Arts Interview: Tim Page on the “Virgil Thomson: Music Chronicles, 1940-1954”

The Library of America volume contains a generous sampling of Virgil Thomson’s best music criticism – trenchant, outspoken, oftentimes delightfully clever, and always assured.

By Jonathan Blumhofer

The list of truly influential music critics is a pretty short one and the tally of composers who have worked in the profession and left any lasting mark on it even briefer. In the 19th century, the writings of Robert Schumann and Hector Berlioz were arguably on par with those of E.T.A. Hoffmann, Eduard Hanslick, and John Sullivan Dwight, while, in the 20th, the forthright wit of Virgil Thomson (1896-1989) set a bar that has been often imitated but rarely matched.

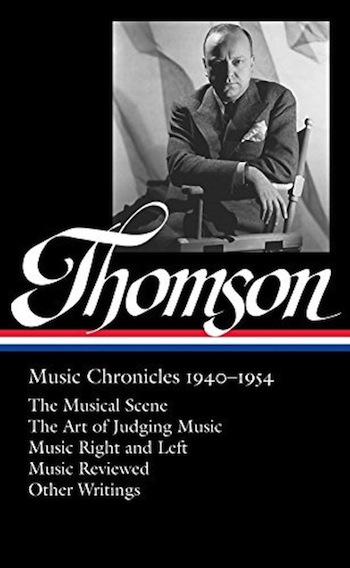

Part of that greatest generation of American-born composers (George Gershwin, Duke Ellington, Aaron Copland, Elliott Carter, William Schuman, Roy Harris, Leonard Bernstein, and Leon Kirchner were all his contemporaries or thereabout), Thomson’s music is largely overlooked today, though a handful of pieces (such as his collaboration with Gertrude Stein, Four Saints in Three Acts) remain ensconced on the fringes of the repertoire. His writings on music – trenchant, outspoken, oftentimes delightfully clever and always assured – are, also, probably better known today by reputation than anything else, in large part because they’ve been out of print for so long. This fall, though, to commemorate the twenty-fifth anniversary of Thomson’s death, the Library of America has rectified that neglect by publishing Musical Chronicles, 1940-1954 (1200 pages, $45), a collection of some of the best of Thomson’s criticism for the New York Herald Tribune. Originally collected in four now out-of-print books between 1945 and 1967, Musical Chronicles surveys the remarkably rich cultural scene in and around New York in the middle of the 20th century – and, perhaps most interestingly, over the war years.

Tim Page, USC professor, Pulitzer Prize-winning critic, and former Thomson colleague, served as editor of the project and kindly answered several questions I posed him (via email) on Thomson’s career, his work as a composer, and the role of criticism as a form of education.

Arts Fuse: Thomson was surely one of the most outspoken and lively music critics on record, but even in his prime he wasn’t the only important figure in the field: his career overlapped with some other significant writers on music (one thinks of Olin Downes, Alan Rich, and Harold Schonberg, for instance). What do you think is Thomson’s place is in the firmament of mid-century music criticism? How, too, would do you say Thomson fits in among the great 20th-century critical voices (not just of music, but of art, literature, theater, etc.)?

Critic and editor Tim Page — “You don’t have to agree with Virgil to enjoy reading him. Indeed, I often find that disagreeing with a critic is a good way to develop your own aesthetic.” Photo: USC.

Tim Page: What makes Virgil so wonderfully interesting is his use of the English language and his ability to convey pretty complicated musical ideas in terms that the layperson could understand. His greatest competition during his time at the Herald Tribune (1940-1954) was Olin Downes, who wrote rather in the manner that I would expect of a hippopotamus. Still, I often find myself agreeing with Downes over Thomson – on Sibelius, on Mahler, sometimes on Toscanini and Heifetz. Alan and Harold, both important critics, were really another generation, and have their own strengths and weaknesses.

AF: For me, one of the most refreshing aspects of the LOA collection come from reading Thomson’s views on pieces (and composers) with which I completely disagree. He dismisses Sibelius in cutting fashion. His summary of Leonard Bernstein’s Jeremiah Symphony is brusque. And so forth. Could you speak to some of the criteria he used to adjudicate new music? Could you also discuss his criteria for reviewing the standard repertoire?

