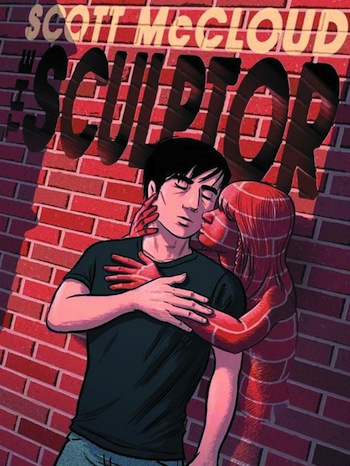

Book Review: Scott McCloud’s “The Sculptor” — A Life in His Hands

A graphic novel about the death of art and the art of death

The Sculptor by Scott McCloud. First Second, 495 pages, $29.99.

By Milo Miles

A reviewer ought to immediately confess the perceptions and attitudes that will annoy and even appall the artist under discussion, because then the interaction can only get brighter. In theory.

The lede in graphic artist Scott McCloud’s obit will note that he created Understanding Comics in 1993, the most cogent, penetrating and thorough study of the history, mechanisms, and artistic language of equal-words-and-pictures stories. The follow-up volumes, Reinventing Comics (2000) and Making Comics (2006) are nearly as fundamental. But all that’s for the straights. For twerps like me who have thousands of comics in bags and boxes and special last-through-the-apocalypse storage containers, the Scott McCloud comic closest to the heart is the series Zot!, first published in 1984 when he was 23.

McCloud is right to metaphorically roll his eyes every time somebody gushes about Zot! No one likes to be told their first shot was their finest. And that’s not what I’m saying. Zot! was simply a cry of joy and affirmation of the comics medium that came along at exactly the right time, when the vigilante Batman and the unfettered gun-nut the Punisher were on the rise and mainstream comics were headed toward a more callous and reactionary future than they had ever known. The Zot! section of McCloud’s website will fill you in on the specifics of the book. Of course I am most fond of the first 10 issues that appeared in color.

So much for annoy. Let’s move on to appall. Since the climax and decline of Underground Comix in the late ‘60s and early ‘70s, there have been two innovative (rather than regressive) developments in comic-book narrative. The first began in 1972 with Justin Green’s landmark, Binky Brown Meets the Holy Virgin Mary, the story of a youngster’s epic tussle with Catholicism that showed how graphic storytelling could release the freaky subjective side of autobiography. This style has been mostly liberating for the field, though plenty of tedious life stories are around as well. The other development is what I call “domestic-realism graphics,” which began with master strip cartoonist Will Eisner’s Contract with God in 1978 but found its most popular early flowering in Gilbert and Jaime Hernandez’s long-running series Love & Rockets (started 1981). No accident that Eisner gets credit for coining “graphic novel” to refer to his later works, though now it has become generalized to apply to any book-length comic.

I do not think domestic-realism graphics are unimportant or untalented. But I do find the style uninvolving compared to other comic modes … and maybe even a shade unnecessary. I dropped out of Love & Rockets during the ’80s when it struck me – “is there any real reason this is words and pictures instead of plain prose, which might do a better job of it anyway?” McCloud and I are not on the same page about the qualities of domestic realism, judging from his selection of “Great Comics Are Not a Genre” in The Best American Comics 2014 R. Crumb and Aline Kominksy and the unearthly Charles Burns are indeed Greats. As is the boundary-buster Chris Ware in a different section. The Hernandez Brothers belong in somebody else’s museum, not mine. Ben Katchor, someplace in between.

Obvious strains of domestic realism penetrated the later, black-and-white issues of Zot! The pace slowed. The energy dropped. I never finished what had begun as my favorite all-ages comic in many years. No doubt, the big general question hanging in the air about McCloud’s The Sculptor was — can the grand theorist produce grand artwork? For me, it was – how much is this going to be hobbled by domestic realism?

