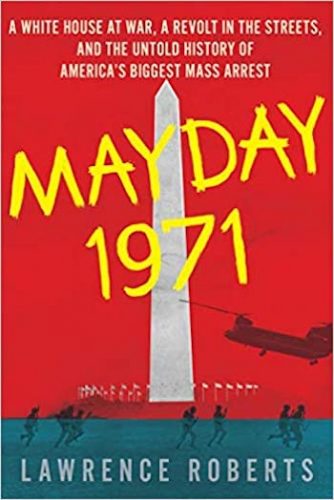

Book Feature: Children of the Revolution — An Interview with Lawrence Roberts about Mayday 1971

By David Stewart

“One lesson is that when a country feels like it’s really gone off on the wrong track, a social movement that finds a way to express that dissent in the streets can really make a difference.”

On June 1st, President Trump ordered the US Park Police, Customs and Border Patrol, and the National Guard to teargas Black Lives Matter protestors in Lafayette Park before posing outside of St. John’s Church for a photo op. For the Twitter generation, the past year has been traumatic: videos of unidentified agents macing and arresting protestors in Portland, Oregon, and Chicago have been circulating around the web. This mayhem is nothing new for those who grew up during the Civil Rights movement and marched in opposition to the Vietnam War. It is déjà vu all over again, a revival of the social dissent that erupted half a century ago when hundreds of thousands of young Americans flocked to the streets and National Mall in Washington, DC, to shut down the nation’s capital and pressure Richard Nixon to end the war. Veteran journalist Lawrence Roberts takes us back to the future in his first book, Mayday 1971: A White House at War, A Revolt in the Streets, and the Untold History of America’s Biggest Mass Arrest (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 448 pages, $28), which covers the actions taken by the Nixon Administration, the DC Police, the courts, and the activists.

On June 1st, President Trump ordered the US Park Police, Customs and Border Patrol, and the National Guard to teargas Black Lives Matter protestors in Lafayette Park before posing outside of St. John’s Church for a photo op. For the Twitter generation, the past year has been traumatic: videos of unidentified agents macing and arresting protestors in Portland, Oregon, and Chicago have been circulating around the web. This mayhem is nothing new for those who grew up during the Civil Rights movement and marched in opposition to the Vietnam War. It is déjà vu all over again, a revival of the social dissent that erupted half a century ago when hundreds of thousands of young Americans flocked to the streets and National Mall in Washington, DC, to shut down the nation’s capital and pressure Richard Nixon to end the war. Veteran journalist Lawrence Roberts takes us back to the future in his first book, Mayday 1971: A White House at War, A Revolt in the Streets, and the Untold History of America’s Biggest Mass Arrest (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 448 pages, $28), which covers the actions taken by the Nixon Administration, the DC Police, the courts, and the activists.

Long before working as an investigations editor at The Washington Post, helping to lead the Pulitzer Prize–winning teams that covered Dick Cheney’s vice presidency and the Jack Abramoff lobbying scandal, Roberts was a college student who witnessed the protests and the heavy-handed police efforts that led to the arrest or detention of 12,000 people in the nation’s capital. However, Roberts asserts that his book is not a memoir, but an in-depth look at the key figures in the Spring Offensive. “I was a foot-soldier. I wasn’t any kind of leader in the movement.” Roberts said from his home outside Washington. “My interest was to bring my journalistic sensibilities to that time, and not be too influenced by what I personally saw back then.”

Decades before iPhones and body cameras, the DC police had Polaroid Swingers dangling from their necks as they photographed and arrested protestors and innocent bystanders that May 1971 weekend. The activists, angered by the shootings at Kent State and fearful of being drafted to serve in a war they didn’t believe in, used walkie-talkies and mimeograph machines to publish leaflets and newsletters. As he was researching the book, Roberts was surprised by how the word got out among the protesters: “You had mimeograph machines and you had to use the telephone and a lot of these organizers who worked at the central office where the antiwar movement was in ’71, they were literally writing letters to their chapters in Milwaukee and all these other places and waiting for the mail to come back to figure out what was going to happen, yet you still had hundreds of thousands of people showing up. It’s kind of remarkable.”

Not only was the Spring Offensive a call-to-arms for those who opposed the Nixon Administration and his military tactics in Southeast Asia, but it was a chance for the White House to retaliate by rounding up those that might have been associated with the bombing of the US Capitol in March 1971. The Weather Underground, the militant offshoot of the SDS (Students for a Democratic Society), claimed responsibility for planting the bomb. Jerry Wilson, the DC police chief, had ambitions to bring reform and racial equality in the police force, but his ideas were overlooked by his superiors. Roberts found Wilson to be a man of integrity forced to make some difficult choices when faced with Nixon’s authoritarian demands. He ended up doing what he was told, but not without some regrets. “Wilson grew up in small-town North Carolina. His father was a mill worker, the town was full of textile mills, that’s all there was. There were these huge labor battles in the thirties; his father slept with a shotgun under his bed, yet he came out of it, enlists in the Navy when he’s 14 to fight in WWII, but he comes out of it with a native wisdom about things. It’s hard to see out of the environment that you are coming from, but he was able to do and see that. Some of the things that he talks about regarding police reform back then are still being talked about today. He tried to change the situation: he was an outsider and, as with everybody, some of your character flaws end up undermining you in the end and I think that he had this serious desire to be promoted to the head of the FBI.”

