Book Review: “Les Diaboliques” — An Essential Hidden Dimension in French Literature

The oft-perceptive critic Remy de Gourmont posits that Jules Barbey d’Aurevilly will “probably remain for a long time one of those singular, subterranean classics that form the real life of French literature.”

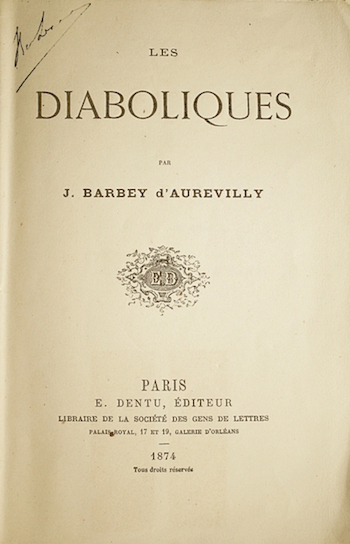

Diaboliques: Six Tales of Decadence by Jules Barbey d’Aurevilly, translated by Raymond N. MacKenzie, University of Minnesota Press, 331 pp., $18.95.

By John Taylor

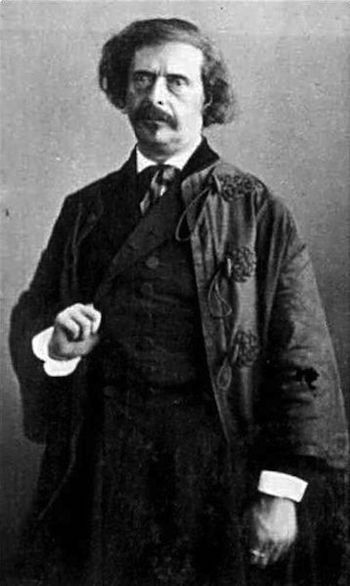

Raymond N. MacKenzie’s superb translation of Les Diaboliques (1874), the once-notorious, now forgotten collection of six “decadent” stories by the “dandy” Jules Barbey d’Aurevilly (1808-1889), is likely to go unnoticed. This would be a pity, for Barbey’s presence in French literary history is like an essential hidden dimension. Not perceiving it means missing something important about the whole.

One way of grasping Barbey’s position in French literature is to bring his friend Charles Baudelaire (1821-1867) into the picture. The latter’s equally notorious poetry collection, The Flowers of Evil (1857), explores the same social, psychological, and philosophical territory. This means sacrilege, transgression, crime, and especially “evil,” as MacKensie specifies in his Introduction, while insisting upon an important distinction: “not immorality, not wrongdoing, but evil.” The translator compares the poet and the storywriter and concludes: “The relationship between [Catholic] belief and blasphemy, God and Satan, is […] tangled and intertwined in Baudelaire and Barbey, and if its ultimate poetic expression is Baudelaire’s Fleurs du mal, its finest prose incarnation is in the stories of Les Diaboliques.”

Both the poet and the prose writer “dared to dare,” to quote (rather out of context) a remark found in Barbey’s story “A Woman’s Vengeance.” In the same tale, Barbey asserts that although “the Latin language dares to be honest, pagan that it is, [our French] language was baptized with Clovis in the font of Saint Rémy and contracted an imperishable modesty there, wearing its old woman’s blush to this day.”

The French language blushing? American readers now know what to expect from these “diabolical” tales that boldly flaunt such modesty. And readers must also expect quite a lot of crime and some misogyny. In his preface, Barbey makes it clear that the “Diaboliques” of the title are women: “Not one in this collection fails to deserve the name, at least to some degree. There is not one of them to whom one could seriously say ‘my angel’ without exaggeration.”

Baudelaire, whose view of women has also been much debated, has remained in the limelight ever since the publication of Flowers of Evil and the subsequent censorship trial for “insult to public decency.” His poetry is a fountainhead that continues to nourish French poets. Yves Bonnefoy, for example, often returns to Baudelaire in his critical essays. Poets as different as Louis Aragon, Pierre Jean Jouve, Jacques Roubaud, and Michel Deguy have likewise engaged with Baudelaire’s poetry, sometimes reacting against it. To mention one more case from among several others that could be cited, a much younger poet, Cédric Demangeot (b. 1974), has recently paid tribute to Baudelaire in his collection Une inquiétude (2013).

