Book Review: “The fuzzy cinema of certain key events of my life” – Frankétienne’s “spiralist” novel “Ready to Burst”

Ready to Burst is a compelling, intricately structured story told in resourceful, oft-poetic language by a Haitian poet and novelist who has long been considered one of the Caribbean’s most invigorating authors.

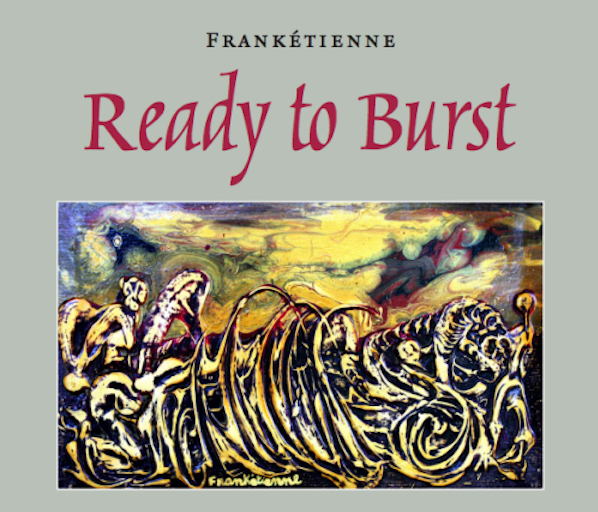

Ready to Burst by Frankétienne. Translated from the French by Kaiama L. Glover, Archipelago Books, 164 pp., $18.

By John Taylor

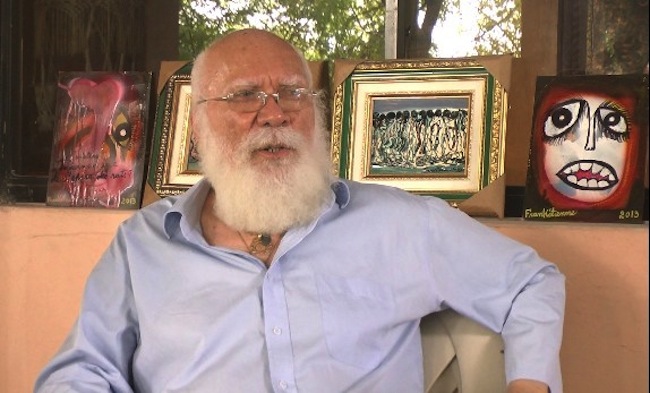

Hats off to Kaiama L. Glover, the translator, and to Archipelago Books for making Frankétienne’s unusual novel, Ready to Burst, available in English. The Haitian poet and novelist, born in 1936, has long been considered one of the most invigorating Caribbean authors—and he is a playwright, painter, and musician to boot. As far as I can count, based on various sources, he has published some fifty titles in French and at least ten in Haitian Créole. Significantly and logically (given the man’s overflowing creativity), many of these works have been initially self-published in Haiti so that Frankétienne could freely experiment with form and format. This specific novel dates back to 1968 (with subsequent re-editions and then a much-lauded new edition in France in 2013). By the way, the original title, Mûr à crever, has the additional strong (yet unfortunately not readily translatable) colloquial connotation of being ready or ripe to “die,” to “kick the bucket,” after hardships, a meaning that in fact becomes pertinent at the end of the story. Ready to Burst marks the first, long overdue, appearance in the United States of the energetic founder of literary “spiralism.”

Ready to Burst aptly opens the door to Frankétienne’s aesthetics and prolific oeuvre in that he defines “spiralism” on the very first page, in fact beginning with the very first sentence:

More effective at setting each twig aquiver in the passing of waves than a pebble dropped into a pool of water, Spiralism defines life at the level of relations (colors, odors, sounds, signs, words) and historical connections (positionings in space and time). Not in a closed circuit, but tracing the path of a spiral. So rich that each new curve, wider and higher than the one before, expands the arc of one’s vision.

This explanation continues all the way to the top of page 2 and is definitely worth perusing because of its humane and cosmic scope. But let me leap to the conclusion, which indicates the “Complete Genre” that awaits the reader of this book “in which novelistic description, poetic breath, theatrical effect, narratives, stories, autobiographical sketches, and fiction all coexist harmoniously.”

Although no simple linear plot can be ascribed to Ready to Burst, there is a main narrative thread of sorts: the ups and downs of Raynand, a mostly hapless character who falls in (and makes) love with Solange (the daughter of relatively wealthy parents), later becomes a clandestine passenger to Nassau in an attempt to find work, gets arrested and sent back to Haiti because he has no official papers, and more generally represents the impoverished, unemployed, young Haitians who eked out a living during the brutal dictatorship (1957-1971), especially beginning in 1964, of François “Papa Doc” Duvalier.

As the narrative proceeds, a particularly graphic passage evokes Nassau and especially Raynand’s forced return trip to Haiti, during which four similarly deported passengers commit suicide by jumping into shark-infested waters. The harrowing descriptions certainly apply to the peril and abject misery experienced by clandestine boat people in our day and age, nearly a half-century later.

Yet the vicissitudes of Raynand’s life form only one dimension of this novel. There is a political and historical backdrop, as I have mentioned. The author offers acute images of what it has been like to live in Haiti, going back to the day of Élie Lescot, who was the iron-fisted president of the country from 1941-1946, during the author’s own childhood, and moving forward from there to Papa Doc’s reign.

