Dance Review: Bill T. Jones — Pieces of a Conversation

Bill T. Jones considers himself an heir of the postmodern dancers, and like them he rejects dance’s received ideas of codified movement and established theater conventions.

A Letter to My Nephew, directed by Bill T. Jones. Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Company at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston, through November 13.

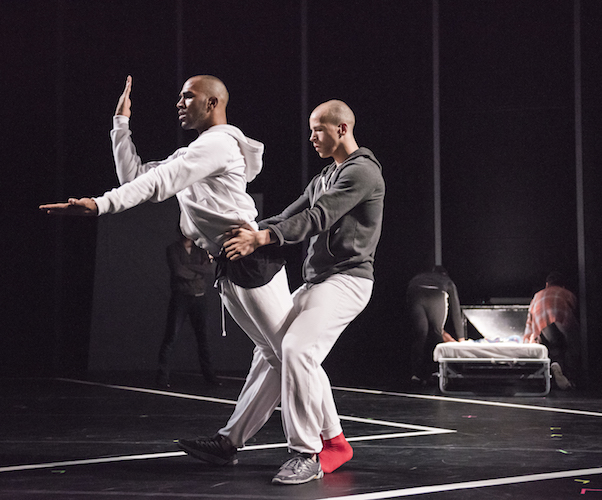

Cain Coleman Jr. and Talli Jackson performing in “A Letter to My Nephew.” Photo: Liza Voll.

By Marcia B. Siegel

“The dance is like a list, an episodic collage. We’re trying to understand this country and Europe in the light of Ferguson and other events,” Bill T. Jones said in a pre-performance talk at the ICA on Friday night. He was surprisingly reticent about the tumultuous political situation in recent months, especially the week’s election results. Asked to comment on that by a member of the pre-performance audience, he seemed, for a change, without words. After seeing the performance, I thought Jones is more effective in an allusive mode than when he explains.

A Letter to My Nephew originated in letters Jones writes from wherever he is on his world tours to his hospitalized nephew, Lance T. Briggs. The dance takes place in disconnected scenes, and the eight company dancers toggle identities, between being anonymous performers and more recognizable characters. The stage is almost bare, with moody lighting that brings out sectors of the action.

Jones explained that A Letter is site-specific. It’s been done in Singapore and the suburbs of Paris and it changes to reflect the venue. The Boston installment, put together at the ICA by company associate artistic director Janet Wong, was billed as a US premiere. It began with a few projected words from a letter about the nice fall weather here in Boston. I noticed one other recognizable local reference, a projected photograph of a famous view: Old North Church, with Paul Revere’s statue in the foreground. But the dance itself seemed to be more generic.

A double runway is laid out on the floor in the form of a cross. Sketchy props and objects are brought in by the dancers. Unlike the storytelling and text recitations in many of Jones’s earlier pieces, words aren’t explicit here. But they’re ever-present, in fragmentary phrases projected on a screen, or exaggeratedly drawn-out lyrics (“deep river,” “parlez-moi d’amour”) or over-amplified speeches where you can only understand the affect.

Jones worked with his longtime associates for the piece: Bjorn Amelan, décor; Robert Wierzel, lighting; Liz Prince, costumes; and Janet Wong, projections. The evocative score for voice and keyboards is performed by Nick Hallett, composer; Matthew Gamble, baritone; and DJTONYMONKEY, alias company dancer Antonio Brown.

Letter begins, after those few projected words, with a stealthy mugging that escalates into a large-scale gang fight, amplified screams, stomps, and falling bodies. Nearly all the brawlers are faceless under their hoodies. Abruptly the mayhem ends. We hear Jones’s voice slowly counting – one to forty-five – over the sound of a mob. One by one, dancers rise out of the mass of fallen bodies and strut toward the audience with gestures and attitudes that suggest various marginal characters. A sneering adolescent, a street punk, a prostitute. One man (Cain Coleman Jr.) wears red socks and white sweats, and minces down a diagonal on half-toe as if he’s wearing high heels, like a model in a Harlem vogue ball.

After that I remember sensuous duets that melted from erotic body contact into acrobatic wrestling and combat. Male couples, female couples, none of them looking conventionally romantic, and some of them shadowed by Coleman on a folding bed with other partners. Talli Jackson, who emerged in the first of several runway processions aggressively holding his crotch, later did two solos in which he appeared to be tying himself in knots.

The company now comprises a variety of physical types, tall and short, thin and husky. They’re wonderfully flexible, slipping through Jones’s choreographic mélange of hip hop dancing, made-up gestures, ballet, modern dance, and contact improvisation moves; and freezing midstream in expressionistic poses. As a group they assemble in protective clusters, assertive lineups, and potentially hostile gangs.

Working together, they lift and move the large screen, to disclose

terse phrases and questions: Do you feel safe? Did you vote? Remember when you were a student at the San Francisco Ballet School? Most of the words don’t directly seem to relate to the action, but the ballet school reference brings about a pseudo-ballet class. The dancers spread themselves evenly in the space, facing in different directions, and do classroom exercises together. In a later diagonal procession, some of them jump with their feet twisting in entrechats, others leap with their partners from side to side.

During the “classroom” interlude, two dancers glide through carrying long white poles. Eventually they use these props to build a boxlike structure without walls or ceiling that serves as a sort of stage for more solos, and can also shelter a group milling together. A Letter concludes with a video clip of a young man, presumably the real Lance, lying in bed, speaking some fast, indistinct lines that are unmistakably harsh.

Dancers performing in “A Letter to My Nephew.” Photo: Liza Voll.

A Letter may be a spinoff from section two of a planned trilogy, Lance: Pretty AKA The Escape Artist, which was shown in New York last month. From accounts of the Lance piece, it must be quite different from A Letter. It tells Lance’s story, beginning with his childhood dance lessons, his life as a model and descent onto the streets, culminating in addiction, prostitution, and eventually a paralytic illness.

It’s not unusual for Bill T. Jones to recycle material from one dance into another. Works like A Letter reinforce the company repertory without requiring new choreography. Janet Wong’s stalwart directing keeps the material vital. Jones considers himself an heir of the postmodern dancers, and like them he rejects dance’s received ideas of codified movement and established theater conventions. In A Letter, he makes reference to some of his postmodern mentors and models, Trisha Brown, Elizabeth Streb, Meredith Monk’s nonverbal chanting, the contact improvisation he and his late partner Arnie Zane learned in the ’70s.

He also thinks of movement as an expressive medium in itself, an abstraction of feelings and relationships. He cares about social issues as well as personal ones, and he wants his dance to set a moral lesson, about history and about community. In that way, he’s also an heir of the earlier modern dancers. A Letter only alluded to social and political realities, but it often jolted you out into the streets and the gay clubs.

Driving in and out of Boston Friday night, we noted that the Zakim Bridge was lit up in blue. Another piece of the conversation perhaps.

Internationally known writer, lecturer, and teacher Marcia B. Siegel covered dance for 16 years at The Boston Phoenix. She is a contributing editor for The Hudson Review. The fourth collection of Siegel’s reviews and essays, Mirrors and Scrims—The Life and Afterlife of Ballet, won the 2010 Selma Jeanne Cohen prize from the American Society for Aesthetics. Her other books include studies of Twyla Tharp, Doris Humphrey, and American choreography. From 1983 to 1996, Siegel was a member of the resident faculty of the Department of Performance Studies, Tisch School of the Arts, New York University.