Theater Review: “Kunstler” — A Radical for the Defense

Barrington Stage has kicked off its summer season with a smart, funny, and very timely show about radical defense attorney William Kunstler.

Kunstler by Jeffrey Sweet. Directed by Meagen Fay. Staged by the Barrington Stage Company in the St. Germain Stage, Pittsfield, MA, through June 10.

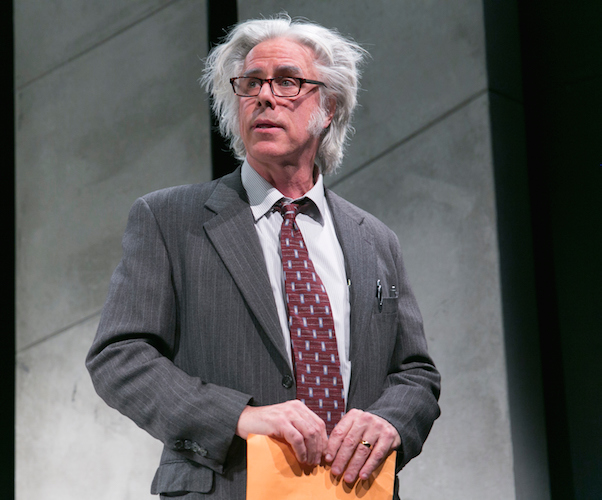

Jeff McCarthy as William Kunstler in the Barrington Stage Company production of “Kunstler.” Photo: Carol Rosegg.

By Helen Epstein

On a day when Vice President Mike Pence’s commencement speech was boycotted and booed at Notre Dame University, Barrington Stage kicked off its summer season with a smart, funny, and very timely show about radical defense attorney William Kunstler (1919-1995).

Playwright Jeffrey Sweet was watching a documentary about Kunstler a few years ago when he was struck by Kunstler’s resemblance to his friend Jeff McCarthy, long-time Barrington Stage actor and memorable Man of La Mancha. A teenager in Chicago during the 1960s, Sweet was also intrigued by the spectacle of a man who had remained the same, even after times had changed. He wrote the part for McCarthy, who brought it to the Pittsfield Theater in 2013 and developed the role with Sweet and director Meagen Fay at the Hudson Stage, the 59E59 Theater, and The Creative Place International/AND Theater Company.

The result is an upbeat and highly entertaining two-hander, with a superb script, a virtuoso turn by McCarthy, and a strong supporting performance by Erin Roché as Kerry Nicholas, the African-American law student who is Kunstler’s sometimes agonized, sometimes unwillingly impressed, interlocutor.

The play is set in 1995, the Clinton era, and takes place at what had already become a common and awkward campus situation. Guest speaker William Kunstler, a bit creaky but still ebullient at 75, walks through a crowd of protesters outside of the theater (suggested by the sound design) into the lecture hall at a prominent law school. The stage is strewn with garbage; a scarecrow-like effigy of Kunstler with the sign “Traitor” around his neck hangs in front of the podium. Twenty-something Kerry, Vice-Chair of the Program Committee, is trying to clean up before the lecture. She cuts down the caricature and tries to stuff it into a trash can while welcoming Kunstler.

It’s clear that law student Kerry (a role Sweet specified as African-American) shares the sentiments of the orange-colored “Boycott” fliers that BSC theatergoers find on their seats. The fliers accuse Kunstler of being “a sellout and a hypocrite,” whose “defence of Traiters; Terrorists; and Rapists is an insult to the causes for what which he once stood.” (Sic)

When Kerry asks Kunstler if there’s anything particular he’d like her to include in her introduction, he indicates the language of those fliers. He suggests that he prefers newspaper insults like “The lawyer for causes of which none is more unpopular than he — that was in the Washington Post. And someone in the New York Times called me a schlemiel with an edge. You know what a schlemiel is?”

Kerry does not know the answer and, in explaining the Yiddish term, Sweet introduces one of the sub-themes of Kunstler: the shift in the relationship between African-Americans and American Jews, who began as partners in the civil rights movement of the early 1960s and saw themselves pushed to the sidelines.