There is also Raynand’s friend Paulin, who is writing a novel which resembles, by his own admission, André Gide’s The Counterfeiters (1925), but which has the greater ambition of being a “vision of life,” a “spiral in motion [that] opens and closes in regular helices.” Paulin participates in the same plot as Raynand; they are friends, after all. At the same time, his role in the book opens out onto another level. He is not the main character, but, somehow, the meta-main character or even the omniscient narrator.

“I’m constructing my novel in a spiral,” he notably tells Raynand, thereby referring to the same spiralism practiced by Frankétienne, “with diverse situations traversed by the problematic of the human, and held in awkward positions. And the elastic turns of the spiral, embracing beings and things in its elliptical and circular fragments, defining the movement of life.”

In other words, is Paulin’s novel-in-progress one and the same with the Ready to Burst that we are holding in our hands? This is increasingly likely and, at the very end, the answer to this question is given.

Amidst such fictional passages, meta-fictional asides, and even a dialogue between Death and a Dying Man, autobiographical reminiscence also crops up. Italicized paragraphs exploring ideas, making various declarations, or relating dreams and memories yield to pages in the first-person singular. It is apparently the real author, Frankétienne, who is the subject matter of these passages because the dates and ages that are given line up with his own biography.

Or does some gap persist between the real author and the supposed real author as well? Be this as it may, Paulin at least expatiates on the novel that he is writing and points out that “these pages, despite their autobiographical nature, distinguish themselves from a private journal. They’re not burdened by any chronology. They’re more like a tangled film. The fuzzy cinema of certain key events of my life.” He adds:

The essential for me was to give free rein to my imagination as it rides memories that, paradoxically, belong at once to the past, the present, and even prolong my life into a formless future. Spiralist writing mixes up time and space. It’s an aesthetic approach that emerges both from relativity and quantic theory.

Frankétienne is, of course, not the first novelist to have been inspired by Einstein’s theory of relativity. Lawrence Durrell (in his Alexandria Quartet) comes to mind and especially William Faulkner, who used multiple narrative viewpoints as well. Without specifically referring to relativity, several early twentieth-century European novels attempted to create narrative structures according to scientific notions. If one stretches literary chronology even further, wouldn’t formally heterogeneous novels like Laurence Stern’s Tristam Shandy almost qualify as “spiralist”?

Frankétienne — he has long been considered one of the most invigorating Caribbean authors—and he is a playwright, painter, and musician to boot.

As to quantic (or quantum) theory, which is based on probability, the analogy with Ready to Burst—and nearly all literary works—strikes me as dubious. Practically speaking, the spiralism of Ready to Burst juxtaposes narrative levels and viewpoints that draw on, not the probability, but rather the logic of successive events. Not much, if anything, happens by random chance, which would be the closest conceivable analogy to the way, according to quantum theory, atomic particles and sub-particles behave stochastically. Raynand’s fate is inevitable. Moreover, Frankétienne’s powerful political point is that most Haitians, like Raynand (who nonetheless has a plucky side to him), are doomed to failure and despair because of the plight of the country.

Besides its storytelling aspects, Ready to Burst is therefore a kind of manifesto for spiralism. But I would suggest that the spiralist narrative “form” of the novel is less original than the spiralist philosophical “contents.” In this latter respect, Frankétienne’s provocative ideas, inserted rather often into the multilayered narrative, can be contrasted to similar ones developed in essays written by the poet and novelist Édouard Glissant (1928-2011) and the novelist Patrick Chamoiseau (b. 1953), both from the island of Martinique. In Kaiama L. Glover’s own elucidating article, “Spiralisme in the light of Antillanité“(Journal of Haitian Studies, Vol. 14, No. 1, 2008), Frankétienne is in fact reported as having declared: “I wrote the books Glissant should have written!” In any case, he has certainly been a catalyst for and a major actor in the literary and philosophical ferment that has taken place in the Caribbean over the past several decades. He has been a leading developer of a Caribbean world-view, with universalist scope, that has assimilated and moved beyond the concepts of “négritude” associated with the poet Aimé Césaire (1913-2008).

This being said, more memorable than Frankétienne’s rather frequent allusions to spiralism in this novel is his literary staging of Raynand’s mishaps, of Paulin’s struggles to write his novel, and of himself as the autobiographer behind all the scenes who has also—this is implicitly clear—suffered. Paulin’s aforementioned “fuzzy cinema of certain key events of my life” thus consists of three at once intersecting and merging lives, and their single, compelling, intricately structured story is told in resourceful, oft-poetic language.

John Taylor’s new collection of essays, A Little Tour through European Poetry, is available from Transaction Publishers. He is also the author of the three-volume essay collection Paths to Contemporary French Literature. He has translated several French-language poets, most recently Philippe Jaccottet and José-Flore Tappy. In 2013, he received the Raiziss-de Palchi Translation Fellowship from the Academy of American Poets for his project to translate the Italian poet Lorenzo Calogero. He lives in France.

Tagged: Archipelago-Books, Caribbean, Frankétienne, french, Haitian novelist, Haitian poet, Kaiama L. Glover, Ready to Burst