Rethinking the Repertoire #14 – Sir Edward Elgar’s “Sea Pictures”

It is one of the enduring ironies of classical music that so much of today’s repertoire was written by such a small number of people. This post is the fourteenth in a multipart Arts Fuse series dedicated to reevaluating neglected and overlooked orchestral music. Comments and suggestions are welcome at the bottom of the page or to jonathanblumhofer@artsfuse.org.

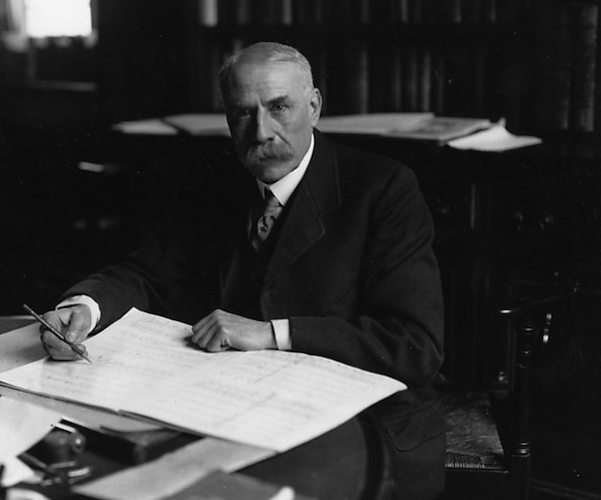

Edward Elgar — unfairly, at his death, the composer was viewed as a total anachronism.

By Jonathan Blumhofer

Timing may not be everything, but it sure counts for a lot. Take Edward Elgar. The British composer triumphed rather late in life: he was forty-two when the Enigma Variations finally established him as a major figure on the European scene in 1899. His window for opportunity, though, was a surprisingly small one. Within a little more than twenty years, his music – hailed in 1902 by Richard Strauss as “the first English progressivist” and representative of “the young progressivist school of English composers” – was seen as almost hopelessly out-of-date, the victim of a world and musical aesthetics turned upside by World War 1.

At his death in 1934, Elgar, the perennial outsider, was viewed as a total anachronism, a throwback to the golden, irretrievable days of Edward VII. And his posthumous reputation wasn’t improved by the ascendance of a younger generation more in tune with the times, led by Benjamin Britten and William Walton.

A shift in attitudes came gradually, most strongly in the British Isles, by the 1960s. And, of course, Elgar was never really out of the public eye during that time or since. Certain works – the Enigma Variations, one or two of the Pomp and Circumstance marches, and the Violin and Cello Concertos – have managed a certain enduring staying power. His oratorio, The Dream of Gerontius, has done the same and you’ll occasionally come across presentations of one of his other big, sacred choral score, The Apostles.

But despite this, and even if his standing has improved in the last fifty or so years, Elgar’s wider catalogue has had a hard time finding an abiding footing outside of England. That’s especially surprising, considering that many of his finest champions haven’t been English-born. Additionally, conductors like Georg Solti, Andre Previn, and Daniel Barenboim have held prominent American posts. Whatever successes marked their careers, building trans-continental enthusiasm for Elgar hasn’t been one of them.

So what have we been missing? Well, there is quite a bit of music, some of it small. The Wand of Youth suites, the Three Bavarian Dances, Sospiri, among them, are winning pieces and charming. Bigger works, like In the South and the Introduction and Allegro remain largely curiosities.

More significantly, Elgar’s two symphonies are, if not unknown, then at least extremely rare to come across on these shores. Each is a masterpiece of the first rank. The first follows an arduous journey from doubt and trial to unalloyed triumph; its finale features some of the most stirring music written in the whole twentieth century.

Elgar’s Second is more enigmatic. But, if anything, it’s an even more striking piece than the First. Mournful and elegiac the music often is, but the writing is so turbulent, so beautiful, so inventive, and – above all – so personal, as to be unforgettable. Its high point is the majestic second movement, on its surface a memorial ode to the recently-deceased Edward VII that is somehow so much more: at its climax, the violins intone a weeping figure that smears the lament’s makeup in a totally unexpected, un-Imperial display of naked emotion. Why this music isn’t programmed with the frequency and devotion of the Mahler symphonies is a puzzle.

The same goes for Sea Pictures, Elgar’s 1899 song cycle of poems by five authors, including his wife, Caroline. Composed just after the Enigma Variations, Sea Pictures focuses on what Fred Kirschnit calls the “overwhelming attraction of oblivion,” the shadowy appeal of death as represented by (and realized in) the immeasurability of the sea.

