. I did not perceive a theme for Drácula himself, but since his film presence is so strong, Lucas may have decided that no musical reinforcement was necessary. I was particularly glad that Lucas did not introduce anything consciously “Spanish.” That might have been appropriate if the filmmakers had completely Hispanicized the film and brought Drácula to a crumbling Iberian castle, but, as in the original, the action of this film takes place in Transylvania and England.

None of this music would stand on its own, and it is not intended to do so. The creative experience here was an interactive one. Lucas watched the film carefully as he played, even though, as he noted later, he knows every frame and every gesture of it by heart. He sometimes anticipated the next scene musically by a few seconds; at other moments, he lagged behind the action reflectively. This reinforced the artificiality of the experience and emphasized that this was a dialogue of media, a conversation between creators.

Dave Douglas’s performance was a very different experience. Quite a bit of his score for Spark of Being could stand independently, and he rarely looked at the screen while the music was being played. The independence of the music is inherent in the film’s structure; Bill Morrison and Douglas divide the action into 13 individual scenes, each of which has a stand-alone piece by Douglas, presumably timed to the length of the particular scene, as accompaniment.

Morrison seems to be comfortable collaborating with musicians who work in a range of styles. He’s worked on projects with John Adams, Bill Frisell, the late Henryk Gorecki, and Vijay Iyer, among others. Because of Douglas’s commitment to Spark of Being, it may be the most prominent of Morrison’s recent films.

The film and its music are available on DVD, and this site also includes clips of the music and a trailer that provides a taste of the visuals. Another site provides the opportunity to watch the entire film online or download it.

Anyone expecting a Karloffian, Frankenstein’s-monster tale will be disappointed by Spark of Being. It uses the plot of Mary Shelley’s novel as a framework for a somber meditation on the hubris of genius, as you would expect, but also on alienation from life itself. The broad outline is a gifted scientist, obsessed with death, animates a creature assembled from corpses; he tries to educate the creature and give it a chance to live in society, but his efforts only prove to the creature how ill-suited it is for life and how foolish the scientist’s efforts were; there is a struggle between the two, resulting in the scientist’s death and the creature’s exile to self-destruction in the frozen wastes of the North.

How does Morrison tell the story without any actors or live shooting? As it turns out, remarkably well. He has a voluminous knowledge of footage from damaged vintage films, films that have survived only in fragments, stock from film archives, and images from his own collection. He selects material for his films from these sources as appropriate, adds color washes and his own abstract images, and distresses and manipulates the film stock.

The resulting collection of representational and non-representational visuals creates a conversation in the viewer’s mind between what is on the screen and what he or she expects from the story. In this case, I was constantly trying to integrate Morrison’s interpretation with what I knew or remembered of Shelley.

Each of the 13 segments of the film has a helpful title indicating what aspect of the novel is being reimagined. Some of the segments are near-literal translations. For example, ‘The Doctor’s Wedding” consists entirely of re-cut footage from a traditional marriage celebration in a German village, dating from the 1910s or 1920s. Horse-drawn vehicles, grim-faced Lutheran clergy, slap-heel folk dancing, lederhosen, lumpen peasantry—it’s much as it might have been in such a village a hundred years earlier. But there is no “center” or narrative per se. To provide a stand-in for Victor Frankenstein, Morrison provides only a brief shot of the groom, awkwardly posed with his bride, and a short sequence of the married couple dancing.

Mostly what we see here is a kind of documentary of alienated foreboding. The troupe of ministers look like they’re going to an execution. The marriage bed, hauled through the streets on a wagon, seems anything but inviting. The dancing takes place in what looks like a prizefighting ring set up in the town square. The people seem alternately boorish or sinister; over and over, I was reminded of Erich von Stroheim’s portrayal of the coarse German immigrants in Greed.

The closing shots of the chapter make these implicit qualities more explicit: Morrison slows down and repeats some footage of women dancing, shot at about calf-height; as their skirts swirl and they pass back and forth, we glimpse in the background the faces of bored female spectators and a loutish fellow shouting either encouragement or drunken commentary.

Other chapters are less literal. “Observations of Romantic Love,” presumably giving us the creature’s view of the same, consists of slow-mo footage of a nude couple running through a field, embracing, and finally falling to the earth, out of the frame. The few minutes are interrupted by non-representational images. Morrison also colors over the original shots of the lovers and solarizes them into abstractions. Another example, “The Creature in Society,” is illustrated by wide shots of a massed crowd from the same period as the wedding, with many faces looking towards the camera showing what might be curiosity, or hostility, or surprise.

A narrative emerges. Roughly following the structure of the novel, the film begins and ends with the dire consequence of Frankenstein’s experiments—his death in the arctic after a struggle with his creature. Morrison gives us the same images in both places—a ship enters frigid waters, encounters icebergs, and becomes mired in pack ice. There are shots of men on dogsleds, mushing through the whiteness. Morrison concludes each of these sequences with footage of a man’s body on the deck of a ship, with crewmen engaged in vigorous efforts to resuscitate it. This stands in for Frankenstein, who is rescued at the beginning of the novel and dies at the end.

