Visual Arts Review: Morgan at the Wadsworth — A Collector of the Fabulous

Nothing of value, it seems, was out of the reach of J. Pierpont Morgan’s acquisitive grasp.

Pierpont Morgan: the Mind of a Collector, at the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford, CT, through December 31.

French, Chasse with Christ in Majesty and the Lamb of God, ca. 1180?90. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Gift of J. Pierpont Morgan, 1917. Photo: Courtesy of the Wadsworth Museum of Art.

By Peter Walsh

“The august Pierpont Morgan,” writes E.L. Doctorow in his 1975 novel, Ragtime, “would routinely consume seven- and eight-course dinners. He ate breakfasts of steaks and chops, eggs, pancakes, broiled fish, rolls and butter, fresh fruit, and cream. The consumption of food was a sacrament of success. A man who carried a great stomach before him was thought to be in his prime.”

The non-fiction Pierpont was just as voracious in his acquisition of art as Doctorow’s fictional character was of late Victorian delicacies. J. Pierpont Morgan: the Mind of a Collector, an exhibition on view at the Wadsworth Athenaeum in Morgan’s home town of Hartford, finds Morgan spending prodigious sums to gobble up collections whole, much as his business trusts swallowed up corporations: $600,000 in 1902 for a private collection of over 1,000 pieces of Chinese porcelain, 161 pieces of Meissen for 17,000 pounds in 1899, European bronzes, Old Master paintings, miniature portraits, Egyptian artifacts, thousands of rare books and manuscripts — more than 20,000 pieces in all by the time he was done.

Nothing of value, it seems, was out of the reach of Morgan’s acquisitive grasp. Visiting Morgan’s London townhouse in 1908, Queen-Empress Alexandra of England and her sister, Dowager Empress Maria Feodorovna of Russia, both daughters of King Christian IX of Denmark, were astonished to see a magnificent suite of French Louis XV period chairs. They had once belonged to their brother, who had been made King George of Greece in 1863. “Why, there are the chairs…,” one of the sisters exclaimed, “our brother had those chairs but they disappeared and we never knew what had become of them; they must have been sold.” Made 150 years earlier by one of the French king’s own furniture makers for a Danish baron and government official, they are now on display in The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

John Pierpont Morgan was born into a prominent and wealthy Hartford family just as that city was growing into a major manufacturing and financial center. Both Morgan and his father, Junius, later worked in the London office of George Peabody, the New England merchant, financier, and pioneer philanthropist. Peabody founded museums with his name at Harvard and Yale and libraries in Baltimore, his native South Danvers (now Peabody), Massachusetts, and in the tiny Vermont village of Thetford, where he had spent part of his childhood with relatives, as well as charitable foundations in both the United States and United Kingdom.

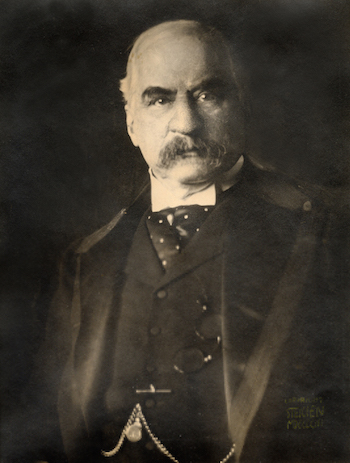

Edward Steichen’s 1903 photographic portrait of Pierpont Morgan. Photo: Courtesy of the Wadsworth Museum of Art.

Junius took over Peabody’s firm after his partner retired (it became J.P. Morgan & Co. after Junius’ death) and some of Peabody’s philanthropy also seems to have rubbed off on the younger Morgan. Pierpont became a major patron of the Wadsworth, where he helped finance a major addition, in memory of his father, that more than doubled the museum’s size. He also lavished his attentions and money on The Metropolitan Museum of Art, where he served as patron, president, and trustee for many years, striving to build it into the great institution it became, and his own, much-cherished library on 36th Street in New York, now a public museum. He was a generous benefactor as well to the American Museum of Natural History, the Groton School, Harvard, and Hartford’s Trinity College among other institutions.

But Pierpont seemed to have regarded his entire career, including his art collecting, as a series of patriotic acts. His Gilded Age financial dealings and his role in the creation of huge trusts, including such monopolistic behemoths as General Electric, United States Steel, and AT&T, were seen at the time as part of the natural evolution of American capitalism, creating greater efficiency, higher profits, good labor relations, and lower prices. His lordly interventions in the national economy— among them his emblematic efforts to calm the Panics of 1893 and 1907— were then widely seen has having saved the country from financial ruin. His heavy-handed moves were his way of bringing the rough and tumble of American business to maturity and stability and making American ventures competitive on a world stage.

At a time when American art museums were almost non-existent, Pierpont also hoped to educate American taste and appreciation of history. He generously lent objects to museums and scholars for study. His will instructed his son, Jack, to distribute his collections “for the instruction and pleasure” of the public. More than 1,350 objects, most of them ancient artifacts or European decorative arts, eventually came to the Wadsworth in 1917. Besides those in The Mind of the Collector, many more are on display in galleries elsewhere in the museum.

