Visual Arts Review: Picasso at the MFA

This exhibition at the MFA gives us as chance to walk about a delightful island in the wide sea of Picasso works.

Visiting Masterpieces: Pairing Picasso, at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, MA, through June 26.

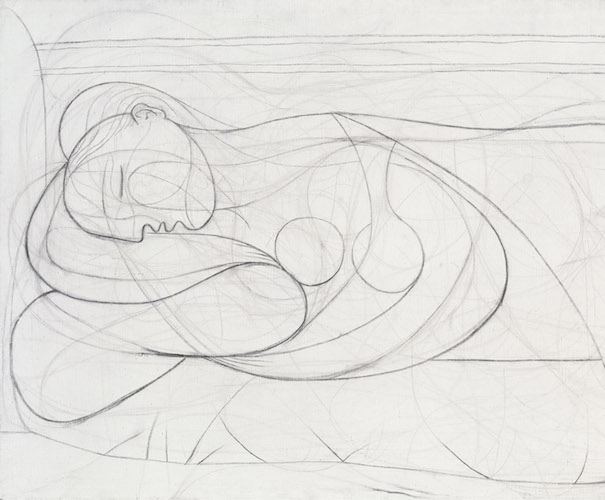

Pablo Picasso, “Sleeping Nude,” 1932. Photo: Courtesy of the Museum of Fine Arts Boston.

By Kathleen C. Stone

Picasso was among the most prolific of artists. Most weeks, he created multiple canvases, and at his death left behind enough to supply museums the world over, including those in Paris, Barcelona, and elsewhere devoted exclusively to his oeuvre. How refreshing, then, that the Museum of Fine Arts is showing just eleven works, carefully grouped, as a study of how the artist approached and reapproached a subject. With work from the Beyeler Foundation in Switzerland, private collections, and the MFA, we have been given a chance to walk about a delightful island in the wide sea of Picasso works.

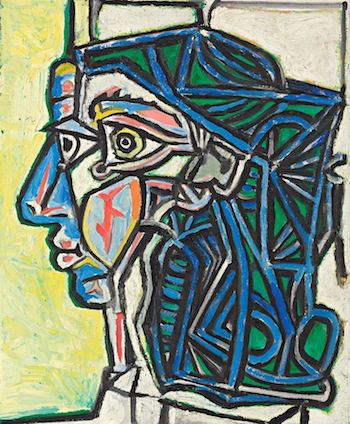

The paintings’ subjects are, for the most part, women in Picasso’s life, starting with his lover Marie-Therese whom he met during his first marriage. The liaison was already five years old when he produced the three portraits on view. In “Sleeping Nude,” a charcoal sketch from 1932, he defines her face and body in sinuous lines that, even now, feel fresh, as though the artist had just lifted his hand from the canvas. Her oval head, softly feminine in form, and spherical breasts make no secret of the artist’s obsession. Even the 1934 oil “Head of a Woman,” with its greater abstraction and harder edges, reveals how Picasso perceived her; when a flower stands in for an eye, it’s a tribute to her beauty.

Picasso was frankly subjective in his portraiture. “One paints and one draws to learn to see people, to see oneself,” he said, and his self-perceptions are on full display. So, too, are technical prowess and innovation.

Pablo Picasso, “Head of a Woman,” 1952. Photo: courtesy of the Museum of Fine Arts Boston.

Two portraits of Dora, whom he met in 1936, reveal both a distinctive female persona and an artistic evolution. In a gouache and ink drawing, Dora is bathed in light colors and covered with fine spidery lines, a technique Picasso used in many works, even in ink drawings late in his career. The picture reminds us that, as much as Picasso delved into shape and color, he never abandoned line as a primary expressive device. Here, Dora’s mouth is simply the linear outline of four triangles, two pointing up and two down, enough to show us a decided set to her mouth. Linear quality predominates again in a painting of Fernande Olivier, and in a sculpted head, where an infinite set of receding triangles defines the head.

In “Woman in Green,” Dora sits in a dark green formal dress, with puff sleeves and a rickrack collar. We feel her presence in the body’s mass and her angular face, and we suspect she is demanding something of us, and of the artist, too. The picture dates from 1944, a year after Picasso met the much younger Francoise Gilot, and it betrays Picasso’s foreboding that Dora might be less malleable than he would like.

Two portraits of Francoise, made within days of one another, make a fascinating contrast. In both, Picasso has distorted the face, placing two eyes on one side of the nose, but in the aquatint she stands at a window, and the suggestion that something lies beyond the picture frame permeates our understanding of the scene. The oil portrait, on the other hand, is confined within the single frame, but Picasso uses bold color to make her face and hair pulsate against the flat surface.

As a boy, Picasso studied classical art, sketching ancient statues and archetypal figures. As much as he later pursued innovation, his interest in historical references never waned, and he took inspiration from artists as diverse as Cranach the Elder, Rembrandt, Velasquez, Ingres, Delacroix and Manet. In the 1960s, when he undertook to depict the horrors of war, he again turned to history.

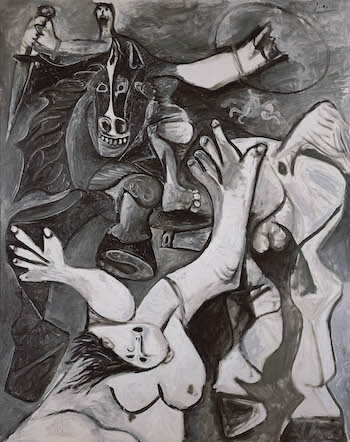

Pablo Picasso, “The Rape of the Sabines,” 1962. Photo: courtesy of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

For his two canvases “Rape of the Sabine Women”, he drew on the Romulus and Remus story of the founding of Rome and looked back across three centuries of art to study how Poussin, David, and Delacroix had depicted war. Then he used the language of twentieth century painting, much of which was his own innovation, for his work. “Guernica,” painted nearly thirty years earlier, made a strong anti-war statement, but the two Sabine paintings are in their ways no less eloquent.

Study the black and white painting and you can’t help but feel the women’s violation. A female body writhes at the bottom of the canvas, contorted beyond any logical possibilities. Her head arches back, reaching her own pendulous breasts, while a horse above lifts a hoof to stomp her into the dirt. She may be Hersilia, wife of Romulus and daughter of the Sabine leader, or she may stand in for all victims of war but, whoever she is, the impossible position of her body makes a powerful dramatic statement. That, and the paint quality. Picasso produced the work over a period of just two days, and he dashed the paint on roughly, as though he was finger painting. The texture communicates the unsettled violence of the scene.

The companion piece took a little longer to complete – twenty-two days – and derives its drama not only from the contortions of its figures but also from color. The eye is immediately drawn, again, to the bottom of the canvas, this time by the bright red cloak wrapped around the woman. Next to her stands a girl, mouth open in horror. The sexual nature of the violence is pronounced – the woman’s nipples are engorged, and so are the male genitalia above her. All the figures have rounded forms, exaggerated as though this was some sort of grotesque cartoon.

While I was looking at the two Sabine paintings, a young couple from China approached and asked if I could explain the work. They had no knowledge of art, they told me, and were confused by what they saw. What do you see, I pressed. I don’t know, the woman said, but it makes me sad and afraid. Enough said.

Kathleen C. Stone is a writer pursuing her MFA degree, a lawyer who earned her JD many years ago, and, even before that, was a student of art history. Her blog can be found here.

Tagged: Museum of Fine Arts, Pablo-Picasso, The Rape of the Sabines