Another sub-theme of what can be viewed as this mini-law lesson explores has changed and what remains the same between the law students of today and those of the 1990s. How have race, gender, and ethnicity affected those changes? What are the rules regarding routine verbal and physical interactions between men and women? And what resonances does “rule of law” have in 2017?

Diplomatically, Vice-Chair Kerry decides to introduce Kunstler as one of a handful of people who need no introduction: “Those of us here who are law students, we’re familiar with many of his cases… he is one of the more controversial figures of our time. I think it’s safe to say that he doesn’t mind being identified as such. So please welcome William Kunstler.”

Kunstler, who is visibly suffering from the cardiac condition that ended his life a few months after the play is set, steps up to the podium. He leads off with lawyer jokes, then segues into the story of his career, with an emphasis on initial idealistic phase, as a crusader for civil rights and justice. What keeps Kunstler from the tumbling into the pitfalls of the one-man show (a gabby monologue) is the give-and-take that Sweet develops between the its protagonist and the Vice Chair of the Program Committee. The grandstanding Kunstler, alternately beguiling and bullying, goes to considerable lengths to justify himself and his professional choices to the prim, young, and critical Kerry. They maintain an unusual, but credible and lively connection, that keeps changing as they interact and clash over issues seen through the prisms of age, race, gender, identity politics, and changing expectations.

“It may surprise you to know I did have a life before “the law,” recalls Kunstler at the beginning of his address to the students. The character goes back to his service in the second world war, then to law school and 12 years of a comfortable postwar life in a suburb of New York City. Then, in 1961, he’s asked by the ACLU to fly to Jackson, Mississippi where the Freedom Riders — “you’ve probably heard the term” Kunstler tells the audience — have begun to desegregate lunch counters.

Mississippi was, in Kunstler’s telling of it, where he understood that his work as a defense attorney was not going to be about service of some abstract ideal, but a means to support the political objectives of his clients, which came to include the Berrigan brothers and the Chicago Seven — Jerry Rubin, Tom Hayden, Rennie Davis, David Dellinger, Abbie Hoffman, John R. Froines and Lee Weiner — who were charged with conspiracy to incite riots at the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago. Kunstler also talks about his defense of members of the Black Panther Party, Attica Prison rioters, and the American Indian Movement.

Kunstler concludes what is in essence a defense of his brilliant career at what Kerry considers the high point. She accords him the customary thank yous, but Sweet does not end the play there. Instead, he has Kunstler prod Kerry into saying what’s really on her mind and she declares her disappointment in him to him: To go from defending the Chicago Seven, the Berrigans and the victims of Wounded Knee to defending criminals such as mobster John Gotti and Yusef Salaam, the alleged Central Park rapist and Colin Ferguson, who killed six people on the Long Island Railroad! And to be photographed hugging them!

Director Meagen Fay keeps what might have become a boring 35-year history lesson lively without the help of any slides, photographs, or other visual aids. The often complicated narrative remains clear and compelling, even to someone, like my French husband, who is unfamiliar with many of the names and movements of recent 20th century American history that are referenced. Fay’s choice to keep an uncluttered and close focus on Sweet’s sharply articulated dialogue pays off in terms of dramatic intelligibility, heightening our insight into Kunstler and Kerry’s characters and their evolving relationship. Still, I found myself wishing that a more innovative way to visually evoke the history and atmosphere has been found. Archival photographs of Kunstler, his clients, and the dramatis personae of their times would have helped considerably, as well as newspaper headlines or TV footage. The erratic — sometimes corny/perhaps meant to be ironic — sound design did not do the job.

But Kunstler is a stimulating theatrical vehicle rather than a history play. Jeff McCarthy supplies a tour de force performance playing, what is for him, a perfect role. He becomes the reincarnation of Kunstler in our minds, if more likable and engaging than the original. Not only is the actor given a chance to flex all his performing chops, but the play provides the occasion for an auspicious BSC debut for Erin Roché, cast in a rare role on stage: a black woman who is realistically and meaningfully given an opportunity to challenge a privileged white man.

Helen Epstein is the author, co-author, editor or translator of ten books of non-fiction. She e-publishes classics of non-fiction with Patrick Mehr here.

Tagged: Barrington Stage Company, Culture Vulture, Kunstler, Meagen Fay

No one should forget that Yusef Salaam was exonerated.