Theater Interview: Deborah Lake Fortson on “Body & Sold”

Everyone can work on changing the cultural values we live with. De-glamorize pimps. Work against the sexualization of very young girls.

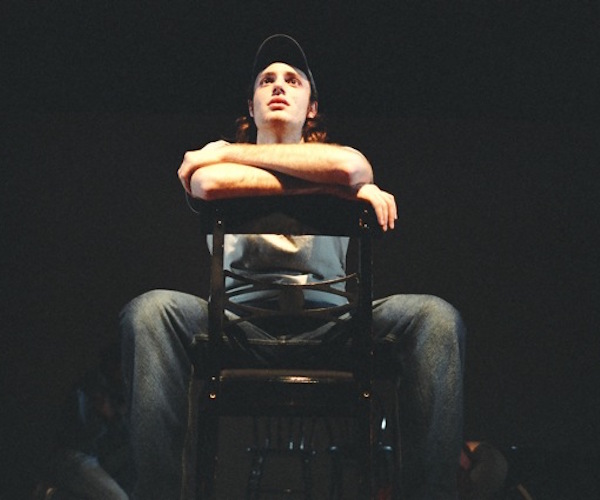

Dylan Levers as Jason in the Roxbury Community College presentation of “Body & Sold.” Photo: courtesy of Deborah Lake Fortson.

By Bill Marx

I go back with Boston-based actress/playwright Deborah Lake Fortson over 30 years. Her performance in her wonderful play Baby Steps, produced by MOBIUS, remains an indelible memory. Never has infantile regression been so transfixing. Obviously, the fragile state of innocence, and preserving it, is one of Fortson’s abiding concerns. For well over a decade, the dramatist and actress has been focusing on an ambitious, globe-trotting project that dovetails the power of the theater with a desire to combat the mounting problem of the sexual exploitation of adolescents. Her documentary play, Body & Sold, winner of a 2005 Massachusetts Cultural Council Artist’s Award, revolves around the ‘real life’ stories of teen sex trafficking, dramatizing the experiences (drawn from interviews) of eight young survivors while it explores the raw realities of life on the margins in five American cities, including Boston.

The latest staged reading of the script, co-presented by Tempest Productions/The Body & Sold Project 2015-2016, and the Maiden Phoenix Theatre Company, will be presented at 7 p.m. on February 7 at The Democracy Center in Cambridge. (The event is free, but seating is limited, so patrons are encouraged to reserve: contact @maidenphoenix.org.) Lindsay Eagle will direct. The show will be followed by a discussion about how to combat this heinous (and growing) problem with the playwright, police detectives from the Cambridge Police Department (Detective Sergeant Louis Cherubino, Cathy Pemberton) and outreach workers from Roxbury Youthworks (Mia Alvarado, Steven Procopio).

This event is part of a year-long campaign dedicated to generating discussion, via a network of activist theaters and audiences, that will drive cultural change. This is a work for the stage that is determined to make a difference. I talked to Fortson about how Body & Sold came about, whether film and video might be a more effective means to expose the horrors of sex trafficking, and whether she feels that her show is making sufficient impact.

Deborah Lake Forston. Photo: Alfred Guzzetti.

Arts Fuse: Talk about the genesis of Body & Sold — what impulse drove its creation?

Deborah Lake Fortson: The story of Body & Sold is one of many different people helping me to understand what transpires in the world of human trafficking. From my old friend, Judith Herman, who talked to me about the hidden world of prostitution (she wrote Hidden in Plain Sight and Trauma and Recovery) to the young men and women I interviewed who generously told their story in the kind of detail that makes audiences know them intimately. To the many, many people in India, Boston, Minneapolis, Brooklyn, Hartford, and L.A. who took me into their worlds.

I began to dig into the tangle of human trafficking stories when Myrna Balk. an artist and social worker, told me stories she had heard in Nepal, about girls trafficked into India. I went there and heard many stories first hand. I traveled with rescue teams to contact girls in brothels. Out of that experience I brought home texts from interviews conducted in Mumbai by the rescue agent Balkrishna Acharya and from SANLAAP in Kolkata (Calcutta). I assembled a multicultural group of actors and in 2003 we created Body & Sold: India at the Boston Center for the Arts.

