Book Review: “The Last Utopians” — Visions for Tomorrow?

Do these “four late nineteenth-century visionaries” still speak to us?

The Last Utopians: Four Late Nineteenth-Century Visionaries and their Legacy by Michael Robertson. Princeton University Press, 316 pages, $29.95.

By George Scialabba

Today utopian social criticism is, if not quite dead, at any rate in a long coma. The horrors of National Socialism, Soviet Communism, and Maoism were rationalized with a pseudo-utopian rhetoric, which largely discredited the very idea of utopia in the mid-20th century. The 1960s and 70s saw a modest flowering of theoretical and imaginative writing and experiments in communal living. But the relentless march of the New Right, beginning with Reagan’s victory in 1980, seems to have quashed utopian hopes ever since. It is an odd time, then, to be looking back a century and more at the golden age of utopian speculation in the English-speaking world. The dystopia of permanent radical inequality and environmental catastrophe seems far more likely than a world of beauty, plenty, and community.

Of the four “last utopians” – Edward Bellamy, William Morris, Edward Carpenter, and Charlotte Perkins Gilman – Bellamy and Carpenter are now largely forgotten, while Morris and Gilman are remembered for reasons unconnected with their visionary writings: Morris for his brilliantly original designs and Gilman for her ur-feminist short story, “The Yellow Wallpaper.” But in their time, all four were culture heroes: best-selling authors, popular lecturers, public figures, and objects of veneration and pilgrimage. Michael Robertson, an English professor at the College of New Jersey, has undertaken to tell their story, without messianic zeal (unfortunately) but with sympathy and insight.

By far the biggest footprint was Bellamy’s. Looking Backward (1888) sold half a million copies, an enormous number for that time – more than any other book in American history to that point, except for the Bible and Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Bellamy was an earnest, not very colorful personality. The son of a Baptist minister, a college dropout, editorial writer, and author of sentimental popular novels, he lived nearly all his life – even after he became world-famous – in his native Chicopee, Massachusetts.

Looking Backward began life as one more middlebrow romance but, thanks partly to the influence of Henry George’s mega-bestseller Progress and Poverty (1879) and partly to the economic privation and labor unrest of the 1880s, became a paean to solidarity and rational planning. It is the story of Julian West, a rich 19th-century Bostonian who falls asleep in a mesmeric trance in the sealed underground chamber of his Back Bay mansion. The mansion and its surroundings are destroyed overnight in a vast fire. The subterranean chamber is not discovered for 113 years, until 2000. The discoverer, a kindly retired physician named Dr. Leete, revives West and gradually introduces him to the 21st century.

The book is largely dialogue (though Bellamy the popular novelist works in a surprise romantic ending). In fact, it feels more like a monologue than a dialogue, with Julian feeding Dr. Leete cues in the fashion of Socrates’ interlocutors. Julian has all the laissez-faire prejudices of today’s free-market conservatives: no one will work except on pain of starvation; everyone deserves what he gets, however little others may have; government economic planning and coordination are tantamount to slavery. Patiently (though sometimes with a touch of exasperation) Dr. Leete explains that the wastefulness and cruelty of the old system became increasingly obvious and undeniable, and the superior efficiency and fairness of a cooperative, egalitarian system quickly proved itself. Everyone got as much schooling as they had a taste ffor; everyone worked from age 21 to 45, with more or fewer hours per week depending on the desirability of the job; and – this blew Julian’s mind and that of many of Bellamy’s readers as well – everyone received exactly the same income.

Dr. Leete’s explanations – continued at length and in greater detail in a sequel, Equality (1897) – convinced most of Bellamy’s contemporaries. Posterity has occasionally condescended to Bellamy, but discerning critics have valued him justly. In his magisterial study of American progressives, Men of Good Hope, Daniel Aaron concluded: “The more closely one examines the utopia of Bellamy, the more just and penetrating his criticisms become and the more feasible his recommendations. Compared with the dozens of utopian novels written during the last three decades of the nineteenth century, Looking Backward and its sequel are superior in almost every respect.”