In between, the film tracks the doctor’s education, the creature’s animation and education, the doctor’s flight from his creation, and the desolate end for both of them. Morrison gives considerable time to the creature’s alienation—of the 13 chapters, this is the theme of five: “The Creature Watches,” “Observations of Familial Love,” “Observations of Romantic Love,” “The Creature in Society,” and “The Creature Confronts his Creator.”

Throughout, Douglas’s music was rich and strongly textured, played with great commitment by the quintet—Douglas on trumpet, with a short interlude on wooden flute; Marcus Strickland on alto; Adam Benjamin playing Fender Rhodes electric piano; Brad Jones on amplified baby bass; and drummer Gene Lake—with some discreet electronic effects provided by Jeff Countryman, who was working from an offstage board.

In one or two cases, the compositions were atmospheric accompaniment to the visuals, but, for the most part, each chapter’s music seemed to be a full-scale elaboration on a particular emotional element. For example, one of the most appealing pieces was a strong, jazz-rock composition accompanying “The Creature’s Education,” which seemed to embody a sense of possibility and optimism. The music is not consciously filmic or directly illustrative of the story—for example, no oompah-effects punctuated “The Doctor’s Wedding,” although Douglas’s trumpet and Strickland’s sax entered at exactly the moment we first saw the German village band on the screen.

The musical language of the score is firmly within Douglas’s own vernacular, that is, both derivative of Miles Davis’s work and fascinatingly different from it. As he has in other settings, Douglas has adopted here the trappings of a particular period of Miles’s work; in this case, it’s the sound of the late, 1968 transition from the acoustic quintet with Wayne Shorter to the partly-electric “Bitches Brew” sessions. Those recordings, originally distributed among the albums Miles in the Sky, Water Babies, and Circle in the Round, are distinguished by prominent use of Fender Rhodes (played by Chick Corea, Herbie Hancock, and/or Joe Zawinul) and “forward” drumming from Tony Williams or Jack DeJohnette.

Douglas uses these instrumental colors as a ground and notably replaces the tenor voice with alto. It is as if he is saying, “Miles only glanced at what this combination of sounds can do. Let’s dig more deeply and see what we can come up with.” In one way, Douglas inverts the priorities of his inspiration. Instead of the bare sketches of tunes that Miles, Shorter, and Zawinul wrote for the original sessions, Douglas has created compositions that are extensively scored, sometimes with two or three new themes introduced within the same piece. The jazz is woven into the interpretation, and the actual solos are relatively short.

To sum up, Spark of Being was more an intellectual exercise for me than a fully-involving experience, but the poignancy of the conclusion was unmistakable. At least two sections of the film seemed to me to be less than satisfactory: “The Traveler’s Story,” where I found it difficult to coordinate the images with what I remembered of the novel, and “Observations of Romantic Love,” which seemed a kind of burlesque of the old Clairol ads (“the closer he gets, the better you look”) with both him and her deprived of their clothing.

I wish that I’d had the chance to hear more of Douglas’s music without the film. The band played a prologue and an encore sans visuals, and I found both pieces absorbing and creative. Unfortunately, while the film was being projected, I was working so hard to understand what Morrison was showing me and why I was seeing it that my appreciation for the music had to take second place.

Postscript:

I will have another diary entry with some reflections on the festival experience, some notes on its organizational details, and some lessons that Boston Jazz Week might take from it, but for now, I want to alert The Arts Fuse readers to online listening and downloads from this year’s London concerts.

Most of the concert material is being broadcast within the BBC’s “Jazz on 3,” hosted by Jez Nelson, which airs on Mondays at 11:15 p.m. (6:15 p.m. Boston time) and “Jazz Line-Up,” hosted by Claire Martin and Julian Joseph, which airs on Sundays at 11:30 p.m. (6:30 p.m. Boston time). I’ve tested the feed from my home computer in Boston, and I’m pleased to say that the BBC recordings are excellent and the online transmission quality is outstanding.

Here is the full list of all the BBC3 London Jazz Festival broadcasts, including those no longer available for download.

As of today (November 30), these live performances are still available for download on online listening at this link:

Drummer Asaf Sirkis, recorded November 19

AfroCubism, Nick Gold’s project bringing together musicians from Cuba and Mali, recorded November 21

Here is the schedule for some notable broadcasts planned in the weeks ahead. The time of the first broadcast is Boston time; after its initial airing, each program will be available for download or on-demand listening for seven days. Again, see the link above.

December 5, 11:30 p.m.: Trumpeter Terence Blanchard’s quintet, recorded November 14

December 6, 11:15 p.m.: Pianist Geri Allen (solo), recorded November 18

December 13, 11:15 p.m.: Darcy James Argue’s Secret Society, recorded November 18

January 17, 11:15 p.m.: The Bad Plus and multi-instrumentalist Django Bates, recorded November 20

January 23, 11:30 p.m.: Bassist-vocalist Esperanza Spaulding & Chamber Music Society, recorded November 13

January 24, 11:15 p.m.: Drummer Louis Moholo-Moholo, in a duo set with pianist Keith Tippett and then in a group setting, recorded November 19

Tagged: Dave Douglas, Dracula, Gary Lucas, London Jazz Festival, silent film, Spark of Being