After a show, Carol Gomez of Trafficking Victims Outreach, who now works for the Governor’s Council on Domestic and Sexual Violence said to me, “You don’t have to go to India to hear stories like this, you know.” I said, “Tell me.” And she told me stories she had heard while interviewing prostitutes in Minnesota for the Department of Justice. She sent me to Breaking Free in St Paul and I talked with women who had made it part of their deal with the justice system to do the twelve-week program there instead of serving time in jail. I met social workers from Off Streets, a street outreach program in Minneapolis, and interviewed boys who had been living on the streets for years.

These stories were not just about the routines and the horrors of the street life. The stories these young men and women most wanted to tell were about the difficulty and terror of growing up in dysfunctional and abusive families, and the events that led them to run away from home. And the hidden traps in seemingly benign job offers or friendly ‘gifts.’ These were buried stories that almost no one in the mainstream culture was hearing, or at least reporting on. I thought I should give voice to them; I set out to learn more.

At Roxbury Youthworks I met Sondra McCroom and Olinka Briceno and met girls at Olinka’s program, A Way Back. She let me come and meet a few girls that were working with her. I did some tutoring with them, helping with reading and vocabulary. I interviewed at Paul and Lisa in Hartford, and talked with Carol Smolenski at ECPAT (Ending Child Prostitution And Trafficking) in Brooklyn. Abe Rybeck in Boston connected me with a young man he knew working at the GLASS program in L.A.

After transcribing and sifting through all these interviews, I picked eight. I interwove the stories. Many of the incidents in these stories are similar: the narratives echo each other in the details of childhood, conflicts with adults, and running away.

The play is built around the central monologues of each character — as they told it to me, with names changed. Some parts of the stories are constructed from what I was told by social workers about young people they had worked with. The monologues are broken up and paired with parts of other stories, so the group members progress through their collective narrative together. We hear from them all about childhood, about the moment they ran away, the different version each has of meeting the man who will pimp them, the violence he or she endured, and how they finally got free again. When one character speaks, the other actors become characters in his or her story. Sometimes they act together like a Greek chorus, giving voice to their common fears, hopes, and frustrations.

Together they tell a collective story: running away from an impossible home situation; being picked up by a man who offers help and kindness, and falling in love with him; being prostituted by that guy and eventually enduring violence at his hands and the hands of the customers. They are all trapped. The stories take another turn once the survivors find ways to escape; through the assistance of social agencies they begin to rebuild their lives in the mainstream.

In 2004, Amy Merrill joined with me as a producer, and as Tempest Productions we produced Body & Sold at the Boston Center for the Arts. In 2005, the Department of Social Services commissioned Tempest to present the play in Roxbury and Chelsea. In 2006 I went back to re-interview some of the subjects to see how recovery was going, and added a new section to the play. It was then produced in thirty cities across the country.

AF: Why not make a documentary with this material?

Fortson: From experiences with my play The Yellow Dress, a script about dating violence which is performed widely in high schools, I have seen how live theater connects with audiences, especially young people, in an immediate, visceral way. Television and video programs distance the viewer. It is easy for us to dismiss the images, knowing that they can be manipulated, and hearing a narrator telling us how to react. When stories are enacted live in front of us we are more directly connected. We can feel the thoughts, the pain, and the dilemmas that those characters are feeling — because we are in touch with the voices and bodies of the actors. It is this immediate physical connection in space together that allows us to identify with the character, feel their feelings, and have profound reactions ourselves.

Young people in particular will identify with a character played by a live actor. In discussion after shows at schools, students will often say they feel the actors are the people they play in the story, even though they know objectively they are seeing performers. This close identification with the play’s characters suggests that theater is a powerful way in which we are better able to put ourselves in the shoes of others. And that means we can then ask urgent questions about how things might have turned out differently.

Live theater can make us laugh wildly, cry, be filled with fury and outrage. These are useful feelings for stirring us to social action. The Body & Sold Project wants to help generate some kind of action, to trigger activism in the audiences who will see these live shows during the year.

AF: What light does Body & Sold shed that human trafficking that TV documentaries and news programs miss?

