Visual Arts Review: A Joyous Look at New American Sculpture, 1914 – 1945

These are men who appreciated women for their bodies, athleticism, motherhood, intelligence, and humor – all reasons to celebrate this show.

A New American Sculpture, 1914 – 1945 at the Portland Museum of Art, Portland, Maine, through September 8, 2017

Robert Laurent,”Hero and Leander,” circa 1943. Photo: Bruce Schwarz.

By Kathleen Stone

Joy. That’s what I felt as I entered the sculpture show at the Portland Museum of Art. There were bodies dancing, leaping, stretching, caressing, and floating through space. My delight never let up, lasting until the final sight — a monumental bronze woman, on her toes with arms raised. She seemed to be lifting herself off the ground.

The four sculptors – Gaston Lachaise, Robert Laurent, Elie Nadelman, and William Zorach – are linked by circumstance: born in Europe, students in Paris, and immigrants to the United States. In the decades between the First and Second World Wars, they assumed the position of preeminent American sculptors, largely responsible for defining what modernism in three dimensions looked like on these shores.

What they encountered in Paris was not exactly stodgy. Auguste Rodin had already shaken up the establishment with his dramatically expressive figures; Aristide Maillol, Wilhelm Lehmbruck, and others were updating classical forms; and painters such as Picasso and Matisse were studying the art of other cultures — often African and Oceanic — for inspiration. Educating themselves through visits to studios and exhibitions, the young sculptors immersed themselves in the revolutionary work around them and came to share the aesthetic goal of infusing natural forms with innovative ideas and techniques.

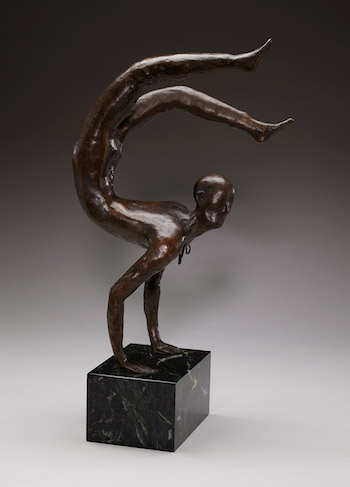

Elie Nadelman, “Acrobat,” 1916. Photo: Bruce Schwarz.

Nadelman, for instance, distilled form to simple, elegant lines. His claim that Picasso stole the idea of cubism from him, after Leo Stein brought Pablo to his studio, may have some truth to it – a Nadelman drawing from 1906 shows a clear cubist impulse – but he did not exploit it as rapidly or as deeply as Picasso. And Nadelman continued working in other veins. Acrobat, his bronze from 1916, shows a man balancing on his hands, arching his back. It’s an athletic feat, but there’s whimsy, too – the bow tie hanging from the acrobat’s neck provides a light, humanizing touch.

After Nadelman settled in New York, he began scouring the countryside for folk art. The collecting trips paid off: sculptures from this period depict people enjoying popular entertainment – a couple dancing the tango, a conductor raising his arm to the orchestra, a dancer kicking her leg high. The pieces make affecting use of the simplified form and wood material common to folk art. But his oeuvre was broader than that; one of my favorite Nadelman pieces is The Hostess, a bronze. The woman’s arms and legs are tapered in his trademark style — she wears a close fitting cocktail dress and heels. He has caught her right in the middle of a party, as if she is about to say (perhaps): “May I offer you another drink?” There is a persistent (and welcome) sense of light-hearted fun in Nadelman’s work, but he was a serious artist on par with his compatriots.

Like Nadelman, Laurent studied classical sculpture but he grew well past it. He was among the first to introduce African aesthetics to American art. Even before Alfred Stieglitz exhibited African sculpture at his New York gallery in 1915, Laurent was exploring ideas about volume, body, and expressiveness derived from African art, as well as from the folk art of his native Brittany. Laurent discovered abstraction early on (his wood carving Head, from 1916, is an example), but he never entirely let go of his feel for the classical. Several of his alabaster pieces here are extraordinary: carved into undulating forms, the material gives off an otherworldly sheen. In The Wave, a woman is surrounded by swirling liquid, her arms and legs curled beneath her — a neo-classical heroine the act of surrender. In The Bather, Laurent reprises the ever-popular subject of a woman at her bath; her alabaster hair cascades to her knees as though it is made of water. Technically impressive, sensuous in form, these are gorgeous works.

