Visual Arts Review: The Erratic Eroticism of Francesco Clemente’s “Encampment” at MASS MoCA

It is a conundrum for the critic: is the crudeness of the rendering the result of an expressionist style or a lack of finesse or skill in rendering?

Francesco Clemente: Encampment at MASS MoCA, North Adams, MA, through January 1, 2016.

Francesco Clemente, “Standing with Truth Tent,” 2012-2013 (interior view). Tempera on cotton, embroidery, hand stitching, bamboo poles, wood finials, ropes, iron weights. Photo: Courtesy of MASSMoCA.

By Charles Giuliano

Francesco Clemente (born in Naples, March 23, 1952) emerged in the 1980s with the Neo-Expressionist movement. His work, along with that of fellow Italians Enzo Cucchi and Sandro Chia, were acquired in depth by the British collector Charles Saatchi. The collector/ speculator later liquidated their work, flooding the secondary market, which damaged their reputations.

While Cucci and Chia have fallen off the radar screen, Clemente, through reinvention and extensive travel between studios in New York and India, remains in the spotlight. This exposure at MASS MoCA underscores his unique staying power.

The exhibition comprises three elements: extensive installation of decorated tents, four similar sculptures in the dark gallery under the overhang, and a series of current collage/ watercolors above. From a landing leading to the 30,000 square foot gallery of Building Five we see a cluster of six, brightly colored tents which make up Encampment. That initial vantage point with its sweeping overview is followed by closing the gap in what curators refer to as “the approach.” As with musical rests, the empty space leading to and surrounding the works is a part of the visual composition.

When, prior to development of the museum, Tom Krens walked me through the 17 acre complex of buildings that made up the former Sprague Electric Company, there were two floors in Building 5. As he explained, the second floor would be removed, creating one of the largest galleries for contemporary art in North America. Others are Dia Beacon in upstate New York and the Chinati Foundation in Marfa, Texas.

There have now been a number of one year installations in Building 5. In general, the glass has been half empty or half full. The aesthetic response focuses either on the container — that vast industrial-scaled space — or what is contained. The most successful installations have been specifically designed for this distinctive gallery. Or, as is the case with Clemente, large works predated the decision to install them in Building 5.

A litmus test is the degree of our awareness of the surroundings while navigating the work. In this case the synergy is questionable.

Francesco Celemente, “Tents,” an installation view. Photo: Courtesy of MASSMoCA.

When I first encountered the tents at Mary Boone Gallery they aroused interest for several reasons. My first impression centered on the tentness of the tents. What kind of associations do tents arouse? The range of signifiers spun out included shelter, nomads, caves, places for camping, retreat, meditation, rituals, and religions. But these primal associations are short-circuited by the installation’s artificiality. The norm is to think of a tent as erected outdoors. Routinely, poles and ropes support fabric structures by attachment to the ground with stakes. Here they are tethered by large metal blocks. These tents have been erected not in nature but in an industrial landscape. There is a scuffed up surface of cracked concrete instead of earth, grass, or sand.

The exterior surfaces are decorative and hand embroidered. They are not intended to endure the elements, so the elemental functionality of a tent is denied, These are tents as metaphors, figures of visual poetry, forms of an exotic but very much westernized Orientalism. The tents evoke the East, but the simple, aqueous, and broadly depicted figurations on their surfaces suggest an artist that is very much rooted in the traditions of the West.

The painterly style of Clemente suggests works by the German Expressionists Emil Nolde and Karl Schmidt-Rotluff. They also channel fellow Italian Carol Rama, who is known for her fluid, brushy erotica. The similarity of her work to Clemente’s is uncanny, although her art is personal, small in scale and eccentric.

In the press release the artist states that the works “were generated by reflection on my own life, and my own needs; it was as if I didn’t have a home, but wanted one.”

All six tents are being displayed together here for the first time. (They were created from 2012 through 2014, in collaboration with a community of artisans in Rajasthan, India, who crafted large 2-pole structures, measuring some 10’ x 18’ x 12’ high.) Entering the first of the series of tents/ rooms makes one think of the Magic Theatre of Herman Hesse’s Steppenwolf. Each tent has a unique theme; some are explicit and others are not.

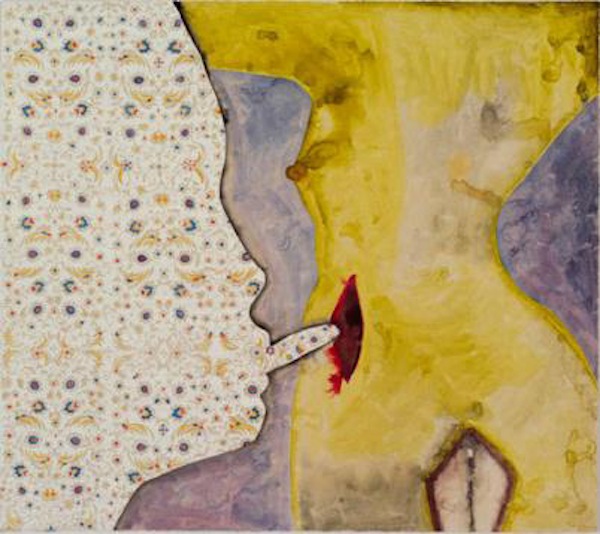

Francesco Clemente, “No Mud, No Lotus 13,” 2013-2014, Watercolor and miniature on handmade paper. Photo: Courtesy of MASSMoCA.

Entering a space filled with images of angels, we identify a version of Icarus as well as a crouching, tucked-up winged figure sporting a rather large erection. There are many erotic references throughout the exhibition, including the array of watercolors from the No Mud No Lotus series.

If we approach the six spaces as meditations, it is difficult to find a connecting ideas. There are discernable vignettes. A gentleman with top hat and monocle signifying a billionaire is engaged in aspects of slavery and rampant capitalism; a dog on a leash evokes an S&M scenario. The Museum tent riffs on a series of crude but evocative self portraits — skeletal renderings set in ornate frames. One of the images shows the artist with his tongue hanging out — he is being hanged by the neck.

The style of figuration is flat, generic, and non-descriptive. The flatness makes one want to use the term linear, but they don’t deserve being compared with the crisp lines of Gauguin or Matisse. It is a conundrum for the critic: is the crudeness of the rendering the result of an expressionist style or a lack of finesse or skill in rendering?

Interviews and statement from the artist are not helpful in this regard. He tends to discuss the work obliquely, deftly reflecting direct questions about process and intentionality. While he generates guru-like vibes, Clemente doesn’t send an easy-to-get message.

For the four sculptures Earth, Moon, Sun, and Hunger a jungle like, tower of sticks and support platforms containing different elements — a banner, large metal box, gilded boom box and a round metal vase with branch like tendrils. The banner on one side has an embroidered quote from Guy Debord: “the spectator feels at home nowhere because the spectacle is everywhere.”

The small works on paper continue his ventures into the erotic, including images of a woman penetrated front and back. There is also a large tongue licking a womb or wound.

Charles Giuliano, Founder/Publisher of www.berkshirefinearts.com, an art historian and former writer/critic/editor for Art New England, The Boston Herald Traveler, Boston After Dark, The Avatar, and The Patriot Ledger. He taught at New England School of Art at Suffolk University, Boston University, Salem State University, UMass Lowell and Clark University.

Tagged: Charles Giuliano, Encampment, Francesco Clemente, Italian, MassMOCA