Fortson: In movies and TV, the focus is on the trafficking and how the victims finally escape or are rescued. Sometimes there is information about follow-up programs and the heart-breaking difficulty of re-starting their lives. Action is filmed in the streets and arranged around a narrative line, with the point of view of the filmmaker.

A scene with the cast of “Body & Sold” at Roxbury Community College. Photo: courtesy of Debrorah Lake Fortson.

I think a lot of video and film productions have a tendency to flatten differences between people, to make details conform to a pre-existing idea.

In the voices of the characters in Body & Sold, I think what strikes the audience is the illuminating detail in their stories, the unique way each one of them feels and reacts, the differences in how they feel unheard and unheeded in their families, how they negotiate their escapes. Because a play of this kind is language-based and not made up of filmed ‘action shots,’ we hear each person’s unique voice, un-distracted by ‘real’ action sequences, and un-framed by narration. Each voice talking has a style that is as distinctive as a fingerprint, unique to each person.

Body & Sold highlights some topics that are minimized in TV documentaries.

1) The men and women I spoke with came back again and again to the idea of HOME. They wanted to get home. They talked about the homes they had come from that were fragmented, stifling, or frightening, and the promise of a home in the company of their pimp. Finally, they spoke about the pride of having their own place, or their own job, having their children back home with them after being held by the state.

2) Their stories of the abuse in childhood, and again in adulthood — either at the hands of their pimp, or in the context of being homeless in the midst of this ‘affluent’ society — were complex, appalling, and wrenching beyond anything I had heard before. The ins and outs of these individual stories are complex beyond any kind of fiction or arranged narrative.

AF: What are the challenges of directing Body & Sold?

Fortson: This might be a better question for those who have staged Body & Sold before, such as Robbie McCauley, who directed the show on November 1 at Charlestown Working theater, or to Lindsay Eagle, who is directing the production on February 7 at The Democracy Center in Cambridge.

When I directed it myself, I was concerned as to how to stage the violence described in the show without realism. We developed a physical theater style that made the audience feel the violence through the abruptness of the performers’ actions and the jagged sharpness of their movements. The chaotic, random violence inflicted by pimps is depicted by the actors as a chorus rampaging around the stage in falls and rolls and tumbling over objects, being suspended upside down, rather than the literally fighting or directly suggesting the intentional injuries (cigarette burns, bones breaking) that are described in the text.

Another concern is how to maintain intimacy with individual characters and the details of their stories while moving from one story to the other, weaving these distinct perspectives in and out of the sections spoken as a chorus. The answer seems to be to have really wonderful actors, who speak the text as though it were their own. We have been fortunate so far in having an abundance of these good young actors read the play.

AF: Have you been pleased with the reactions of social agencies and audiences?

Fortson: Social agencies are wildly enthusiastic about this project! It extends the work they do to educate the public about trafficked children and teens into new territory. They have had good suggestions in terms of revisions, especially when ti comes to keeping me up to date with how circumstances have recently changed. Our government institutions have become more informed and laws have been revised. Detective Sergeant Louis Cherubino of the Cambridge Police Department suggested in September that the recruitment of girls and boys has moved much more onto the internet than as it is depicted in the play. We are going to create a new scene to show that new route, with the help of officers in the Special Investigations Unit.

Audiences are always shocked by Body & Sold. They come knowing about trafficking, but even those who know quite a lot are rocked by the idea that it is happening in their city or their neighborhood. I have had people complain that the real life situations are different; for instance, that genuine street life is much harsher than what we depict. That the language would be much rougher. But we are presenting the stories as told by the survivors, and they were concerned with keeping the stories accessible and real. And we don’t want to blow the audience out of the theater with the rawness of these lives. The unexpurgated stories are available to the public, for instance in documents archived by ECPAT (Ending Child Prostitution and Trafficking). These unexpurgated testimonies are much more raw and devastating than the ones I have put in the play. I did not want to include material so horrifying that it would disgust viewers, that it would stop them from feeling and thinking in a complex way. The point is not to be sensationalistic, but the opposite — To see the everyday-ness of these situations and acts.

Emilia Richeson as Dora in the Roxbury Community College presentation of “Body & Sold.” Photo: courtesy of Deborah Lake Fortson.