Robertson, like most modern commentators, thinks that discipline and regimentation figure too largely in Looking Backward. One can see why: everyone is enlisted in an “industrial army,” graded into ranks, and there are no regular nation-wide elections or plebiscites. On the other hand, everyone spends their first three years of work in unskilled physical labor – an anticipation of William James’s “The Moral Equivalent of War.” Officers in the industrial army are not allowed the smallest degree of arbitrary authority or overbearing behavior – two complaints and they’re demoted to the ranks. And because income is strictly equal, there are no social classes and few weighty political issues.

One of Bellamy’s most influential critics was William Morris, a romantic counterpart to Bellamy the rationalist. An upper-middle-class background allowed Morris to travel through French Gothic cathedral towns and sojourn among the still pristine architectural beauty of Oxford University, where he imbibed the gospel of medievalism from John Ruskin’s The Stones of Venice. Ruskin found in medieval architecture an ideal of free, creative, self-directed workmanship, sharply different from the hierarchical modern factory and office systems, in which the designer or engineer specifies every aspect of a project and faceless subordinates execute it to the last detail.

Morris thought this stultifying hierarchy would be a necessary consequence of organizing workers into Bellamy’s “industrial army.” Morris’s ideal was the independent craftsman, if possible with more than one string to his (or her) bow. But Morris was a socialist as well as an aesthete, and just as fiercely critical of laissez-faire capitalism as Bellamy, so he undertook to write a portrait of a society that would harmonize solidarity with individuality.

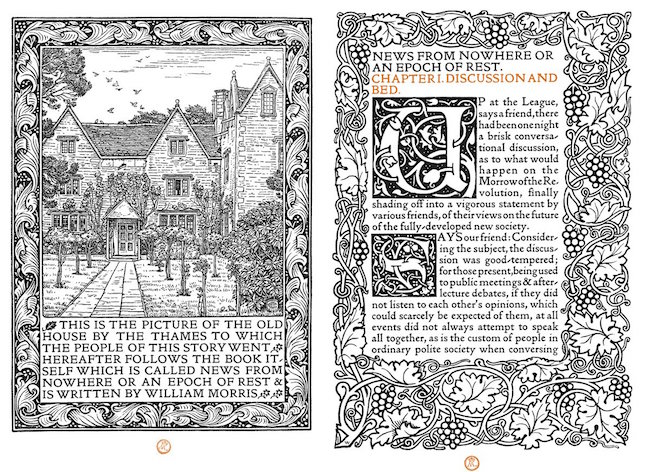

Like Looking Backward, Morris’s News from Nowhere (1890) makes use of a Rip Van Winkle-ish plot device, the protagonist (in this case, a workingman) who falls asleep in the late 19th century and wakes up at the beginning of the 21st. Unlike Julian West, William Guest thinks at first that he’s traveled back in time and awoken in an earlier age, before the blight of industrialism. Instead of the large, splendid modern buildings of Bellamy’s Boston, Morris’s utopia is the “green and pleasant land” celebrated by William Blake, pristine and pastoral, with charming cottages, built to their occupants’ specifications, generally by a party of their friends and neighbors. For the most part, Morris understands progress as the elimination of most of the commercial and technological innovations of the preceding few centuries. No mass production, no railroads, no urban development, no compulsory schooling, and of course (Morris was at bottom an anarchist) no politicians, police, or standing army. The fundamental principle of the society is that work should be pleasure; no useless or tedious work is tolerated, and what is not produced as a result is not missed. Marx wrote, somewhat abstractly, that under communism, “labor is life’s prime want.” Morris, through his village explainer (his equivalent of Dr. Leete), put the same idea more colorfully: “If you are going to ask to be paid for the pleasure of creation, which is what excellence in work means, the next thing we shall hear of will be a bill sent in for the begetting of children.”

