Fuse CD Review: Charles Lloyd’s Indelible “Manhattan Stories”

Despite their somewhat muffled sound, both discs are valuable documents, not least because we hear the under-recorded Gabor Szabo in duet with Charles Lloyd.

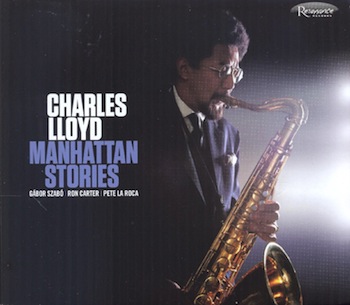

Manhattan Stories, Charles Lloyd (2 discs, Resonance HCD-2016)

Charles Lloyd: Arrows into Infinity, directed by Dorothy Darr and Jeffery Morse.

Charles Lloyd — circa 2014. Photo: Dorothy Darr/LDD.

By Michael Ullman

At one point in Arrows into Infinity, the expertly edited, beautifully filmed 2012 documentary about his life and career, Charles Lloyd is asked about the origin of his tone. He speculates that it must have come from the gentle, lyrical, understated tenor saxophonist Lester Young. It’s a sound that is powerfully seductive rather than imposing. One gentleman in the film describes the “life changing” effect of merely hearing the first phrase of Lloyd’s enduring hit, “Forest Flower.” Lloyd himself talks about improvising as shooting arrows into infinity. He points out that that isn’t as easy as it sounds: you first have to pull the bow back.

While leaving room for us to watch Lloyd roam the beaches of California, the film effectively touches on the musician’s entire career, which began in Memphis and includes a period when he played with blues legends such as Howling Wolf. Interviewed in the movie, Herbie Hancock, who played with Lloyd for a few weeks before Keith Jarrett became part of the group, notes that when he first arrived in New York, Lloyd didn’t play like a rough and tough New York musician: His sound was “like a flowing river.” It comes in “cascades of sound.” There is even “”an environmental aspect to it.” Lloyd explains his approach this way: he is a Pisces – he was born by a river and lives by the sea in Big Sur. His phrases come in waves. his pieces often end in long, sinuous codas. He’s not running changes; he’s leading us gently up and down a delightful path.

He grew up among musicians. In Memphis, the virtuoso pianist Phineas Newborn was his “Bach.” Lloyd remembers hearing the records of Charlie Parker when he was nine or ten: they were filled with “such grace and such elegance.” When he arrived in New York he looked up his childhood friend, trumpeter Booker Little, who taught him that jazz wasn’t about playing notes — it was “about character.” He took that advice to heart.

By 1965, when the two live performances captured on Manhattan Stories (released for the first time on these discs) were performed, Lloyd was already an experienced musician: his first recording had been made with Chico Hamilton in 1960. “I was in heaven” with Hamilton he recalls, and singles out bass player Albert Stinson as “a genius.” By the mid-’60s, Lloyd was a busy musician. He led his own group, often, as it is here, featuring guitarist Gabor Szabo, whom he met in the Chico Hamilton Quintet. He was also appearing with the ever-popular Cannonball Adderley. Unknowingly, he was on the verge of his greatest early successes, which came with the quartet that included Jarrett and recorded the blockbuster 1966 album Forest Flower.

The two sets found on Manhattan Stories were made with Szabo, Ron Carter, and drummer Pete La Roca. The venues are radically different: the first disc was a concert performance recorded in Judson Hall; the second was recorded in front of a raucous crowd at the club Slug’s, where we can hear loud conversations throughout the set. At Judson Hall, Lloyd brings his solo on “Lady Gabor” down to a whisper. That was impossible at Slug’s, where he begins the set with what was for him an exercise in extroverted blues, “Slug’s Blues.” Despite the somewhat muffled sound, both sets are valuable documents, not least because we hear the under-recorded Szabo in duet with the leader.

Famously, Lloyd would team up with a very young Keith Jarrett, bassist Ron McClure, and drummer Jack DeJohnette. This group was popular beyond what anyone might have predicted: it played before rock audiences, was invited to Russia, and was received ecstatically wherever it went. Then Lloyd withdrew. At the time he disappearance was a mystery, but Lloyd explains that by the early ’70s he was dabbling in drugs and had lost his way. According to Jack DeJohnette, Lloyd’s playing was suffering: he was out of tune. Lloyd went to the west coast, began his now life-long romance with his wife (and one of the film’s directors) Dorothy Darr and as he puts it, “tried to put a fence around the purity in his soul.” Gradually, he acquired a healthy life style and re-entered the music world. In his latest recording, and in the interviews that form much of the substance of Arrows into Infinity, he comes off as serene and re-dedicated. He’s playing as well as ever, riding what he calls “the high wire” of improvisation where “those wonderful blessings occur.” Those interested in Lloyd’s creative process should see Arrows into Infinity. His fans will eagerly snap up Manhattan Stories.

Michael Ullman studied classical clarinet and was educated at Harvard, the University of Chicago, and the U. of Michigan, from which he received a PhD in English. The author or co-author of two books on jazz, he has written on jazz and classical music for The Atlantic Monthly, The New Republic, High Fidelity, Stereophile, The Boston Phoenix, The Boston Globe and other venues. His articles on Dickens, Joyce, Kipling, and others have appeared in academic journals. For over 20 years, he has written a bi-monthly jazz column for Fanfare Magazine, for which he also reviews classical music. At Tufts University, he teaches mostly modernist writers in the English Department and jazz and blues history in the Music Department. He plays piano badly.