Book Review: The Night Bob Dylan Plugged in

Bob Dylan had been soundly booed, we heard, for playing a set plugged. What ninnies dictate the rules in the backwater world of American folk music!

Dylan Goes Electric! Newport, Seeger, Dylan, and the Night That Split the Sixties by Elijah Wald. Dey Street Books pp., 368 pages, $26.99.

Cover art for “Dylan Goes Electric!”

By Gerald Peary

Had I really been so smitten by the Kingston Trio to have purchased, late 1950s, four of their so-square albums? And, a bit later, to have genuflected to the love-thy-neighbor, soothing harmonies of Peter, Paul, and Mary? By the mid-1960s, my musical taste had toughened and hardened. So when my friend Charlie and I attended the 1965 Philadelphia Folk Festival, we cheered loudly over the jeers when the Paul Butterfield Blues Band, a haughty bunch from Chicago, strutted on stage with their electric instruments. We felt such disdain for the spineless crowd, too prissy and delicate to appreciate anything raw and real, anything other than wistful tunes played quietly, politely on acoustic instruments. More, we were angry because of what had occurred several weeks earlier in Rhode Island at the 1965 Newport Folk Festival. Bob Dylan, of all people, had been soundly booed, we heard, for playing a set plugged. What ninnies dictate the rules in the backwater world of American folk music!

I lived in New Jersey. I hadn’t actually been at Newport. Did I get it right, what went down that fateful evening of July 25, 1965? Fifty years later, I know much more, thanks to Elijah Wald’s impressively researched, authoritative Dylan Goes Electric! Newport, Seeger, Dylan, and the Night That Split the Sixties. Wald, a heralded biographer of Robert Johnson and Dave Van Ronk, admits he has never met the elusive Dylan; and Pete Seeger died in January 2014. Wald missed out interviewing him for his book. But Wald has talked to dozens of other Newport 1965 witnesses, both performers and fans in the crowd. Most important, he’s watched again and again the film record, mostly provided by documentarian Murray Lerner, of what happened at Newport 1965. Studying Lerner’s film, Festival!, including the revealing outtakes, Wald has been able to pinpoint for the reader what happened on stage, backstage, and off-stage during Dylan’s infamous 25-minute, 5-song performance.

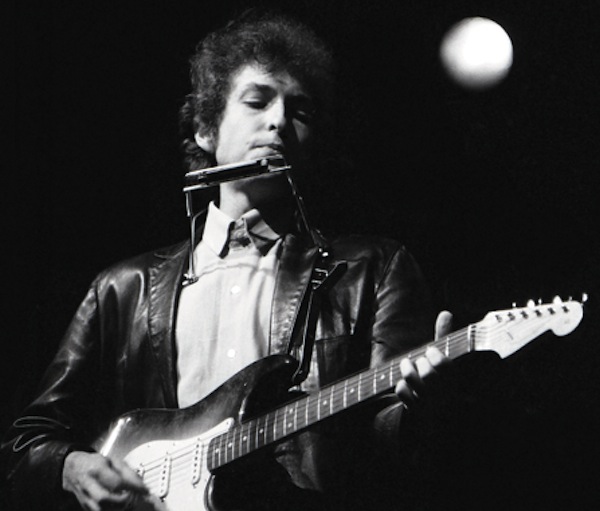

Wald describes colorfully how it began. “Bob Dylan took the stage in black jeans, black boots, and a black leather jacket, carrying a Fender Stratocaster in place of his familiar acoustic guitar. The crowd shifted restlessly as he tested his tuning and was joined by a quintet of backing musicians. Then the band crashed into a raw boogie and, straining to be heard over the loudest music ever to hit Newport, he snarled his opening line, ‘I ain’t gonna work on Maggie’s Farm no more!’” Through a three-song set (also “Like a Rolling Stone” and “Phantom Engineer,” an in-progress version of “It Takes a Lot to Laugh, It Takes a Train To Cry”), Dylan ploughed on, electrified and dissonant and incredibly noisy, backed by an all-star ensemble of rockers including pianist/organist Al Kooper and, borrowed from the rowdy Butterfield Band, guitarist Mike Bloomfield and drummer Sam Lay. Then Dylan & company left the stage. After several minutes, Dylan returned solo, with a Gibson guitar. He tuned for many more minutes without talking to the audience, then offered a two-number encore. If there was a slight concession to the majority wants of the crowd, it was Dylan reprising a favorite from earlier Newport Fests, “It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue.” Exit Bob Dylan.

The tunes with his improvised band were woefully unrehearsed, the recruited bass player, Jerome Arnold, was at sea in keeping proper rhythm. Guitarist Bloomfield seemed to take sadistic pleasure in aggressive, punishingly shrill solo riffs. Though the songs weren’t played very well, some in the crowd wildly applauded, like I did at the Philly Folk Fest, welcoming an electric rock ’n’ roll future to staid Newport. But many in the audience did indeed boo. Who was this wayfaring stranger on stage? They wanted acoustic Bob. They wanted political Bob who, at Newport 1963, had sung “Blowin’ in the Wind” and “We Shall Overcome,” flanked by Pete Seeger, the Freedom Singers, Joan Baez, and Peter, Paul, and Mary. It was OK for the folk-rock Byrds to do an electric version of Dylan’s “Mr. Tambourine Man,” wildly popular in 1965. But the songwriter himself should strum away unplugged.