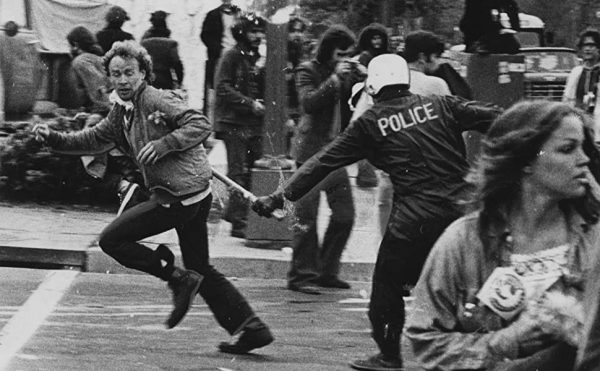

Protesters taking part in one of the May Day rallies in early May, 1971. Photo credit: Star Collection, DC Public Library; © Washington Post. Wiki Commons.

Predictably, Nixon comes off as an enigma in May 1971. He was desperate to be liked; the press noted that he had his assistant’s dog on his lap before he flew off to Camp David (no doubt inspired by his infamous Checkers speech during his tenure as vice president under Eisenhower). After spending hours listening to Nixon’s tapes at the National Archive, Roberts thinks his need for public approval was Nixon’s tragic flaw: “There’s a desperation to be loved that all politicians share. But for Nixon, I think that desperation was really the cause of his downfall. His high intelligence and his astonishing work ethic were the things that made him triumph as a politician, but he never could lose that feeling of ‘what do they think of me?’ He wanted to be thought of like Jack Kennedy or somebody like that. He wanted his triumphs to be celebrated; he didn’t want people talking about his awkwardness or challenging his vision. Whatever you might think of his vision for the country, he had one, and he tried to implement it. He had a deep understanding of the world and politics, certainly more so than the current president. But his character flaws overcame his genuine achievements. If it hadn’t been Watergate, it would have been something else that would undo him and lead to his downfall.”

It’s difficult not to compare Nixon’s and Donald Trump’s vitriolic attitudes toward dissent and their embrace of law-and-order. Roberts has thought long and hard about the two’s treatment of dissent: “Trump has been carrying out some practices that Nixon carried out. But there are a lot of key differences between them. Nixon was a learned man, he was a reader of history. He was also ruthless, but he made his most ruthless comments in private and ordered his most unconstitutional actions in private and tried to cover them up. The current president doesn’t seem to have any desire to cover up either his most base instincts or his acts that are of questionable constitutionality.” Roberts argues that the inevitable Nixon/Trump comparisons only go so far, though it is a fascinating contrast, given how both men riled up the not-so-silent majority. “Certainly, the use of violence as a political weapon, or complaining about alleged violence by protestors as a political weapon, is something that the two men share.”

Yippie activists Abbie Hoffman and Jerry Rubin have been lionized by counterculture historians since their comedic/political actions at the Chicago Democratic Convention in 1968. (Among their antics — bringing a pig as presidential nominee and throwing dollar bills from the New York Stock Exchange a year earlier). But the actions of Stew Albert and Judy Gumbo intrigued Roberts more than the media-prone Hoffman and Rubin. “I think Rosencrantz and Guildenstern characters are often better vehicles for telling a history,” Roberts explained “The Yippies were interesting- — Stew Albert and Judy Gumbo who were the Yippie founders — because they were part of the Capitol Bombing investigation as well as Chicago in ’68 as well as Mayday and the FBI surveillance. By examining them, you could have an interesting way to look at the times. They struck me as fresher sets of eyes to be used to retell the story than Abbie Hoffman and Jerry Rubin, who have been written about quite a bit and were more creations of the media.

Violence on the streets of Washington, DC, nearly 60 years ago. Photo (c) 1971 by Douglas Chevalier/Washington Post/Amazon.com

Fifty years after the turmoil of Vietnam and the social strife endured by the counterculture movement, Roberts hopes his book will be seen as just another case study of what happens when American politics and public dissent collide. “I think that as I went into this,” Roberts recalled, “I was trying to explain or recreate the tensions of a very volatile time in America where it turns out that we had an embattled president facing a social movement in the streets and where institutions seemed to be losing their footing and people weren’t sure what the future was going to hold. Ultimately, the justice system and some heroic people got us through it. The republic survived and people who had crossed the line got their just desserts, so I think it’s an object lesson. There is something very resilient about American democracy and American justice, so let’s put our faith in that again — that we will come out of this crazy time in a place where we can move forward again. I hope people take that lesson, as well as the lesson that when a country feels like it’s really gone off on the wrong track, a social movement that finds a way to express that dissent in the streets can really make a difference.”

David Stewart is a Professor of Film and Media Studies at Plymouth State University. Along with teaching, he is a documentary researcher and contributing writer for PleaseKillMe.com and DMovies.org. His film credits include Amy Scott’s documentary Hal and Marielle Heller’s The Diary of a Teenage Girl. He lives outside of Boston with his family and beloved Fender acoustic, Nadine.

I was there then and I’m here now and, as Roberts says, there are definitely parallels. However, there was nothing comparable then to the agglutination of foul energy called QAnon. Does the author see this as representing a real threat to the resilience of “American democracy and American justice”? If not, I’d find his thesis questionable.

Fair question, but important to note that right-wing conspiracy groups have always been with us. The network in the 1970s most analogous to QAnon might have been a group calling itself Posse Comitatus. See Daniel Levitas on that history: https://www.nytimes.com/2002/11/17/books/chapters/the-terrorist-next-door.html

Yes, there certainly have always been right-wing conspiracy groups and there’s a link, of course, between the Posse Comitatus and QAnon. But the differences are so great as to keep my question in play.

First, although there were guys in pick up trucks cracking the heads of hippies during the era of mass demonstrations, the Posse was in early stages and far from a national movement. Second, Nixon and co., as bad as they were, did not abet these movements the way the Trump mafia does. Third-social media-the most effective means of spreading barbarity and hate we humans have yet managed to develop.