Book Review: “Silver Screen Fiend” — A Remembrance of Movie Madness Past

Why did Patton Oswalt submit himself, for a time, to drowning in movies? I never quite understood that. It had some connection with him wanting to direct cinema, and some very tenuous relationship to his comedy career.

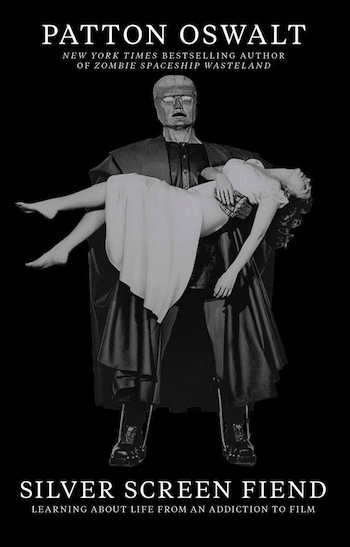

Silver Screen Fiend: Learning About Life from an Addiction to Film, by Patton Oswalt. Scribner, 240 pages, $25.

By Gerald Peary

These days, Patton Oswalt is a headliner comedian and the quirky star of two excellent, much-underrated indie features, Big Fan and Young Adult. He’s also beloved for providing the voice of Remy, the culinary rat lead in the animated classic, Ratatouille. Away from show biz, he’s married to writer Michelle McNamara, and they have a daughter. Silver Screen Fiend is Oswalt’s breezy, amusing memoir of a far shakier time in his life, 1995-1999, when he was single, unknown, and obsessed about becoming a comedy star.

He’d moved west in 1992 from the DC area, where he had some reputation as a comedian, and believed his material would succeed anywhere. A day after arriving in San Francisco, he sashayed into the hipster Holy City Zoo club to “announce myself as the new gunslinger in town.” He had a host of zippy jokes and banter, ending with a never-fail routine positing “what if the Cookie Monster was gay”? As you might figure, Patton Oswalt got his comeuppance. Nobody laughed. His mouth dried, his rhythm got off, a story about having a hernia operation sputtered, and even a line that NEVER failed—“TAMPAX, we’re not number one but we’re right up there”-got groans instead of chuckles. “I experienced complete humiliation in those four-and-a-half minutes,” Oswalt recalled.

Anyway, he decided to start over, discarding his “meat-and-potatoes” shtick, pledging to be a better, more authentic comedic artist. “I watched. I wrote. I bombed. I bombed less. I wrote more. I started venturing out to other clubs the city had to offer.” Three years after, having paid some dues, Oswalt moved to Los Angeles, the site of much of what happens in Silver Screen Fiend. And where the title of the book kicks in. During the LA day, Oswalt toiled first for a legal firm, then as a disgruntled, ungrateful writer for MADtv. He was, he said, a superior-acting pain in the rear whose scripts were rife with typos. Nights, he divided his time between his real passions. He scrambled for stand-up gigs at comedy clubs and became, for the first time ever in his life, a manic film freak.

Oswalt saw every new mainstream movie, good or bad. More essential, he soaked himself in double features of old weird films, most often at the renowned revival house, the New Beverly Cinema, at Beverly Boulevard west of La Brea. It all began when he “took a bent, warped-spring seat in the briny darkness” and settled in at the Beverly for a night of prime, acidic Billy Wilder. Sunset Boulevard and Ace in the Hole. Four hours of cynical greatness. Soon after in 1995, it was Jerry Lewis’s The Nutty Professor, Orson Welles’s Touch of Evil, and the ghoulish Bloodsucking Freaks.

Where did Oswalt learn what unusual movies to see? I couldn’t be more pleased to discover that he relied on brilliant tomes penned by my film historian brother, Danny Peary. Danny’s three-volume Cult Movies 1, 2, and 3 became part of Oswalt’s “pagan shrine of Five Movie Books,” along with The Film Noir Encyclopedia and Michael Weldon’s sublimely sub-basement Psychotronic Encyclopedia of Film.

As a novitiate, Oswalt swore allegiance to his Five Books, being obliged to watch as many films listed therein as he could locate. He starred the films he saw and put the date viewed next to them. Why seek out The Nutty Professor? “…it’s listed in both The Psychotronic Encylopedia and volume 1 of Cult Movies. So, I mean I have to see it. To, you know… check it off.” Oswald spread out to other LA theatres: the American Cinematheque, the Tales Café (16mm projection), the Four Star (Gone With the Wind in a pristine 35mm print). He ventured to Santa Monica for current arthouse fare at the Nuart, a Landmark theatre.

Oswalt’s movie-crazy existence culminated in Fall 1995 at a Hammer Film Festival at the DGA Theatre. The best of British horror, “a lot of the same people over and over again. Peter Cushing. Christopher Lee….Buxom women with creamy skin and tight, frightened mouths and impeccable diction.” Six films a day for two days, 10 a.m. to midnight. Somehow, the fabulous Horror of Dracula was left off the bill, but Oswald got by famously with such delights as Five Million Years to Earth and, one I’ve never seen, Frankenstein Must Be Destroyed. Oswalt could say, with filmic authority, that it’s “hands-down Hammer Films’ best Frankenstein movie.”

Wish I had been there.

Patton Oswalt — he’s written an amusing memoir about a shaky time in his life when he was single, unknown, and obsessed about becoming a comedy star.

Why did Oswalt submit himself, for a time, to drowning in movies? I never quite understood that. It had some connection with him wanting to direct cinema, and some very tenuous relationship to his comedy career. In Silver Screen Fiend, the author jumps arbitrarily between the various parts of his artistic life. So there are also chapters on him becoming a more formidable stand-up artist, an “alt.-comedy” performer with friends like Louis C.K., Bobcat Goldthwait, and Sarah Silverman. Much of his LA funnyman stuff happened at the Largo, a club which specialized in fringe, oddball acts. It doesn’t get much more surreal than when Oswalt organized there an unauthorized staged reading of the screenplay for Jerry Lewis’s unseen, ever-unreleased 1972 kitsch masterwork, The Day the Clown Cried. (The tasteless day in which bozo Jerry heroically led a group of Jewish kids into the ovens of Auschwitz. That’s the actual denouement of Lewis’s self-directed, vanity feature.)

The funniest chapter of Silver Screen Fiend deals with neither film going nor stand-up. It’s about Oswalt’s being cast in a forgettable 1996 submarine flick called Down Periscope. He played a nameless radio operator, who appeared in many scenes of the movie reclining in the background but who, alas, had only one line: “Radio message for you. It’s Admiral Graham.” It’s Oswalt’s contention than any actor with one line obsesses about it, or maybe that’s a rationalization for his obsession. “Would I say, very matter-of-factly and professionally, that there was, indeed, a call coming in, and then drip a little acid onto the words Admiral Graham?” Or should he voice it unaffected, like a real radio man? “That would be more Method, I thought. More Meisner.”

The day finally came around, and Oswalt opted to do it the second way: “Clipped, businesslike, unemotional. A submarine radioman doing his job.” Dave, the director never knew the conflicted, pained backstory. “Aaand moving on,” Dave said. ”Next setup.”

Gerald Peary is a professor at Suffolk University, Boston, curator of the Boston University Cinematheque, and the general editor of the “Conversations with Filmmakers” series from the University Press of Mississippi. A critic for the late Boston Phoenix, he is the author of 9 books on cinema, writer-director of the documentary For the Love of Movies: the Story of American Film Criticism, and a featured actor in the 2013 independent narrative Computer Chess