In contrast, Barbey’s prose, with its roots in Romanticism, Surnaturalism and la littérature fantastique, none of which were entirely foreign to Baudelaire’s sensibility, was ultimately pushed to a distant sidewalk by the procession of Realism and Naturalism. Balzac (1799-1850), Victor Hugo (1802-1855), Gustave Flaubert (1821-1880), and Émile Zola (1840-1902) ended up occupying the central avenue of nineteenth-century French prose. Most twentieth- and twenty-first century novelists have either taken off from where they left off or have attempted to counter them; only in rare cases has a contemporary fiction writer claimed to have taken much inspiration from the author of Les Diaboliques.

I do remember one exception. Way back in 1992, I participated as a critic in a panel discussion, in La Ciotat, with the novelists of the Nouvelle Fiction group: Hubert Haddad, Georges-Olivier Chateaureynaud, Marc Petit, François Coupry, Jean-Luc Moreau, and others. I recall that Barbey was favorably evoked by some of these novelists who were seeking to break away, via imaginative and speculative fiction, from what they viewed as the predominantly realistic and especially autobiographical trend in French writing.

Yet interestingly enough, as far as Realism goes, Barbey, who was also a much-feared literary journalist in his day, enthusiastically championed Balzac. In an article published in 1849, he exclaimed that the author of The Human Comedy was equivalent to “the Alps.” Even more tellingly, when Barbey prefaced Les Diaboliques, he noted that his own stories were, “unhappily, true. Nothing has been invented. The real people have had their names altered: that is all!”

He drives this realist nail home by stipulating that his “real histories” have been “drawn from this era of ours, this era of progress, of such delicious and divine civilization that when I took it into my head to write them, I felt always as if the Devil were dictating!” Above the first story, “The Crimson Curtain,” Barbey added the following single word in English as the epigraph: “Really.”

Moreover, Barbey adopts an autobiographical vantage point in nearly all his stories. Little does it matter whether they are true or not: they are meant to be read as if the author had personally witnessed them in one way or another. This autobiographical effect is established at the very onset. Here’s the first sentence of “The Crimson Curtain,” where the narrator employs very specific details showing that he knows what he is talking about: “Many, many years ago I used to go duck hunting out in the marchlands of the west—and since in those days there was no railroad in the region, I took the *** coach, which passed the crossroads near the Château du Reuil, a coach that, at the particular moment in question, was occupied by a single passenger.”

The second story, “Don Juan’s Finest Conquest,” opens with a dialogue and introduces a similarly credible “I”:

“What—he’s still alive, that old sinner?”

“Good God—still alive indeed, and by the grace of God, Madame,” I replied, catching myself as I recalled her religious devotion.

The third story, with its revelatory title, “Happiness in Crime,” likewise opens with the first-person narrator walking in the Jardin des Plantes, in Paris, with one Doctor Torty. The narrator then offers a personal memory: “When I was only a child, Doctor Torty practiced in the town of V***, but after some thirty years of that agreeable life, and when all his patients had died—his ‘tenant farmers,’ he called them, and indeed they brought in more for him than all the tenants do for their landlords throughout Normandy—at that point he decided to take on no new patients.” The “V” here is no less than Valognes, a small town long associated with the author’s family and located near the village where the author was born in lower Normandy.

Similarly, “Beneath the Cards in a Game of Whist” is set in the author-narrator’s recent past:

One evening last summer, I was visiting the Baroness de Mascranny, a Parisian woman who still loves the kind of witty, sparkling conversation that used to be in fashion, and who opens the double doors of her salon (though only one door nowadays would be more than sufficient) to the little bits of it that still exist among us. […] The Baroness is, on her husband’s side, descended from a very old and very illustrious family originally from the Grisons region. Her coat of arms is, as everyone knows, gules with three fasces, gules with an eagle displayed silver, a key silver dexter, a helmet silver sinister; the shield charged with an escutcheon azure and a fleur-de-lis or…

These excerpts suggest why it would be a pity to overlook Barbey and why, arguably, he is overlooked: his style. To our contemporary ears, this style can sound flowery, ornate, baroque. MacKenzie pinpoints what is going on: “the Mandarin, complex sentences, the ever-expanding tissue of allusion, the insistence on orality and framing devices.”

