Fuse Remembrance: A Tribute to Albert Maysles

Albert Maysles once said: “I don’t see, frankly, trying to make a film to create better understanding. Our motivations for making films aren’t intellectual ones.”

By Tim Jackson

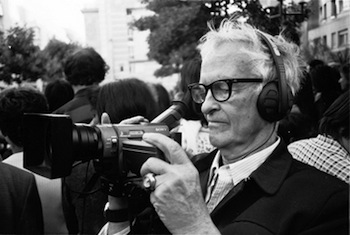

The late Albert Maysles — he was a gentle, elusive presence behind the camera.

The death of Albert Maysles at 88 this week offers an opportunity to praise his valuable contribution to American culture and to look back at the spirit and delight found in his work. Along with Robert Drew, Richard Leacock, D. A. Pennebaker, and Frederick Wiseman, Albert and David Maysles and other cinéma vérité filmmakers eschewed the manipulative strategies that were an important part of making journalistic, polemical, and propagandistic non-fiction films in the 1950s. In the early ’60s cameras became smaller and more economical and recording became less intrusive. A new approach to documentary film — called direct cinema and cinema vérité — embraced a more observational approach. Each of the directors mentioned above nurtured their own style and purpose within ‘observational’ parameters. Fortunately for us, Pennebaker and Wiseman are still creating wonderful films.

Whereas direct cinema consciously avoids the presence of the filmmaker, in cinéma vérité he or she is often a major part of the narrative dynamic. As a team, the Maysles Brothers were expert at both styles, and that is one of their strengths. Albert Maysles’s gentle, mostly unseen presence is felt in their best work. He established an obvious trust with his subjects even when his presence is not noticeable. In their masterpiece Salesman (1968), the Maysles Brothers followed door-to-door Bible salesmen around Boston. The camera is a constant companion: at motivational meetings, in and out of hotels, at private homes and apartments. That kind of access requires an engaged and secure relationship with the subjects of the documentary. Their best-known film is the classic Grey Gardens (1975), which generated a Broadway musical and a TV film about its making starring Drew Barrymore and Jessica Lange. A second film, The Beales of Grey Gardens, followed in 2006. The original film profiles the Beales, a mother and daughter, former socialites and cousins of Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy, who at the time of the filming were living in squalor in the Hamptons. In some of the best clips Edith Beale flirts with Albert Maysles, who is behind the camera. Maysles confessed that Edith had a bit of a crush on him. This added charm to her eccentric ‘performance.’

Director Werner Herzog has impugned the direct camera approach, claiming that it is somewhat false because seeing the hand of the filmmaker is the only way toward reaching an “ecstatic truth.” But Albert Maysles once said: “I don’t see, frankly, trying to make a film to create better understanding. Our motivations for making films aren’t intellectual ones.” Maysles wanted us to look closely at subjects who were encouraged to speak for themselves, free of defensiveness and the baggage of celebrity. The Maysles’s films are remarkable social artifacts. The subjects really don’t matter — The Rolling Stones, Bible salesmen, or one of their many portraits of artists — each was treated with respect and a yearning for discovery. Marguerite Duras wrote that “the art of seeing has to be learned.” Despite his enormous influence on generations of filmmakers, I have the feeling Albert Maysles never stopped learning.

I would recommend two of Albert Maysles’s less familiar short films as compelling examples of his gift for focusing on the best of humanity: Meet Marlon Brando (1965) features the actor commanding some press conferences with great wit and charm; The Love We Make (2011) presents Paul McCartney getting ready for a post 9-11 benefit concert in New York City. Both documentaries are available on Amazon and Fandor.com.

Tim Jackson is an assistant professor at the New England Institute of Art in the Digital Film and Video Department. His music career in Boston began in the 1970s and includes some 20 groups, many recordings, national and international tours, and contributions to film soundtracks. He studied theater and English as an undergraduate and has also has worked helter skelter as an actor and member of SAG and AFTRA since the 1980s. He has directed a trio of documentaries: Chaos and Order: Making American Theater about the American Repertory Theater, and Radical Jesters, which profiles the practices of 11 interventionist artists and agit-prop performance groups. His third documentary, When Things Go Wrong, about the Boston singer/songwriter Robin Lane, with whom he has worked for 30 years, has just been completed. He is a member of the Boston Society of Film Critics. You can read more of his work on his blog.