AF: This new campaign — The Body & Sold Project 2016 — is dedicated to generating awareness and engagement in the Boston area. Why did you decide to create this network of theaters and readings now?

Fortson: Amy Merrill and I had been talking about reviving Body & Sold when we heard reports that there were more runaway children due to the economic downturn. Then with Occupy Wall Street and the Black Lives Matter movement, for the first time in a long time young people are camping out, lying down on bridges and gathering in stations to stage social protests. The time seemed ripe to make a more forceful stand about the sexual exploitation of American children and teenagers. To try to create activism around this issue.

AF: Who are you collaborating with?

Fortson: We’ve been working with theaters, starting with Lee Mikeska Gardner at the Nora Theatre, and Kate Snodgrass at Boston Playwrights’ Theatre. I went to Roxbury Youthworks to recruit Mia Alvarado, who worked on the 2005 event. Tempest decided to do a series of performances with discussions in different neighborhoods including police detectives and social agencies involved in this struggle. Each place we approach, there is an enthusiasm and energy to do something, to spark change. First, the Nora Theatre opened the series, then Marc Miller at Fort Point Theatre Channel, and in November —Sleeping Weazel at Charlestown Working Theater. In the spring there will be readings at Boston University School of Theatre, Boston Playwrights’ Theatre, Codman Academy in Dorchester, and Hibernian Hall in Roxbury, as well as readings in New Hampshire and Maine.

AF: Body & Sold is dedicated to generating awareness and engagement. Have you made an impact? What would you consider a successful outcome?

Fortson: Yes, we want to “raise awareness about the root causes of the problem” and “devise new strategies for prevention.”

Mia Alvarado, our wonderful collaborator from Roxbury Youthworks, always says the best action for prevention is to have a conversation with a young man or young woman you know. I would add that we would like people to have conversations with other folks who are in a position to change policy or to implement ideas for prevention. For instance, at the Fort Point reading, a gentleman asked if the play had been performed in the high schools. No, it hasn’t. That opens a role for audience members: Go to your PTA or the principal of your school and have a conversation with him about this topic, about the play, and the impact it had on you.

We learned in September that Roxbury Youthworks and the Boston Department of Education are collaborating to do trainings with faculty and staff in 2015-2016 on this topic. This is a big step: it opens the way for citizens to weigh in and ask for education and prevention programs in the schools for students.

Other actions people can take: People can mentor a child. Be a Big Brother or Big Sister. They can volunteer to tutor in the school systems an hour or two a week. The support you can give a child — as someone outside the family that has faith in him or her — can be tremendously important. Support the institutions that are doing the hard work of helping kids get off the street and re-start their lives: Roxbury Youthworks and My Life My Choice are the major ones in Boston. But there are many other groups doing some version of this work.

A group of actors and members of some of the audiences will be doing a series of POP UP performances to educate the public about detecting the signs of when a person is being trafficked. We will be performing these in train and bus stations, where this activity takes place.

Everyone can work on changing the cultural values we live with. De-glamorize pimps. Work against the sexualization of very young girls — as reflected in the clothing choices available, the emphasis on uniform and ‘glamorous’ appearance in our culture. Protest when you see Halloween costumes for a Ho and a Pimp. (I kid you not.) Protest about the lyrics in songs that encourage violence against women.

More far-reaching and difficult goals: work to change the economic structure of our system. Build more training programs for youth and develop high school programs that train kids for jobs that exist in the real world. Create more jobs for youth. Get philanthropists involved in changing the face of the cities — create urban manufacturing that will employ people where they live. Create more help for families in trouble, especially for single parent families.

And support our project! Tempest Productions, The Body & Sold Project: Tempest @rcn.com

Just start by talking about it …

Bill Marx is the editor-in-chief of The Arts Fuse. For over three decades, he has written about arts and culture for print, broadcast, and online. He has regularly reviewed theater for National Public Radio Station WBUR and The Boston Globe. He created and edited WBUR Online Arts, a cultural webzine that in 2004 won an Online Journalism Award for Specialty Journalism. In 2007 he created The Arts Fuse, an online magazine dedicated to covering arts and culture in Boston and throughout New England.

Tagged: Body & Sold, Deborah Lake Fortson, Human Trafficking, Lindsay Eagle, Maiden Phoenix Theatre Company