Classical CD Reviews: James MacMillan conducts Vaughan Williams, MacMillan, and Britten and Boston Lyric Opera’s “Clemency”

Two recent albums feature compositions by James MacMillan, one of Europe’s leading composers, as well as an opportunity to hear him conducting.

By Jonathan Blumhofer

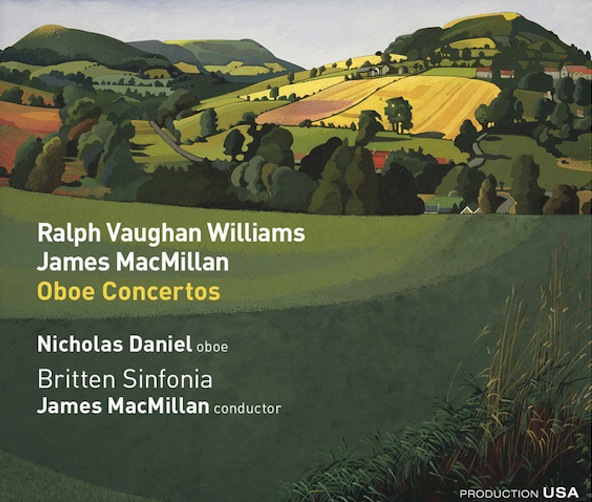

Here’s a disc that does just about everything right. Aside from Richard Strauss’s concerto, there isn’t much concerto literature for the oboe in the repertoire (certainly not from the last seventy-five years). But Harmonia mundi’s fine new recording of oboe concertos by Ralph Vaughan Williams and James MacMillan offers two great pieces that ought to be widely played and (one hopes) increasingly found on concert programs.

Musically, there really aren’t many surprises to be found in Vaughan Williams’ Oboe Concerto, though that’s not a bad thing. The score is couched in the familiar, filled with the folk-inflected, modal-ish melodies and harmonic progressions with which Vaughan Williams’ name is usually associated. But, in stark contrast to his increasingly gloomy late music (the Oboe Concerto dates from 1944), its mood is often light and genial; in that it has more than a little in common with its composer’s Fifth Symphony.

Soloist/conductor Nicholas Daniel handles the score’s rapidly unfurling filigrees with ease and plumbs the depths of its sumptuous lyricism with great care. The broad song in the second half of its finale is beautifully played, and the middle movement comes across lithe and perky. The Britten Sinfonia accompanies fluently and with a kind of refined, rustic energy.

The other big piece on the disc MacMillan’s Oboe Concerto. Premiered by these forces in Birmingham in 2010, it marries MacMillan’s love of folk sources with his penchant for sprightly rhythms. The Concerto’s snappy outer movements alternate thumping orchestral patterns with high-flying (sometimes very songful), virtuosic passages for the soloist. The slow middle movement, which began as a response to the September 11th attacks, features some of MacMillan’s most affecting, direct music to date and it’s almost a pity the mood is interrupted by the jaunty (and rather goofy) opening of the finale. Still, it’s a touching, powerful respite well worth revisiting.

Again, oboist Daniel is in terrific form, navigating the Concerto’s demanding writing with ease, more than once reminding of a skilled racecar driver hugging the inside of the track. MacMillan, an able conductor of more than just his own music, ensures an attentive accompaniment from the Sinfonia.

For filler, MacMillan leads the Sinfonia in a vigorous realization of its namesake’s Suite on English Folk Tunes: “A Time There Was…” and an absorbing account of his own One. True to its title, the latter takes a single melodic line and passes it through the orchestra, transforming it as it goes through an array of timbres and instrumental combinations. It may not be the deepest thing MacMillan’s written, but it’s an essay in subtle orchestration and bewitching to the ear.

So, too, is Britten’s Suite, his last completed orchestral composition. MacMillan’s performance captures the naturalness of Britten’s adaptations of his folk sources while also mining the nostalgia that lives not far beneath the music’s surface.

*****

Composer/conductor James MacMillian. Photo: Philip Gatward.

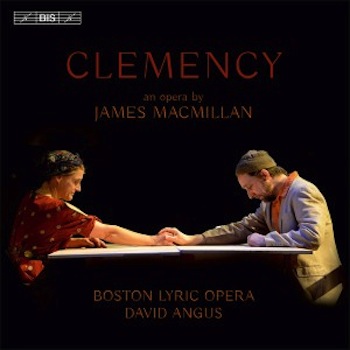

What to make of Boston Lyric Opera’s (BLO) recording of MacMillan’s Clemency (co-commissioned by the company, along with the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden; Scottish Opera; and the Britten Sinfonia)? In many regards, the opera itself is rather odd. Taking the biblical tale of the three men visiting Abraham as he sat under the oaks of Mamre in Genesis 18 and loosely adapting it to fit the present day, the libretto raises more questions than it answers. Perhaps that’s its point. Who these men are, where they’ve come from, and why they’re here is never fully explained or answered. And the tension of that mystery is felt throughout Clemency.

