Book Review: The Joy and Glory of Virgil Thomson’s “The State of Music & Other Writings”

Library of America’s volumes of the writings of Virgil Thomson will help reestablish him as one of the 20th century’s preeminent musical scribes.

By Jonathan Blumhofer

What do you get when you combine an authoritative writing style, dashes of wit, and a big helping of ego? Probably something approaching The State of Music & Other Writings, the second of the Library of America’s two-installment Tim Page-edited Virgil Thomson series (The Arts Fuse interviewed Page about 2014’s Music Chronicles.) An anthology of eleven groupings of Thomson’s writings, it further reveals Thomson’s aesthetic philosophy and helps reestablish him as one of the 20th century’s preeminent musical scribes. At the same time, his partialities and prejudices shine through the writings in this compendium in ways more problematic than they appear in Thomson’s reviews.

The difficulty is most pronounced in Virgil Thomson, the composer’s mid-1960s autobiography, which, if it doesn’t paint him as the sun around which the 20th-century’s early musical history orbited, then something pretty close to it. Of course, Thomson was fortunate to pass a good part of the ‘20s and ‘30s in Paris, hanging with the likes of Copland, Stravinsky, Milhaud, Joyce, and Picasso. Literature – and, especially, his long friendship/collaboration with Gertrude Stein – looms large.

Still, you have to take more than a few of his claims with a grain or two of salt. Did Serge Koussevitzky really become music director of the Boston Symphony Orchestra because of the then-twenty-eight-year-old Thomson’s reviews of him? Was his opera, Four Saints in Three Acts, really the American equivalent of Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring, its premiere provoking one of the great scandals in American musical history? No and not really.

And so on.

Having said that, the autobiography’s pages are dotted with fascinating and sometimes unexpected characters. Who knew that none other than H.L. Mencken got Thomson started writing about music? “Write me an article,” America’s greatest cultural critic commanded the then-twenty-six-year-old Thomson, “answering the questions: ‘What is jazz?’ Everybody talks about it; nobody defines it.” The piece – what Thomson describes as the first (or near that) technical description of jazz – appeared in The American Mercury shortly thereafter.

And it’s remarkable to note the variety of many of Thomson’s friends and acquaintances, the lives of whom spanned the 19th century to the 21st. John Cage and Lou Harrison turn up. So does Edward Burlingame Hill and Archibald Davison, the latter a key musical figure at Harvard. It’s appropriate and welcome to read Thomson’s first-hand account of the legendary pedagogue Nadia Boulanger – “a tall, soft-haired brunette still luscious to the eye,” is how he described her – with whom he studied in Paris.

Naturally, Thomson’s extensive travels figure prominently in the story. Local readers might bristle a bit at his observations of New England nearly a century ago, but others may recognize some truth in them yet. In one chapter, Thomson describes Cambridge as “a gastronomic desert,” before going to list superior Boston establishments (which include Jacob Wirth’s, Durgin Park, and the Boston Oyster House). Thomson’s ambivalence about Boston – a city in which “no one expands; the inhabitants seem rather to aim at compressing one another” – is pronounced and he wasn’t much more enthusiastic about Central Massachusetts (“Paris was warmhearted and harsh, like Kansas City; Whitinsville was neither of these,” he writes of a winter passed at the home of Chester and Jessie Lassell in that south-central Massachusetts hamlet). The places he really seemed to love were his boyhood home of Kansas City, New York, and Paris.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, what’s missing in the autobiography is anything too personal. There’s no discussion of his homosexuality. Nor is there, really, any analysis of his music (which, today, might help bring it in a bit from the cold). Of course, Thomson wasn’t known for being the most analytical of critics – his famous comment, for instance, that Sibelius is “provincial beyond all description” lacks any exegesis whatsoever – so maybe that last omission isn’t as glaring as it seems. But it’s a missed opportunity, all the same.

That said, if one can sift through the egoism and the bias inherent in not a few of these pages and not become too dulled by the social-calendar-report quality of some stretches, Thomson’s characterizations of the lively cultural scenes he inhabited are warm-hearted and fun to read. Yes, the book is a warning against relying too closely on first-hand accounts for historical accuracy – and, in some regards, a demonstration of how not to write an autobiography – but, for color and verve, Thomson not at his best is still a hard author to beat.

The same is largely true of The State of Music, the short 1939 book (presented here in Thomson’s 1961 revision) that secured him his critic’s perch at the New York Herald Tribune in 1940. It has aged and some parts of it not all that well: his discussion of the lives of painters, poets, and whatnot, for instance, is shallow, though I suppose there’s something to be said for the breezy generalities he tosses off so confidently. To wit,

If the poet works at a regular job, he hasn’t got enough time to shake around and keep his ideas in solution. He crystallizes. If he doesn’t work at a regular job, he has too much leisure to spend and no money. He gets into debt and bad health, eats on his own soul. It is very much too bad that his working-life includes so little of sedative routine.

There’s more like this throughout the book.