Helps that McCloud is gifted at depicting isolation and loneliness. Young sculptor David Smith (the ordinariness of the monicker is a motif) has tragically lost all of his immediate family and now struggles to make a name for himself, as his late father requested, in what seems like late-’90s New York City. McCloud is as good as anybody at filling silent panels with sadness. David’s fickle patron has recently dumped him from the gallery circuit and he can’t quite trust his oldest friend, so it’s a joyful surprise when, as he’s getting hammered in a café, he runs into his Grand Uncle Harry. And even he’s Death in disguise.

As many have noted, being Death is a depressing job, so every few thousand years the Reaper amuses himself by living a human’s life after their mortal self dies young. Uncle Harry has been Death since David has known him. Indeed, Harry the regular human has been deceased for a while. Death has come back in his form to do a little Faust trip with David. The sculptor wants to realize the acme of his abilities no matter what, so Death grants him the power to mold stone and metal directly with his hands, eventually tons of material with just his imagination and gestures. In exchange, David has only 200 days to live.

An image in Scott McCloud’s “The Sculptor.”

As usual with these terminal bargains, disasters and complications come thick and fast the minute the subject agrees to the setup. David’s first attempts at sculpture are destroyed in an accident or confiscated by his landlord who throws him out on the street. In short order he meets a savvy, manic-depressive aspiring actress named Meg and they convincingly fall in love. McCloud has some trouble with this central relationship. Meg and David are charming and rife with specific, finely observed behaviors and passions. But they are not seductive, captivating – you don’t fall in love with them yourself. The characters are easily overwhelmed by uncle Harry’s Death, for instance.

The Sculptor flies higher when it takes up a generally tougher subject: the nature of art and the meaning of artistic success. McCloud’s single most brilliant stoke is to make David neither a hack nor a genius. He’s got fine talents, somewhere in the upper middle of the pack, and he has to find a way to use his supernatural powers to satisfy himself and history with what skills he has. By adopting some techniques from the graffiti underground, David not only manages to become sensational without selling out, but wanted by the police as well. After numerous internal upheavals, he takes the risk of sharing his unworldly situation with Meg. And when you are literally counting the days, events accelerate toward a climax that comes with a couple hardboiled twists. (McCloud also leaves two unanswered mysteries, one a haunting intrigue, the other an unsatisfying annoyance. Both contain spoilers.)

McCloud long ago abandoned inks and brushes in favor of sketches, computers, and Photoshop to create his graphics. I used to feel some vitality had been lost with this change, but when I dug out the original run of Zot! and did some comparing it turns out the new mode is neither better not worse, just different, with a far greater maturity of pacing. As you might expect, his understanding of the comics medium remains second to none. The Sculptor breaks away from realism frequently and thoughtfully enough to avoid the why-isn’t-this-prose problem. McCloud also underscores graphic aspects others still neglect – the murk of night, especially in urban backways, the torrential confusion of heavy rain. Finally, there is a multi-page sequence of wordless images, a kind of collage, at the climax of the story that has to be moving and technically powerful. McCloud nails it. You may not be in love with David Smith, but you care enough about him at that moment.

So no question – The Sculptor is very much the grown-up work of the youth who thrilled with Zot! This one I will re-read many times.

Milo Miles has reviewed world-music and American-roots music for “Fresh Air with Terry Gross” since 1989. He is a former music editor of The Boston Phoenix. Milo is a contributing writer for Rolling Stone magazine, and he also written about music for The Village Voice and The New York Times. His blog about pop culture and more is Miles To Go.

I have to agree with you, Milo. Having reread the Zot! omnibus that was reprinted several years ago, I found that my excitement dropped off when McCloud shifted from his sci-fi super heroic trappings into domestic (and high-school) realism — which, while it eschewed the grim and gritty style that so many of his contemporaries were adopting at the time, still seemed to be emblematic of how young writers (and audiences) often mistake pessimism for realism. Meanwhile, the earlier works seemed to be working towards an abandoned metafictional celebration of imagination along the lines of what Grant Morrison has done in his more mainstream work.

Of course, the other question you pose, is an important one: Will Eisner and Alan Moore have both been able to balance out their theoretical work on comic art while still being productive storytellers within the medium — yet outside of a few on-off projects, McCloud has been on a nearly quarter century hiatus while theorizing.