BLO’s staging of the piece in 2013 (from which the present recording was taken) ruffled some feathers with its depiction of the visitors as terrorists wearing vests of explosives. This new recording was drawn from those live performances and, while it necessarily doesn’t resolve the visual/dramatic issues the staging presented, the opportunity to focus solely on the music is welcome. And the one (musical) problem from the production that it does clarify is answered straightforwardly and decisively: “Hagar’s Lament,” Franz Schubert’s early song for voice and piano, has no place in this opera.

Musically, wedging the Schubert into Abraham’s opening cadenza sounds unnatural: Schubert’s style simply doesn’t juxtapose well or easily with the type of music with which MacMillan has filled Clemency. Dramatically, too, it doesn’t make any sense, because 1) the episode where Abraham banishes Hagar to the desert doesn’t turn up in Genesis until chapter 22 – three after the plot of Clemency takes place – and 2) it holds up the action of the opera. Worse, nobody needs to hear a 15-minute long Schubert lied just as a (short) new opera by one of Europe’s leading composers is about to get underway.

If it were sung in the original German, not in David Angus’s trite English translation, and without his rather haphazard “orchestration” of the score (with string supplementing the piano from time to time), perhaps some of these offences would be dulled. As it stands, even Michelle Trainor’s beautiful singing of the Lament — and you could hardly ask for a finer sense of diction, quality of tone, or purer intonation than she delivers — doesn’t justify this heavy-handed effort in attempting to provide more context to the story. On the contrary, the more one thinks about it, the less sense it makes and the more it seems like a misguided effort in political correctness.

With Clemency itself, MacMillan has crafted a short opera that, despite a few bothersome ticks (like its often-awkward settings of librettist Michael Symmons Roberts’ text), succeeds well as a work of drama. Its weird story ensures that Clemency’s focus is tight and its moral clouded in ambiguity. MacMillan’s melodic writing is colorful and, if not exactly tuneful in the manner of Mozart or Puccini, often alluring. The big diatonic landing points — particularly the moments for the Three Travelers and Sarah’s closing aria — are like oases in the desert. Personally, I wouldn’t have minded hearing throughout the opera more of the lyrical type of writing MacMillan gives Sarah in the closing section, but that’s a small complaint. He uses the string orchestra well, drawing from it a range of colors.

Cover art for the BLO recording of “Clemency.”

As far as the recording goes, I wasn’t a huge fan of Christine Abraham as Sarah. She sounded thin in her upper range and forced in her lower register. That said, her technique was more or less solid and her intonation secure, though I imagine that a singer with a bigger voice would have made (and left) more of an impact in the role. David Kravitz’s Abraham fared better: he was suitably stentorian and patriarchal, though increasingly distressed as the character considered what his guests might be up to next. And those Travellers — sung by David McFerrin, Neal Ferreira, and Samuel Levine — were appropriately mysterious. MacMillan gives the three of them plenty of winding, melismatic writing with which to work, and it suits the trio well: together, they sang with a collectively warm tone and delivered a vocally persuasive account of their enigmatic roles.

David Angus conducted the strings of the BLO Orchestra. Tempos moved at a good clip and pacing never really lagged. But the orchestra’s performance left something to be desired. There was consistently spotty intonation and the extremes of dynamics and expression that MacMillan’s score calls for were rarely, if ever, realized as intensely as they could have been. That said, the music’s overall shape and gestures came across with a kind of general clarity, though there’s never the sense that, ultimately, BLO’s is a definitive recording of this piece.

And that’s a shame. BLO’s itinerant Opera Annex productions (of which Clemency was one) offer the company its best opportunities to shine (as demonstrated in their marvelous staging of Frank Martin’s The Love Potion last fall). Co-commissioning and producing Clemency was a big step for the company and, while you do get some sense of the quirkiness and adventure of the undertaking on this disc, it’s marred by the sort of ham-fisted problems that often complicate BLO’s main stage productions, namely poor staging choices and uneven performances from singers and orchestra. I came away from this album wanting to hear more MacMillan, generally, and to have another go at Clemency, in particular, on stage; that said, I had hoped for more from this disc.

Jonathan Blumhofer is a composer and violist who has been active in the greater Boston area since 2004. His music has received numerous awards and been performed by various ensembles, including the American Composers Orchestra, Kiev Philharmonic, Camerata Chicago, Xanthos Ensemble, and Juventas New Music Group. Since receiving his doctorate from Boston University in 2010, Jon has taught at Clark University, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and online for the University of Phoenix, in addition to writing music criticism for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette.

Tagged: Benjamin Britten, Boston-Lyric-Opera, Clemency, Harmonia Mundi, James MacMillan, Nicholas Daniel