Book Review: A Superb Biography of French Filmmaker Éric Rohmer

The publication of de Baecque and Herpe’s wonderful biography needs to be followed in the USA by a complete Éric Rohmer retrospective.

By Gerald Peary

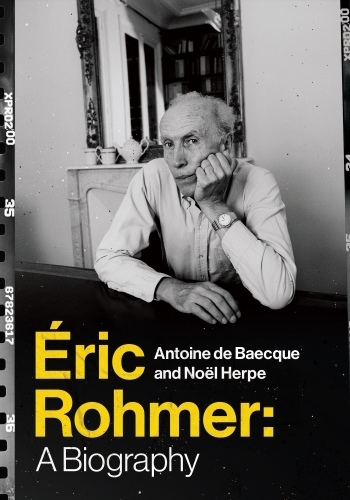

“I guard my secrets jealously,” said French filmmaker Éric Rohmer (1920-2010), the most obsessively private of artists. One might have expected that he would have ordered his papers burned at his death. Fortunately, no, and the deposit in a Rohmer archive of fifty boxes of his personal holdings containing 20,000 documents made possible the excellent, probably definitive Éric Rohmer: A Biography by Noël Herpe and Antoine de Baecque (Columbia University Press, 608 pages, $40). The latter critic, ex-editor of Cahiers du Cinéma, is also responsible for superb biographies of Rohmer’s cohorts, Jean-Luc Godard and François Truffaut. Nobody knows the French Nouvelle Vague better than de Baecque and also its entwined Cahiers du Cinema connection: how influential Cahiers film critics turned world-class filmmakers, including Rohmer.

Though this biography is immensely long, and certainly exhaustive, the subject of the book exits the book with the image he projected of himself intact. A clean-living Christian, a devoted son, an upstanding husband and father. There are literally no scandals in Rohmer’s 90 years on earth. Like Alfred Hitchcock, about whom he co-authored the first book ever (Hitchcock: the First Forty-Four Films, with Claude Chabrol), he was a devout Catholic churchgoer who was faithful to his wife while having fantasy relationships with the beautiful young actresses who came his way. But while Hitchcock terrorized and stalked the women he couldn’t have, Rohmer flirted with them harmlessly in his office over cups of tea.

I once interviewed the actress Sophie Renoir, and she expressed great affection for her director Rohmer, who chatted her up at tea time. I also once interviewed Rohmer around 1978, when he was at the New York Film Festival with his medieval-set Perceval. True to his reputation, he sat in a hotel room among an entourage of lovely, very youthful French actresses, and everyone seemed relaxed and happy. All was chaste, like a birthday party for a beloved “mon oncle.“

Clearly, Rohmer was cognizant of the decadent reputation of filmmaking. That’s the reason behind his most famous secret, changing his name for his director career from his authentic one, Maurice Schérer. That way, his conservative mother, who lived in a small town in central France, would never find out that he indulged in movie making. “It would have killed her,” he said, and she died never knowing. In his home life, in the evenings away from the set, he was Schérer. His wife never came to watch him work nor did his two sons. He spent quality time with all of them, he was never an absentee husband or father, but cinema was off limits. His identity with his family was grounded in his other abiding persona: a career university professor and lecturer, not only speaking theoretically about cinema but also knowledgeably about philosophy, the classics, German, Latin. Rohmer was extraordinarily learned, a consummate intellectual.

If there is anything discomforting about Rohmer it is his right-wing sympathies. Though hardly a political activist, he hung out in his 20s with disreputable nihilists who feigned an allegiance to the Nazis. He was strongly nationalist and colonialist in France’s fights with Algeria. Frankly, he was a racist, who spoke against the mingling of outsider perspectives in French culture. His biographers: “He didn’t like Hiroshima, Mon Amour because he couldn’t understand how a French woman could fall in love with an Asian.”

His biographers continue: “…in his whole work, no character is black, Eurasian, or North African…Rohmer’s ideal system is aristocratic and white.” Only in his first feature, The Sign of Leo, the story of a downtrodden bum, did Rohmer shoot in the seedy streets of subterranean Paris. His other nineteen features are all located in the prettified, gentrified world of the French bourgeoisie.

Again, his biographers: “Hearing it said he made reactionary films hardly bothered Rohmer at all. He would have found it far less tolerable to be accused of making bad films.” Philosophized Rohmer about his profoundly non-avant garde cinema: “Tradition is not behind us but ahead of us, it constitutes the true modernity.” Making Kleist’s early 19th century Marquise of O, the filmmaker reiterated his retro aesthetic: “Rejuvenating the work does not mean, for us, modernizing it but rather returning it to its time.”

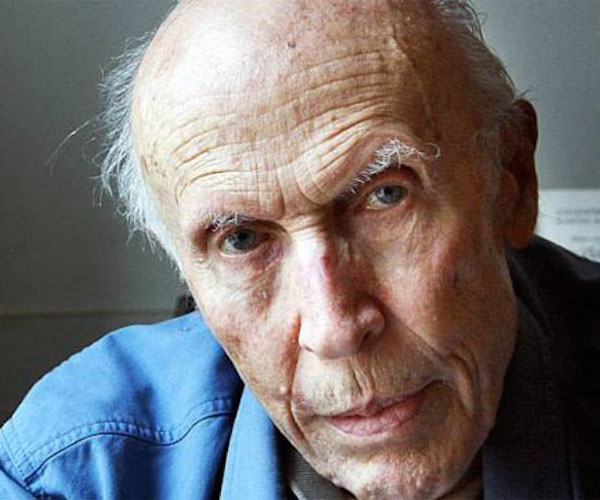

Director Éric Rohmer — “Tradition is not behind us but ahead of us, it constitutes the true modernity.” Photo: Jean Vigo Institute.

For me, as a film critic, the most intriguing pages of the book are those dealing with Rohmer’s years at Cahiers du Cinéma. He was a polemical writer of lengthy, sometimes wearisome essays, usually about “auteurist” Hollywood cinema. He became Editor-in-Chief of the publication after the death of its legendary founder, André Bazin. I learned about the internal debates at the magazine and of a coup d’etat in which Rohmer was deposed by Jacques Rivette. His pal, Truffaut, was among the co-conspirators.

The least fruitful part of the biography? The elongated discussions of Rohmer’s twenty features. That’s not the fault at all of the writers of the book. The problem is that in America, the great bulk of Rohmer’s movies came through once and never again. I savored the chapters on My Night at Maude’s, Claire’s Knee, Chloe in the Afternoon, as I’ve seen these early classics enough times to remember the details. But later Rohmer cinema is a blur of well-dressed, nice-looking young French people saying witty things. Which is A Tale of Summer and which is A Tale of Winter?

The solution is simple: the publication of de Baecque and Herpe’s wonderful book needs to be followed in the USA by a complete Éric Rohmer retrospective. The Harvard Film Archive, are you listening?

Gerald Peary is a retired film studies professor at Suffolk University, Boston, curator of the Boston University Cinematheque, and the general editor of the “Conversations with Filmmakers” series from the University Press of Mississippi. A critic for the late Boston Phoenix, he is the author of nine books on cinema, writer-director of the documentaries For the Love of Movies: the Story of American Film Criticism and Archie’s Betty, and a featured actor in the 2013 independent narrative Computer Chess.

Tagged: Antoine de Baecque, Cahiers du Cinema, Columbia University Press, Éric Rohmer

“…in his whole work, no character is black, Eurasian, or North African” – wasn’t Béatrice Romand born in Algeria?