Jules Barbey d’Aurevilly — he adopts an autobiographical vantage point in nearly all his stories.

For all their intellectual complexity, the poems of Baudelaire (and those of Rimbaud and even Mallarmé) are comparatively concise; the forms they usually adopt, the sonnet for instance, of course demand concision, whatever the semantic or symbolic density of the contents. Their poetic language opens out onto modernism, whereas Barbey’s style can give the impression of looking backward toward a more mannered, affected kind of French rhetoric. Not surprisingly, Barbey was originally attracted to Baudelaire because of the latter’s translation of the stories of “le bizarre conteur” Edgar Allan Poe. It could be said that Barbey’s multilayered diction and elaborate syntax stands out in French literature even as Poe’s style — in comparison to that of his contemporaries Thoreau, Emerson, even Hawthorne — stands somewhat eccentrically apart in American literature.

Yet appearances are deceiving. There is an insightful passage about Barbey’s “sentences” in Marcel Proust’s La Prisonnière (1923). The author-narrator of La Recherche du temps perdu explains to Albertine—which is also the name of a character in “The Crimson Curtain”—how a “hidden reality is revealed by means of a material trace” in Barbey’s prose. Especially drawn to this specific story, Proust studies how Barbey uses “old folkways, old customs, old words, and singular old-fashioned trades” as a means of conjuring up the Past in general and thereby its relationship to our experience of the Present.

And why, while I was reading these stories, did I keep thinking about the intricately constructed, melodious “sentences” of Claude Simon (1913-2005), which also employ an “ever-expanding tissue of allusion”?

Let me pursue this juxtaposition a little further. Falsely associated with the New Novel, Simon is actually, at heart, a realist, an autobiographer, and a historian—rather like the “Suetonius or [the] Tacitus” that Barbey hopes, in “A Woman’s Vengeance,” will “arise among the novelists.” Often drawing on his own experiences (notably, at the onset of the Second World War), Simon focuses on how both personal and extra-personal—French, European—history is recalled, re-experienced, and retrospectively narrated. While pondering these questions, he weaves lots of details—details of “semi-consciousness” (as he put it)—into each sentence. Mutatis mutandis, something quite similar motivates Barbey’s own conception of style.

There is definitely a link between Proust and Simon. And Proust himself expressed his connection to Barbey. Is here thus a stylistic affiliation between Barbey and Simon? It occurs to me that these three writers might well form a hidden dimension that needs to be taken into account when one thinks about French literature. In contrast to the Gallic predilection for stylistic concision, for the kind of Cartesian clarity that eschews adjectives and adverbs and subordinate clauses (within subordinate clauses), Barbey, Proust, and Simon are all practitioners of the “long sentence” that attempts to accommodate, as extensively as possible, whole complexities of perception, remembering, thinking, and feeling.

In his Promenades littéraires (1905), the oft-perceptive critic Remy de Gourmont posits that Barbey will “probably remain for a long time one of those singular, subterranean classics that form the real life of French literature. Their altar is at the far end of a crypt, but it is a place to which the faithful descend willingly, while the temple of the great saints is open to the sunlight, revealing all its emptiness and ennui.” The time has come to pull back the latch on that cobwebbed door and to descend those dark, dank steps.

John Taylor’s translation of José-Flore Tappy’s poems, Sheds: Collected Poems 1983-2013 (Bitter Oleander Press), was a finalist for the 2015 National Translation Award. In 2013, he was awarded the Raiziss-de Palchi Translation Fellowship from the Academy of American Poets for his project to translate the Italian poet Lorenzo Calogero—a book that has now appeared as An Orchid Shining in the Hand: Selected Poems 1932-1960 (Chelsea Editions). He has also translated books by Philippe Jaccottet, Jacques Dupin, Pierre-Albert Jourdan, Georges Perros, and Louis Calaferte. He is the author of the three-volume essay collection, Paths to Contemporary French Literature (Transaction Publishers). His latest personal book is If Night is Falling (Bitter Oleander Press).