Book Review: An Authoritative and Highly Opinionated History of the Musical ‘Chicago’

Ethan Mordden’s volume openly defies anyone to dismiss the American musical as mere fluff.

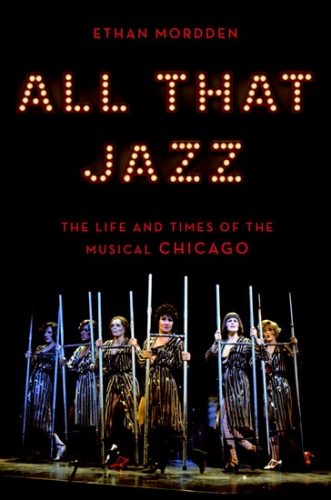

All That Jazz: The Life and Times of the Musical ‘Chicago’ by Ethan Mordden. Oxford University Press, 272 pages, $29.95.

By Christopher Caggiano

What Ethan Mordden writes makes for mandatory reading among theater mavens. He is one of the most knowledgeable authors currently writing about the stage, musical theater in particular; his lively mix of style, scholarship, and snark makes him sui generis in his field.

From his 2015 volume Sondheim: An Opinionated Guide (emphasis on the “opinionated”) to his earlier series of books, which broke down the American musical over the decades, including 1998’s Coming Up Roses: The Broadway Musical of the 1950s, Mordden rarely fails to fascinate, infuriate, please, and agitate, often within the same paragraph.

That stimulating gathering of contradictions is present in his latest book, All That Jazz: The Life and Times of the Musical ‘Chicago’. As his subtitle implies, Mordden takes us through the entire history of the material, from the original 1925 Maurine Watkins play and two non-musical Hollywood films to the 1975 stage musical and its eventual reclamation via a blockbuster revival and award-winning movie version.

The striking thing about Mordden is how much social, political, and intellectual weight he ascribes to his high-stepping subject matter. Mordden’s work openly defies anyone to dismiss the American musical as mere fluff.

In All That Jazz, he admits early on that, now that the musical Chicago has gone from semi-obscure footnote to cultural phenomenon, it’s easy to underestimate how the show is “mere crazy fun.” “…[A]nd everyone knows,” he says, “[that] crazy fun has no intellectual content…” He ends All That Jazz by refuting that point, arguing that “intellectuals scorned [the musical] as cotton candy, but they’re wrong. It’s the art by which we comprehend ourselves.”

Such lofty assertions might come off as risible if Mordden didn’t have the encyclopedic knowledge and analytic verve to back them up. He essentially uses Chicago to explore large and compelling questions about the musical form: When did the American musical develop the facility to address such ambitious subject matter, both in terms of craft and theme? As Mordden puts it, “[T]his book is about more than Chicago: it tells how the musical developed the characterological and thematic methodology to observe and comment on American life.”

For Mordden, a large portion of the show’s appeal lies in how thoroughly it taps into our fascination with two of America’s most iconic myths: the 1920s as a decade of roaring decadence and the city of Chicago itself. He starts off the book with chapters that separately address the era and the city. And, because he considers Chicago the pinnacle of musical theater satire, he also includes a chapter that provides a précis on the history of barbed social comment in song and dance shows.

Of course, Mordden analyzes the show itself, treating the reader to a song-by-song evaluation of the score, paying particular attention to its vaudeville tropes and the real life performers that are evoked in Chicago‘s songs. The show is, after all, subtitled “A Musical Vaudeville,” and it represents the apex of director/choreographer/co-librettist Bob Fosse’s career as a participant in — and commentator on — the razzle dazzle style of American musical entertainment.

(Anyone looking for dish on the backstage battles and machinations during the development of Chicago had best look elsewhere, perhaps to Sam Wasson’s excellent biography, Fosse (2013). Mordden only briefly addresses all the Sturm und Drang.)

Mordden is, above all other things, authoritative, the musical-theater aficionado nonpareil. You may not agree with all of his critiques, but you have to admire his exhaustive command of the facts, and the supreme erudition he uses to back up his opinions. Thus, it feels definitive when he characterizes the style of legendary theater director George Abbott as “marked by speed, clarity of action, and what we might call ‘freshness of cliché.’”

Mordden has an admirable knack for crafting prose that makes his opinions juicy as well as compelling. His diction runs the gamut from the colloquial to the rarefied. (I always pick up few choice vocabulary words whenever I read Mordden.) He has a canny knack for memorably summing up his points, frequently ending a fact-packed paragraph with a pithy tagline: “Journalism is the Chicago of professions, it seems: it does whatever the hell it wants to.”

Mordden’s penchant for including insider references can be a bit off-putting, partly because he isn’t always sure how to treat the reader. Someone who knows the angles? Or a beginner? At times, he comes on as the careful explainer, repeating his definitions of terms, such as when he tells us (more than once) that “business,” in theatrical terms, is another word for “shtick.” Yet at other times he relies on the reader to know how to fill in the gaps: “If this weren’t a silent [film], she’d be humming Lohengrin.” (Mordden, of course, is also a redoubtable expert on opera.)

He also also can’t resist a little dish now and then, as when he describes how English actor Henry Wilcoxon “managed to be a dreary actor and a smoldering sex rocket at the same time.” Mordden can’t resist going off on fascinating but irrelevant asides, often as as sidebar for an incisive observation. While discussing a song that was introduced by singer Kate Smith, he describes her as a blend of the majestic and the casual: “Listening to her sing was like going to high school with Aida.”

A scene from the film version of the musical “Chicago.”

The catch is there’s a tricky line between lively pedagogue and finger-wagging pedant, and Mordden sometimes steps over the border. He takes lots of delight in setting the record straight, particularly when he deflates experts, as when he debunks the common contention that it was a resurgence of religious fervor that caused Maurine Watkins to withhold the musical rights for her play. Mordden observes that Watkins was always deeply religious, so no resurgence would need to have been in the offing. It is this urge to be righter-than-thou that goes overboard, as when he strenuously decries, both here and elsewhere, the common usage of the moniker “Mama Rose” for the main character in Gypsy, claiming — albeit correctly — that she’s never referred to as such in the libretto. (True. But whom does it harm to refer to her as “Mama Rose”? I do it all the time in my musical-theater history course. It’s a useful shorthand.)

And yet, even with his persnickety-ness, Mordden remains essential. He’s like that cranky, exasperating, but undeniably entertaining/knowledgable guy you’ve known since college. Other people can’t see why you still have the guy around, but the quirks and insights are what makes the relationship so rich.

Oh, and do yourself a favor. Don’t stop reading after the final chapter. Dig into the footnotes, the discography, and the suggestions for further reading. Otherwise you’ll miss out on some of Mordden’s most delicious observations. For example, his idea for a contemporary dream cast for Kurt Weill’s odd but brilliant musical Johnny Johnson. Or his genuinely eyebrow-raising anecdote about a music director who whips out his Prince Albert during rehearsal. You’re not going to find that in your Funk & Wagnall’s.

Christopher Caggiano is a writer and teacher based in Boston. He serves as Associate Professor of Theater at the Boston Conservatory at Berklee. His writing has appeared in American Theatre and Dramatics magazines, and on TheaterMania.com and ZEALnyc.com.

Tagged: All That Jazz, Chicago, Christopher Caggiano, Ethan Mordden