Film Interview: A Brief Conversation with Filmmaker Peter Flynn

The film looks at the history of film projection by way of the projectionists themselves: men and women who have skillfully and lovingly performed this work for decades in arthouse theatres, drive-ins, and even porn palaces around the country.

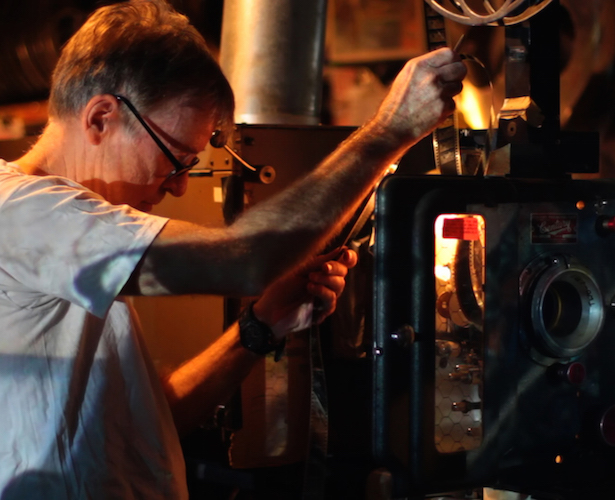

Dave Leamon, projecting at the Brattle Theatre, from the film “The Dying of the Light.” Photo: Courtesy of Peter Flynn.

By Peg Aloi

Boston documentarian and film scholar Peter Flynn is garnering considerable praise for his feature-length film The Dying of the Light, which premieres at Brookline’s Coolidge Corner Theatre tonight (with Flynn and special guests in attendance), followed by a one week engagement. The film looks at the history of film projection by way of the projectionists themselves: men and women who have skillfully and lovingly performed this work for decades in arthouse theatres, drive-ins, and even porn palaces around the country. I asked Peter (a long time friend and former colleague of mine from Emerson College from when I taught film studies there) a few questions about the film, which was recently picked up for distribution by First Run Features.

The Arts Fuse: Did you have one particular moment or insight that convinced you of the importance of this project?

Peter Flynn: It was pretty early on, after I had already been shooting some footage. I was in upstate New York interviewing Bob Throop, the projectionist at the Capitol Theatre. I had planned to go back and shoot some more with him, but two weeks after our last conversation, he died. This was very sad but also underscored the urgency of the work, because there are people passing away, and with them an entire tradition that is passing away. It was already a labor of love, but at that point I knew I had to keep trying to capture it before it all went away for good.

AF: One subject the films covers is the conversion of so many theatres to digital projection, which of course for some filmgoers means a loss of quality in sound and picture quality. The projectionist at the Somerville Theatre says in the film that when people have to choose between quality and convenience, they almost always go with convenience. We see this also with people listening to digitized music instead of analog, or watching TV on their smart phones. Why do you think people no longer care about the sound or visual quality of these experiences?

Flynn: I think they’ve been conditioned not to care. It’s been a slow devolution but you can trace it back to automation in the projection booth in the 1970s, and then later stages of film presentation when the films were plattered. The whole process was no longer run by experienced projectionists but by poorly-paid workers with little or no projecting experience. If something went wrong, and the workers couldn’t fix it, the theatres would just offer patrons a free ticket. If you really look at the economics of how most movie theatres operate now, you see that it makes no sense for them to go to the trouble of worrying about things like picture quality. People complaining about it means an actual increase to their bottom line, because a free ticket means that a customer will come back and spend their money at the concession stand, which is where most theatres make the bulk of their profits. In this business model, there is really no incentive to put on a good show; in fact the incentive is to do the opposite!

AF: And most of the time we have to watch commercials, too!

Flynn: Exactly, and we don’t even complain about it anymore. You and I are from a generation where we had a different set of expectations for the quality of our movie going experience. But your average 30 year old, and definitely your average 20 year old, they don’t have these expectations.

AF: I love old theatres and one of the most striking things about watching this film for me was the sight of some of these great old picture palaces that have been all but gutted. It’s heartbreaking.

Flynn: It is, and what’s true of these buildings has really become true for most aspects of post-industrial America: we no longer build things to last or to be beautiful. These old theatres are tombs or relics to a forgotten culture. The image of the abandoned, broken down theatre is a metaphor of the culture that has been lost.

AF: The film suggests that perhaps the unusual spectacle of 70mm films might be a way to rejuvenate the art of film projection. Despite The Hateful 8 not doing so well…

Flynn: The ending has yet to be written on this, I think. The reviews weren’t so positive overall for The Hateful 8. And yet the arthouse theatres that showed it did great, because people wanted that experience of seeing it in 70mm. The astronomical cost of installing these projectors is a big factor, and of course makes it even more important to have trained professionals who can use them properly.

AF: I was struck by the words of one projectionist who said he had learned projection from people who had studied in 1910, and since he worked for fifty years, his knowledge and skills spanned a hundred years of tradition. And that it was all passed down from person to person, not learned in books. This is mind boggling. Is the loss of the art of film projection like a language that’s dying out?

Flynn: Yes, the whole culture is comparable to an oral tradition. There are no textbooks, you can’t go to school to learn it, you have to be an apprentice and learn it directly by watching others and doing it. Those projectionists whose jobs are disappearing, if they want to keep working with film they can maybe become archivists, or preservationists, but it’s not the same, and this knowledge will die with them. This is it, the end of the line.

AF: I worked at an arthouse in Northampton when I was in grad school, and the projection booth was just off our tiny lobby, and it was like the projectionists had their own little world in there.

Flynn: The projection booth is the site of arrested development, and time moves differently there. It kind of slows down a bit. The people who work in the booth, they may not be trapped in the past but they do move at a different pace. It’s a very interesting place, that booth.

Peg Aloi is a former film critic for The Boston Phoenix. She has taught film studies for a number of years at Emerson College and is currently teaching media studies at SUNY New Paltz. Her reviews have appeared in Art New England and Cinefantastique Online, and she writes a media blog for Patheos.com called The Witching Hour.

Tagged: documentary, film projection, Peg Aloi, Peter Flynn, projectionists