Might the audience have been clued in that Dylan had changed? In March 1965, he released the album, Bringing It All Back Home, with an electric side and an acoustic side. In April 1965, he issued a single of “Subterranean Homesick Blues,” with, says Wald, “its rocking rhythm and Chuck Berry-style vocal making it the first Dylan record to get pop radio play.” “Like a Rolling Stone” — thrillingly electric, featuring Al Kooper’s hooky pumped-up organ — was released just before Newport as a 6-minute ‘45, the longest single ever. Had anyone read a spring 1965 interview in which Dylan clearly stated the shift in his aesthetics: “I’d rather listen to Jimmy Reed or Howlin’ Wolf, man, or the Beatles…than I would listen to any protest song writers.”

On that night, the Newport Folk Festival was “Maggie’s Farm,” as Dylan declared he “ain’t gonna work” by Newport’s imprisoning strictures. Fie on acoustic instruments only! Fie on not freaking out the gentle, peace-abiding audience. Wald explains,, “Everyone had gotten used to being affirmed and comforted at Newport….That sense of warmth and community, of leaving differences at the festival gate and joining in musical fellowship was not Dylan’s style. …Dylan had looked the community in the eye and gunned it down in cold blood.”

Someone in the crowd joked that Dylan “electrified one half of his audience and electrocuted the other.” Alan Lomax, the legendary collector of folk songs and discoverer of folk singers, and gatekeeper for traditional Newport, huffed that Dylan “more or less killed the festival all in motorcycle black in front of a very bad, very loud, electronic r-r band….That boy is very destructive.” And what of troubadour Pete Seeger, the spirit and conscience of the Newport Fest, who in contrast to Dylan, “…was everywhere: singing, playing, and giving encouragement to old rural musicians and young songwriters alike”? Seeger, a longtime admirer and booster of Dylan, was horrified by the spectacle on stage. He who prided himself on the modesty of his singing and banjo playing was rattled by the deafening, arrogant sound of Dylan’s ensemble.

Through the years, a story has persisted, that the famously pacifist Seeger ran wild backstage trying to find an axe to cut the cables and turn off the electricity on Dylan’s set. Wald investigated and found no evidence of Seeger seeking an axe. Seeger’s own version of what happened, written a few days later, seems as credible as any offered: “I ran to hide my eyes and ears because I could not bear either the screaming of the crowd nor some of the most destructive music this side of hell.”

This was neither the first nor last time that Dylan’s on-stage antics upset the gathered. Early in his book, Wald takes us back to 1957 in Hibbing, Minnesota, where 16-year-old Bobby Zimmerman grossed out a high school audience and rankled the principal with his anarchic, ear-splitting rock ’n’ roll playing. A school friend remembered: “I guess Bob lived in his own world, ‘cause apparently the audiences booing and laughter hadn’t bothered him in the least.” Later in 1965, as Dylan played on electrically at concerts after Newport, he got used to a hostile reaction from part of each crowd. He became indifferent to it. That’s the Dylan who has persisted for half a century: going obsinately his own way, supremely disinterested in what others think of him.

Curiously, that’s not what happened at Newport 1965. When Dylan exited the stage, some heard him ask with concern if anyone had seen Pete Seeger, and what did Pete think? He seemed stunned that he’s been booed, didn’t get why at all. Later, he stood by himself at a festival party, forlorn and perplexed. And this is amazing to me: the self-sufficient Bob Dylan, he often impervious to human feeling, sat down on the lap of Betsy Siggins of Cambridge’s Club 47. Seeking a maternal hug? Seeking validation for being a bit of a punk that evening on stage? Siggins told Wald in 20l4: “He did not say one word…He seemed to be exhausted, kind of overwhelmed, and it was just like I was his chair.”

Gerald Peary is a professor at Suffolk University, Boston, curator of the Boston University Cinematheque, and the general editor of the “Conversations with Filmmakers” series from the University Press of Mississippi. A critic for the late Boston Phoenix, he is the author of 9 books on cinema, writer-director of the documentaries For the Love of Movies: the Story of American Film Criticism and Archie’s Betty, and a featured actor in the 2013 independent narrative Computer Chess

Tagged: and the Night That Split the Sixties, Bob-Dylan, Dylan Goes Electric! Newport, Elijah Wald, Newport

Great piece. Although Dylan may have been “used to” hostile reactions, I don’t think he’s ever been indifferent to it. He seems to have always been hyper-aware of every criticism leveled at him. Read his comments on the Grammy awards a couple of years ago, where he addresses specific criticisms of his singing and writing, and also takes some shots at fellow songwriters. Despite his profound independent streak, he’s like any performing artist: he wants an audience, and he’s sensitive to its response.