State’s musical chapters – two of the first three place music at the center of an artistic ecosystem which, judging in part from his autobiography, seems to have mirrored Thomson’s experience – range to cover everything from the practical (“Who does what to whom and who gets paid” is the subtitle of the sixth chapter) to aesthetic (“The economic determinism of musical style”) and much in between (“How modern music gets that way”). Sometimes Thomson’s thoughts tend in directions today’s composers and audiences will clearly recognize: he discusses film music in some depth (and, in that context, the marriage of “noises and music”), covers the intersection of politics and music, and engages with the divide between professional musicians and their non-professional concert-going audiences.

His conclusions oftentimes have a way of slashing through to the heart of the matter. “The whole concept of mass culture is obscurantist,” he writes in one chapter. “Does Shakespeare or Beethoven or the Bible lose quality through becoming massively available? No…Then, to speak of our enormous facilities, through publication and radio, of distributing art, information, and entertainment as a sociological phenomenon to be worried over under the name of mass culture, but not really to be changed or controlled, is not a culture concept at all but a political one.”

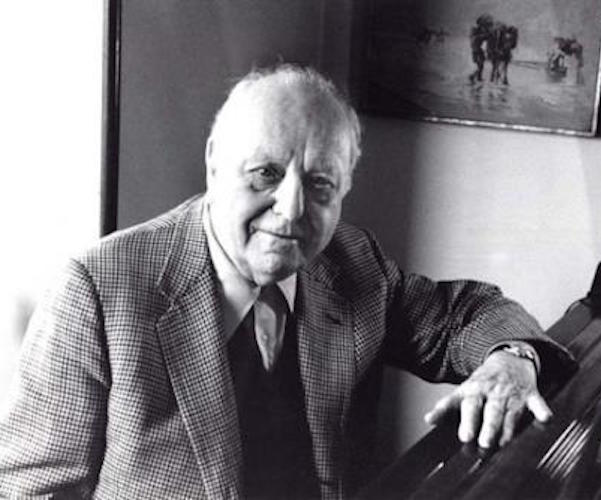

Composer and critic Virgil Thomson — his life was staggeringly rich and thoroughly documented.

And, in perhaps its finest moments, State provides an unapologetic, muscular defense of the essential art of criticism. As Thomson saw it, criticism was an integral part of the “assimilation-process” of the collaborative arts. “The third man,” he writes (the first two are the composer and performer), “must analyze the audition [performance] into its two main components. He must separate in his own mind the personal charm or brilliance of the executant from the composer’s material and construction. This separation is a critical act, and it is necessary to the comprehension of any collaborative art-work.” At a time when such “necessary” work is increasingly dismissed as irrelevant and worthless, Thomson’s rhetoric comes across as a breath of fresh, common sense.

The remainder of the anthology is given over to excerpts from American Music Since 1910 (a fine, if somewhat selective, discussion of contemporary music that runs through, roughly, 1970), Music with Words (an insightful essay on setting, well, words to music), and various other writings that cover the last decades of Thomson’s life (he died, aged ninety-two, in 1989). Topics here range from a discussion of the ups and downs of American opera (“…nor do I share the idea, commonly expressed in this country, that our sophisticated Broadway musicals are evolving towards opera. They are not extending composition or choreography; they are diluting them for easy sale”) to a review of Stravinsky’s The Flood (“twenty-three minutes of playing-time dispose of the whole work, and neither sustained musical development nor any climactic loudness is ever mobilized”) to tributes and reminiscences of various important figures in Thomson’s life (including Nadia Boulanger, William Flanagan, and Lou Harrison) and the collection ends with a series of book reviews.

What to make of it all, then? In sum, The State of Music & Other Writings is a remarkable, if flawed, bounty for anyone interested in American music, specifically, or 20th-century Western culture, generally. As revealed in these pages, Thomson’s life was staggeringly rich and thoroughly documented. Like his criticism, it’s marred by conflicts of interest and some fairly apparent biases. But that doesn’t diminish its worth.

Indeed, as in the earlier Music Chronicles anthology, there’s plenty here to disagree and argue with: Thomson’s dismissal of the music of George Whitefield Chadwick and Edward MacDowell, for instance, as a “thin perfume…of another time and place than 20th-century America” completely misses the point that both 19th-century composers (in style and outlook) were thoroughly men of their age, not Thomson’s. But these things are part of the joy and glory of reading and interacting with a writer of Thomson’s caliber and intellect. And, given the lack of intellectual rigor, the embrace of illogic and unreason, the celebration of Know-Nothingism that permeates so much of our current cultural (not to mention political) discourse, engaging with Thomson today is perhaps more of a tonic – necessary and curative – than it was even when he lived.

Jonathan Blumhofer is a composer and violist who has been active in the greater Boston area since 2004. His music has received numerous awards and been performed by various ensembles, including the American Composers Orchestra, Kiev Philharmonic, Camerata Chicago, Xanthos Ensemble, and Juventas New Music Group. Since receiving his doctorate from Boston University in 2010, Jon has taught at Clark University, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and online for the University of Phoenix, in addition to writing music criticism for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette.

Tagged: Library-of-America, Music Criticism, The State of Music and Other Writings, Tim Page