In a wood carving from 1940 Laurent deftly combines his modern vision with a classical theme. The nymph Daphne is transforming herself into a laurel tree, the ploy she uses to escape the unwanted advances of Apollo. The sculpture is a single, elongated shape, with her hands stretched overhead, leaves sprouting from her hair. Apollo’s hand grasps her leg. Compare this to Bernini’s marble from three hundred years earlier and you will appreciate the cool, contemporary spirit Laurent brings to the subject.

Zorach, born in Lithuania, spent his childhood in Cleveland and went to Paris as a young man, where he met the painter Marguerite Thompson. They married, exhibited in the 1913 Armory Show, had two children, and began to make places for themselves in the art world of New York just as it was beginning its ascendancy.

At first, Zorach was tentative regarding sculpture, but he came to prefer it to painting. He often uses family groupings and individuals as subjects. Most of his women are not identified, but Marguerite must have been his most frequent model – his female figures are usually marked by the distinctive features, clear intellect, and strong will I have seen in photographs of Marguerite. For younger women and girls, he often used his daughter Dahlov as a model. Several years ago I interviewed Dahlov, and I asked her why she decided to marry a man who had once worked as an accountant. “I didn’t want to marry an artist,” she responded. “I was afraid I would just become his model and I was sick of posing!” Seeing her father’s work in this show, I understand what she meant. There’s Dahlov (1920), The Artists Daughter (1930), Kiddy Kar (1930), Child on a Pony (1934), and Bathing Girl (1934) – she is there in all of them.

Zorach, “Mother and Child,” 1922. Photo: Bruce Schwarz.

As much as family was a mainstay of his work, Zorach tackled other subjects in a variety of materials – Head of Christ in stone, Floating Figure in mahogany, Family Group in aluminum, Spirit of the Dance in bronze. This last one merits particular mention. It shows a tall, slender woman on one knee, turning her torso. She is over six feet tall, even kneeling, and so graceful as to be the epitome of dance. Mother and Child is another Zorach showstopper, a carving in mahogany. The mother holds a young child, her face buried in her baby’s neck. We can’t tell if Marguerite was the model, but the feeling of intimacy and love is so profound that it’s easy to imagine Zorach was expressing the passionate bonds of his family.

Lachaise was a prolific sculptor who often worked in bronze and aluminum. Isabel Nagle, his muse and wife, had a substantial figure — orb-like breasts, a round belly, and strong legs. Incredibly, though, Lachaise portrays her as so light on her feet that she seems barely tethered to the ground. In one of the most arresting pieces in the exhibition, Passion, he gives us two lovers embracing. The woman has considerable heft, but she seems so ethereal that the man lifts her effortlessly as she wraps a leg around his.

Lachaise, too, has an Acrobat, but unlike Nadelman’s the figure is neither slender nor whimsical. It’s a large limbed woman, who, incredibly, is caught in the act of balancing on her shoulder. We see Nagle again and again in Lachaise’s work – tiptoeing up a step, standing on the back of a male acrobat, perching astride a horse and, finally, in the last gallery, as the well-known Standing Woman, where she lifts her heels and raises her arms — the vision of a buoyant goddess.

Women were not the only subject for these sculptors, but females were depicted often. From all appearances, these men loved women. They celebrated the female form in many guises – lover, mother, acrobat, dancer, bather, nymph, and hostess. Sometimes the body is sensual, but the treatment is never exploitative. These are men who appreciated women for their bodies, athleticism, motherhood, intelligence, and humor — all reasons to celebrate this show.

Kathleen Stone lives in Boston and writes critical reviews for The Arts Fuse. She co-hosts a literary salon known as Booklab and is at work on several long projects. She holds graduate degrees from the Bennington Writing Seminars and Boston University School of Law, and her blog can be found here.

Tagged: A New American Sculpture, Elie Nadelman, Gaston Lachaise, Kathleen Stone, Portland Museum of Art, Robert Laurent