Page: That’s it exactly – you don’t have to agree with Virgil to enjoy reading him. Indeed, I often find that disagreeing with a critic is a good way to develop your own aesthetic. I got into this line of work because I wanted to argue with a lot of prevailing views. One thing I will say for Virgil is that he managed to review – and review intelligently and with some support – a lot of new music that had nothing in common with his own. That’s rare among composers. As for the standard repertory, he took nothing for granted. If he wanted to take apart the “Missa Solemnis,” he would – and even those of us who love the “Missa” would agree that it just might be, as Virgil suggested, “too high and too loud too much of the time.”

AF: Many of Thomson’s reviews of certain conductors and ensembles (John Barbirolli, Toscanini, and the New York Philharmonic, for instance) are either reliably scathing or he repeatedly comes across as distinctly unimpressed. Is any of this due to ax grinding or was Thomson generally above such things?

Page: Virgil certainly wasn’t “above” such things. He was deeply compromised by his friendships (his buddies were all but guaranteed rave reviews) and his own hunger to push his own work (he would regularly visit cities that were playing his music and write glowingly of the orchestras and conductors who played it). This is a serious debit, in my opinion, and has to be addressed in any summary of his writing.

AF: Thomson was part of a remarkable generation of American symphonists: Aaron Copland, Roy Harris, William Schuman, George Antheil, Elliott Carter, and Leonard Bernstein were a few of his contemporaries (or near contemporaries). Could you talk a bit about his relationships (professional and personal) with them? How would you say he fits (or should fit) into the pantheon of important 20th-century American composers?

Page: Copland was the one he admired most, although he recognized Bernstein’s gifts as a conductor and – especially and invariably – as an educator. He called Bernstein “the ideal explainer of music, past and present.” Virgil was probably closest personally to Antheil, when they knew each other in Paris in the 1920s, and he usually reviewed his work fondly. He disliked Schuman deeply in later years, most likely because Schuman all but ran New York concert music in the postwar era (as President first of Juilliard and then of Lincoln Center) and Schuman was not a great admirer of Thomson’s music. That was strike one, two, and three with Virgil, although he wrote encouragingly of Schuman’s early work. Virgil likened Roy Harris to Sibelius – not a compliment in Thomson’s world. He admired Carter’s early work but found him rather grand in later life. I remember him saying something like “at least when Aaron got to the top, he sent down the elevator for the other boys!” Late in life, he grew friendly with Philip Glass. “He writes operas in Sanskrit, I wrote them in Stein,” he said to explain their closeness. As for Virgil’s own work, there is much that is wonderful (the Stein operas, the Cello Concerto, some of the film music) and a lot that seems note-spinning. But we usually remember our composers by their best works, and his best is very beautiful indeed.

Virgil Thomson. Photographed by Carl Van Vechten, June 4, 1947.

AF: On a related note, did Thomson view himself primarily as a composer or as a critic? And did he ever manage a satisfactory balance between the two “professions”?

Page: He always considered himself a composer, first and foremost, and believed that he listened and wrote prose as a composer.

AF: In discussing your own criticism, you have spoken time and again about your reviews having an educational component. Thomson, presumably, wrote for a more musically literate audience, yet his writing is eminently readable. What does Thomson’s style of urbane, highly-educated music criticism have to say to us today?

Page: Any good critic should be an educator on some level, although too much pedantry will turn off your reader quickly. If you watch the Bernstein “Young People’s Concerts” today, they are astonishingly sophisticated. Bernstein assumes a level of knowledge at the beginning of each show that is vastly above the level of your average New York Philharmonic ticket holder today, and that’s before he’s begun to deliver his lesson. What has happened to music training in this country is horrible. Still, I’m always surprised by how easily people comprehend Virgil’s writings – if there is a strange new idea, he usually puts it in context or gives some brief explanation. The best we can hope for is to convey some information and some passion and some wit. You never know what will inspire somebody to go further.

Jonathan Blumhofer is a composer and violist who has been active in the greater Boston area since 2004. His music has received numerous awards and been performed by various ensembles, including the American Composers Orchestra, Kiev Philharmonic, Camerata Chicago, Xanthos Ensemble, and Juventas New Music Group. Since receiving his doctorate from Boston University in 2010, Jon has taught at Clark University, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and online for the University of Phoenix, in addition to writing music criticism for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette.

Tagged: Classical Music Criticism, Herald Tribune, Music Criticism, The LIbrary of America, Tim Page