Book Review: “Eve out of her Ruins” — Mauritian Realities

It would be a mistake to call the absorbing Eve out of her Ruins a mystery novel or even a novel exclusively devoted to social realities.

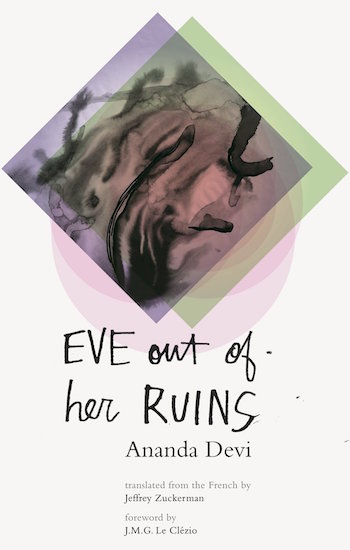

Eve out of her Ruins, by Ananda Devi, translated by Jeffrey Zuckerman, with a foreword by J.M.G. Le Clézio, Deep Vellum, 145 pp., $14.95.

By John Taylor

Born in 1957 in Mauritius, Ananda Devi uses her native island as the setting of her absorbing novel, Eve out of her Ruins. First published in France as Ève de ses décombres (2006) and now resourcefully translated by Jeffrey Zuckerman, the novel deals with the violent, sordid side of this island located in the Indian Ocean.

The story is woven from a series of monologues. Each new short chapter is spoken in turn by one of four characters in their late-teens: Eve, who prostitutes herself in order to pay for her schooling; Saad, a Rimbaud-loving good student by day and gang member by night, who is in love with Eve; Clélio, a full-fledged gang member who knows that he is heading down the wrong path and hopes that his brother, an immigrant in France, will send for him; and Savita, a classmate of Eve’s who also loves her. The first love scene between Eve and Savita is especially striking. It is Eve who remembers this initial, initiatory encounter:

She wiped my brow. Then she leaned over and kissed me.

The taste of her mouth wasn’t at all like those of men. It was so gentle that I closed my eyes and savored it like candied papaya. I inhaled it deep into my mouth.

Outside the purview of men, we became happy, playful, for a few minutes. A warm perfume wafted from her navel. We teetered on tiptoes. It was so strange. We were smiling like drowned souls finally at peace. We danced on a tightrope that stretched from her heart to mine.

Such tenderness crops up a few other times in this novel, within a reality that could not be further removed from sandy beaches and gentle ocean breezes.

The lives of these soul-searching characters intersect in Troumaron, a neighborhood which, as Saad phrases it, is “a gray place […] or rather, yellowish brown […] a sort of funnel where all the island’s wastewaters ultimately flow.” The place name literally means “brown hole,” with obvious metaphorical connotations. In his Translator’s Afterword, Zuckerman points out other multilingual puns running through the novel. Because of its Dutch, French, and English colonial background, most inhabitants of Mauritius speak English, French, and Mauritian Creole fluently.

Moreover, the island was and continues to be populated by settlers and immigrants, including slaves and indentured servants, from Western Europe, East Africa, India, and China. With the partial exception of Savita, the four characters are going astray in this multilingual melting pot, although they attend school—a positive factor in a rough urban environment that offers few redeeming possibilities. They mostly lead their lives away from home and parents, and get into trouble.

In his foreword, the Nobel-prizewinning French novelist J. M. G. Le Clézio, who has family connections with Mauritius, depicts “an island of violence and promiscuity, where teenagers have nothing to do but lie in ambush, zip around town on mopeds, pretend to be adults. It’s an island where girls are doomed from the start to become ‘turtles’—women crushed under their husband’s oppression—or to slide into the bottomless ravine carved by prostitution and drugs.”

Eve stands out. She earns money with her body, but seeks to grasp her destiny. For Le Clézio, she is the star gleaming “deep within Troumaron’s darkness, a marrone escaping from slavery into unfriendly forests and towering buildings. And she is the living, beating heart of this broken world.” From the beginning, given her personality, the question arises: how she will evolve, and will she eventually escape?

Mauritian Writer Ananda Devi — her succinct graphic sentences convey sensual and even poetic imagery. French Culture.org

The narrative structure contributes to the suspense, as one monologue follows another but does not necessarily pick up immediately on acts described in the preceding one. An atmosphere of youthful recklessness and doom hovers over Troumaron. Then the tragedy occurs: loving, caring Savita is discovered, dead, in a trash bin. Determining what actually happened and the murderer’s identity thereafter forms the intrigue propelling the second half of the plot forward.

But it would be a mistake to call Eve out of her Ruins a mystery novel or even a novel exclusively devoted to social realities. Devi’s succinct graphic sentences, which vividly evoke such events, also convey sensual and even poetic imagery. Poetry remains a permanent, if mostly remote horizon, a sort of reminder of “something else” in the harsh world in which the characters must survive. In a story aimed at tragedy from the onset, aspirations—involving love or the hope for survival elsewhere—somehow seem viable, even as Saad, the gang member, suddenly listens, in a class full of uproarious mocking students, to his French teacher reciting Rimbaud’s poem about the colors of vowels.

Describing himself and, implicitly, the three other characters, Clélio admits: “I don’t know where to go. I keep going round and round. Like I’ll bite off my tail.” But he imagines himself joining his brother in France, even if he knows that his brother has surely failed there. Perhaps one or two of these characters will squirm him- or herself out of the tight grip of fate and attain another life far away from this vicious dead-end of a place where “la vraie vie” that they envision—genuine life, real life, true life—“is absent,” as Rimbaud put it.

John Taylor has recently translated Pierre Chappuis’ Like Bits of Wind: Selected Poetry and Poetic Prose and Catherine Colomb’s novel The Spirits of the Earth—both books available from Seagull. His most recent book of short prose is If Night is Falling (Bitter Oleander Press), along with two bilingual volumes of poetry published in France: Hublots / Portholes (L’Œil ébloui) and Boire à la source / Drink from the Source (Voix d’encre). John Taylor’s website.

Tagged: Ananda Devi, Deep Vellum, Eve out of Ruins, French translation