Though it’s impossible not to compare Looking Backward with News from Nowhere, it’s not necessary to declare a preference. I have minor reservations about each – there’s something inescapably middle-class about Bellamy’s Boston, while I’m not sure Morris’s rustic idyll is exciting enough for someone who’s bitten into the poisoned apple of modern technology. But both of them are infinitely preferable to America in 2018.

Bellamy and Morris both had many disciples. Looking Backward gave rise to a substantial political movement, called (somewhat unfortunately) Nationalism and incarnated in hundreds of Bellamy Clubs and two journals. One of Nationalism’s adherents, a popular lecturer and contributor to the journals, was the young Charlotte Perkins Gilman. A relative of Harriet Beecher Stowe and other distinguished New Englanders, Gilman had generations of political and religious free thought in her background. Brilliant, beautiful, and passionately committed to sexual and political equality, Gilman might have been one of Henry James’s heroines. Her first love was a woman, who disappointed her by marrying. She then embarked on a long, stormy courtship with a handsome poet. She resisted marrying, but he wore down her defenses. Her husband was unusually enlightened for a 19th-century male, but not nearly enough. She quickly became pregnant, and her feelings of entrapment, culminating in an intense post-partum depression, were the material of “The Yellow Wallpaper.” Gilman eventually rescued herself and obtained a divorce, though it meant relinquishing custody of her daughter for several years.

Gilman wrote several utopian novels and short stories before Herland (1915), her most ambitious production in the genre. Herland, located somewhere in then unmapped South America, is a world without men and therefore without aggression, cruelty, greed, and the other masculine vices, but with all the masculine virtues, which only centuries of oppressive domesticity had prevented women from developing and, of course, a superior technology and culture. Three male explorers stumble on the country, one of them obnoxious and overbearing, one detached and curious, one warmly sympathetic. All three are gradually socialized and return to Ourland, together with several ambassadors from Herland. Herland is a searching, still-relevant critique of sexual politics. As Robertson points out, though, the novel hardly touches on work, economics, or government.

Edward Carpenter is currently the least well-known of Robertson’s subjects, at least in the United States, but he was revered throughout the English-speaking world around the turn of the 20th century. A popular poet, he turned from his early, Tennysonian style to free verse, in imitation of Walt Whitman. His long poem Towards Democracy (1883) was a radical reimagining of industrial society, though not in much detail. The poem sold many thousands of copies, but it might not be remembered today if Carpenter had not been even more famous as a celebrant of homosexual love. He bought a farm and lived there with his lover, a carpenter, while writing discreetly homoerotic verse. E.M. Forster and countless others visited or stayed there, searching for solidarity in what was then still a forbidden love.

Do these “four late nineteenth-century visionaries” still speak to us? Robertson’s claims are modest: “Elements of their transformative visions – environmentalism, economic justice, equality for women and sexual minorities – remain central to progressive politics today.” Dystopias, from 1984 and Brave New World to The Handmaid’s Tale and Hunger Games, have replaced utopian fictions, at least for the time being, but “lived utopianism,” efforts to live out some aspect of an ideal future, from Occupy to Waldorf schools to contemporary food movements, flourish in the society’s interstices.

It is a particularly bleak moment in American history. Neoliberalism is not fascism or Stalinism, but the version administered by the 21st-century Republican Party is a methodical undermining not merely of utopian hopes but of the elementary decencies secured by the New Deal. Civic virtue, trust, and solidarity are increasingly hard to sustain in a Trumpian/Gingrichian world, and the distractions of the online world isolate us for civic purposes as much as they connect us for social purposes. Survival rather than utopia seems like the imperative of tomorrow.

Then again, there’s always the day after tomorrow.

George Scialabba is the author of What Are Intellectuals Good For? and the forthcoming Slouching Toward Utopia, both from Pressed Wafer.