But it’s hardly grim stuff. The first movement, “Sea Slumber-Song,” is just that: a gentle lullaby, marked in the orchestral writing by a rocking, wave-like arpeggio figure that opens the piece. There are a few episodes of text painting – the glittering harp writing at the line “On this elfin land” being a prominent one – but, mostly, this song follows an ABAB structure, with a slightly varied A1 section and a surprising turn to the minor at the very end.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sEDHaJ1mn5M

The second, “In Haven (Capri),” is even more straightforward. Setting his wife, Caroline’s, text, it’s a simple, strophic song marked by the lapping of steady, low-string arpeggios and a gentle, breeze-like figure that’s passed around the orchestra’s upper voices. The vocal line is a lilting, often triadic, diatonic tune.

In the third song, a setting of Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s “Sabbath Morning at Sea,” the writing is more involved, motivically. It opens with a vocal “quasi recitative,” underneath which the accompaniment from “Sea Slumber-Song’s” B-section reappears. This gives way pretty quickly to an in-tempo passage that builds to a stately, “molto maestoso,” of the kind Elgar was so adept at crafting. Then, on the line “Love me, dear friends, this Sabbath day,” the scoring lightens, and the music sort of floats along, led by a solo violin. The quasi recitative bit and the latter theme are repeated, though the last is now takes on the character of the “molto maestoso” interlude. It’s ultimately expanded to incorporate the wave-like arpeggios of the first movement, resolving, this time, in the major mode.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xh0BJmhzT1A

Sea Pictures’ fourth movement sets Richard Garnett’s “Where Corals Lie.” Like in “In Haven,” the writing is gentle and largely pastoral, Elgar opting for a strophic setting of three of the poem’s four stanzas. His approach to each verse is slightly varied – similar to what Mahler was doing around the same time in his Gesellen– and Rückert-Lieder – with a subtle variation to the scoring for each strophe.

For the finale, a setting of Adam Lindsay Gordon’s “The Swimmer,” Elgar’s painterly palette conjures up everything from storm-tossed whitecaps to the serene majesty of an open seascape. Of particular significance is a stately, triadic refrain that neatly suggests the land of Hope and Glory of the Pomp and Circumstance marches. The vocal line, which itself recalls a number of ideas heard earlier, here sometimes cedes way and gives the orchestra the melodic lead.

Since its premiere at the Norwich Festival in October 1899 (at which contralto Clara Butt appeared dressed as a mermaid), Sea Pictures made its rounds and then, outside of Europe, largely disappeared.The last time the Boston Symphony played it was in 1911. The only time the New York Philharmonic performed it in full was in 1980 (and their prior performance of excerpts was with Mahler on the podium, just a week before his final concert in 1911). Why is this the case?

No one reason perfectly suffices. Yes, the piece has been dogged by complaints about the unevenness of its texts. But the music largely overcomes them. And, on top of that, Elgar wasn’t the only composer of the day utilizing workaday poems: Mahler and Berg, among others, did much the same over the 1890s and 1900s, and Elgar’s writing here is on par with both of theirs.

It seems that the biggest obstacle to Sea Pictures’ wider acceptance is the stubborn durability of the image of Elgar as, in the words of Tom Service

a composer who could be encapsulated by the clichés of the Last Night of the Proms and his handlebar moustache, [a figure] mired in a British backwater of fusty romanticism that was outdated even in its own time, and doomed forever only to speak of ludicrous Imperial ambition and patriotic stiff upper lips.

For Service, it was the Second Symphony that helped rid him of what he called “the idiocy of my thinking about Elgar”; what will it take for everyone else? Perhaps the same – or hearing Sea Pictures with open ear. It offers, frankly, everything one might want in a song cycle: sweeping melodies, evocative scoring, stirring drama and pathos, and – that requisite Elgar ingredient – lots of heart.

Jonathan Blumhofer is a composer and violist who has been active in the greater Boston area since 2004. His music has received numerous awards and been performed by various ensembles, including the American Composers Orchestra, Kiev Philharmonic, Camerata Chicago, Xanthos Ensemble, and Juventas New Music Group. Since receiving his doctorate from Boston University in 2010, Jon has taught at Clark University, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and online for the University of Phoenix, in addition to writing music criticism for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette.

Thank you so much for this. What a glorious work!

If I may toot my own horn, I refer you to my Arts on Stamps of the World piece (right here on the Arts Fuse) for yesterday, June 2nd, Elgar’s birthday, which includes a stamp specifically citing the great Sea Pictures.

Excellent article. Listening to Janet Baker singing it as I write. Haven’t played this for ages but can’t get the tunes out of my head since I ‘rediscovered’ it in my LP collection the other day. It’s not been off my turntable since. As you say, it’s surprisingly varied and… well just glorious.

Tim