True to its title, the Wadsworth show not only samples Morgan’s vast collection but explores the complicated and wide-ranging mind behind it. Morgan was not one of those millionaire collectors who relied mostly on dealers or expert advice for what to buy. His art collection grew directly from the rich soil of his many obsessions and intricate, sometimes even enigmatic, personal agendas.

A consistent theme is Morgan’s fascination with history and, in particular, with royalty. Connections to a crowned owner was a major selling point for him, for example, a plate in the show comes from a Sevres porcelain service Morgan thought (mistakenly, it turns out) had belonged to Catherine the Great of Russia. Another preoccupation is his religious faith. A devout Episcopalian, Morgan assembled a major collection of church papers, and later became an energetic tourist in the Holy Lands, avidly acquiring ancient objects, many related to the emerging field of Biblical archaeology. The selections in the show are mostly small but elegant, like the sleek Ptolemaic-period Egyptian cat that greets visitors at the entrance to the galleries. Other religious objects, including a 14th-century carved ivory tryptic representing the Coronation of the Virgin, are equally introspective, created more for private contemplation than show.

Two large oil paintings, both of them portraits, represent Morgan’s now-dispersed collection of Old Masters. The Wadsworth’s Robert Rich, Second Earl of Warwick, an impressive if somewhat routine Van Dyck, hangs near Goya’s delightful and gently mocking Don Pedro, Duque de Osuna, now in the Frick Collection. But, contradicting Gilded Age stereotypes of vulgar ostentation, most of the 100-plus objects in the exhibition are small and exquisite — finely made, precious objects that inspired the private contemplation of a true connoisseur. There is “The Great Ruby Watch” of ca. 1670, encrusted with delicate enamel and more than 85 jewels, the gilded and enameled “Reliquary of Mary Magdalene,” and “The Morgan Ruby,” a Kangxi-period imperial Chinese vase in the rich glaze known as “oxblood,” said to have belonged to the last Empress. Morgan liked to keep it in his New York library “where he could look at it every day.” There is the 18th-century French “Snuffbox with six scenes of country pastimes,” decorated by two of the leading miniaturists of the late 18th century, and the tiny, vividly painted “Portrait of a Young Man.

Nicholas Hilliard’s 1588 Portrait of a Young Man, Probably Robert Devereux (1566–1601), Second. Photo: Courtesy of the Wadsworth Museum of Art.

Probably the 1588 portrait of Robert Devereux (1566–1601), Second Earl of Essex (cousin and favorite of Elizabeth I), one of eight hundred miniature paintings in Morgan’s collection, is one of the finest in private hands. There is also a Robert Blake drawing, Rembrandt prints,William Morris illustrations, Meissen figurines, and examples from Edward Curtis’ famous photographs of North American Indians, a project the Morgans, father and son, supported to the tune of $400,000.

The Wadsworth installation is elegant and understated, with the deep colors and chiaroscuro Morgan favored in his library. Amongst the art works are scattered personal photographs, a letter from Mark Twain, encoded telegrams from Morgan’s overseas agents, architectural fragments from his houses, a celebrity-studded spread from his London guest book, and other illuminating relics. The extended labels are informative, not only about the objects themselves, but about Morgan himself and the intricate networks of 19th-century art dealers and collectors. They trace the path of objects from collection to collection and to Morgan and then chronicle how son Jack sold off many objects, to Rockefellers and Frick, and finally the holdings of other museums— from which they are reunited for this show.

By the time of his death, in 1913, the same year as the Constitutional amendment establishing the Income Tax was ratified, Morgan’s economic world view seemed deeply dated. Widely attacked as a plutocrat by the Progressives, including his one-time friend, Theodore Roosevelt, Morgan’s carefully constructed industrial organs and huge financial powers no longer seemed beneficial to the nation. Quite the contrary, the left saw him as the evil essence of Gilded Age excess.

In his last years, Pierpont was called before Congressional committees and, after his demise, J.P. Morgan & Co. was split, like an oversized diamond, into fragments which have, however, survived mergers and national downturns to become the JP Morgan Chase and Morgan Stanley of today. Pierpont Morgan remains one of the most ornately ambiguous figures in American history, jeweled bookends of devil and saint. Yet no other patriotic banker stepped in to save America in 1929 and 2008. And no wealthy art collector, probably, has so richly endowed the American public with fine art.

Peter Walsh has worked as a staff member or consultant to such museums as the Harvard Art Museums, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, the Davis Museum at Wellesley College, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, the National Gallery of Art, and the Boston Athenaeum. As an art historian and media scholar, he has lectured in Boston, New York, Chicago, Toronto, San Francisco, London, and Milan, among other cities and has presented papers at MIT eight times. He has published in American and European newspapers, journals, and in anthologies. In recent years, he began a career as an actor and has since worked on more than eighty projects, including theater, national television, and such award-winning films as Spotlight, The Second Life, and Brute Sanity. He is a graduate of Oberlin College and Harvard University.

Fascinating portrait of such an enigmatic titan. ] That he accomplished so much in a lifetime is extraordinary. The Legacy of this Renaissance man enriches art and life all around us.