Book Review: In “Europe in Sepia,” Croatian Writer Dubravka Ugrešić Bets a Few Chips on the Future

Translator David Williams has hit upon a judicious combination of snappy repartee and dark underbelly that communicates essayist Dubravka Ugrešić’s rapier wit and black despair in equal measure.

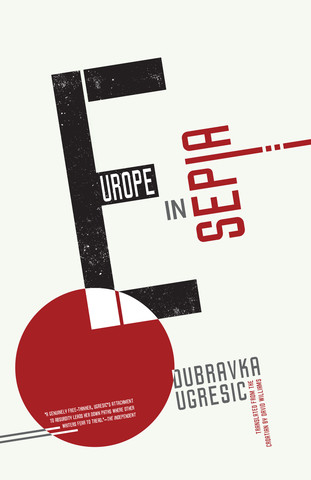

Europe in Sepia by Dubravka Ugrešić. Translated from the Croatian by David Williams. Open Letter Press, 230 pages, $13.95.

By Ellen Elias-Bursać

Dubravka Ugrešić has been writing novels and essays since the 1980s. Her newest book, Europe in Sepia, the sixth of her essay collections, follows on Have A Nice Day (1994), The Culture of Lies (1998), Thank You For Not Reading (2003), Nobody’s Home (2008), and Karaoke Culture (2011). Karaoke Culture was shortlisted for a National Book Critics Circle Award and Ugrešić has received a host of other awards for her nonfiction and fiction. Open Letter Press inaugurated their publishing venture with Nobody’s Home, and it has been the home for her last three essay collections.

As someone who has read most of Dubravka Ugrešić’s writing and translated some of it, I warmly recommend this newest volume. If you are familiar with her essays, which live right on the verge of story-telling, you will enjoy the latest twists and turns of her inimitable critical eye and the virtuosity of her translator, David Williams. Williams has hit upon a judicious combination of snappy repartee and dark underbelly that communicates Ugrešić’s rapier wit and black despair in equal measure. If you have never read one of her books, Europe in Sepia is a fine place to start.

Ugrešić has themes that recur, in variations, in much of her writing, and part of the sport of Ugrešić-watching is seeing how these themes modulate and develop over time. In this collection, with its stated framework of old sepia photographs, she suggests that we look back – with a critical eye – at a more revolutionary, more responsible Europe because it might give us the tools we need to look forward to the future. Ever since Thank You for Not Reading she has been taking the pulse of the rapidly changing state of publishing as well as the emergence of world literature. Regarding the latter, she has closely followed the transitions that have happened — and her role within them as a cultural figure — since 1989, now a full twenty-five years ago, when the East and West blocs dissolved.

In the title essay she describes her literary community; she takes us to a hotel room in Bratislava, Slovakia, its window facing, symbolically, inward toward the reception desk rather than out into the outside world. She is spending a few days at a meeting of her “tribe”: cultural managers, small-time NGO bosses, editors of obscure magazines, university lecturers, students and volunteers giving each other a passing sniff, wagging their tails, barking a little and then withdrawing… until the next time.

Ugrešić deftly sketches the world she traverses. In “Wittgenstein’s Steps” she describes a visit to the Dublin Botanical Gardens and perches on a set of steps: “The thought occurred to me that Wittgenstein might well have been sitting on these steps at the very moment my mother gave birth to me.” She is suddenly gripped by terror at her own lack of hope for the future. Then Wittgenstein’s words, “a man will be imprisoned in a room with a door that’s unlocked and opens inwards, as long as it does not occur to him to pull rather than push,” pull her away from panic and her thoughts are free to race off across the expanses of the world.

In each of these essay-stories, Ugrešić is resolutely in the world. But she is also in the clutches of a fear fed by a pervasive sense of vulnerability. “Mice Shadows” describes the flashes of panic brought on by unpredictable triggers: a sudden loud noise, a delayed flight, or the thoughtlessness of a young woman assigned to accompany Ugrešić when she is invited, without recompense, to take part in a literary festival. Despite Ugrešić’s chronic lack of cash, she treats her young minder to lunch: “And it was then I noticed a detail that shook me to the core. It was hard not to notice, because the girl didn’t make any real effort to conceal it. Her nimble fingers spirited the bill from the saucer and discretely slipped it in her handbag, all the while staring blankly at me through the quaint verticals of her eyelashes… . It was a mouse’s theft.” Presuming that Ugrešić was more privileged than she, the young woman assumed it was her right to submit the bill to her boss and be compensated for the cost of a lunch that the author had paid for.

Just as she organized Nobody’s Home around Ilf and Petrov’s The Golden Calf, Ugrešić structures her narrative here around Envy by Yuri Olesha. Her analysis of the novel echoes her anxiety about being unable to see into the future. Like the novel’s protagonist, Kavalerov, she perceives us as eaten by envy: “We are at the end of an era, unable to decipher the signs of what is coming. Our ability to imagine a new society has expired, and so we stand, like a blind man awaiting expectantly for an explosion…”

The piece “The Croatian Fairy,” which is about General Ante Gotovina, who was first sentenced to 24 years in prison as a war criminal by the War Crimes Tribunal in The Hague and then acquitted on appeal, opens with the description of a young woman who was savagely raped during the enthusiastic celebrations triggered by Gotovina’s release. Several other tales in the book reference the reality of life these days in Croatia; they analyze a special brand of Croatian cultural claustrophobia in ways that are strongly evocative of many passages in the writing of August Šenoa, Antun Gustav Matoš and Miroslav Krleža, all of them, like Ugrešić, major Croatian writers.

Dubravka Ugresic — part of the sport of Ugrešić-watching is seeing how her customary themes modulate and develop over time.

Her reading of the London riots is another facet of Ugrešić’s attempt to look forward: “And today, looking at its ‘feral’ children, society, stupefied by the mantras of democracy and free choice, continues to try and convince these kids that they’re cutting off the branch on which they’re sitting. They might be barely literate, but the children know that the branch has been rotten for years, and can’t hold their weight in any case. The only weapon they possess is their rage.” In a twist, Ugrešić confesses that although she should be on the opposite side, she is closer to those kids than she would ever have imagined: “If nothing else, the kids and I are bound — by fear.”

The essays I found the most compelling are in “Endangered Species,” the third and last section of the book. “A Woman’s Canon?” and “What Is An Author Made Of?” map the upsurge in women writers and the lack of a corresponding rise in the number of female laureates receiving major literary awards: “Female role models in the cultural field are rarely emancipatory, they just pretend to be.” She compares her gender assumptions to those of the younger generation: she grew up assuming that men and women are equals, but she senses that the younger generation of women have “grown up in the conviction that men and women have different roles, and that they need to work this to their advantage.” I find these pieces particularly interesting because Ugrešić has only been developing the theme of women in world and national literatures in her more recent writing. In her earlier writing she assiduously avoided focusing on the position of women in culture; she intensely disliked gender tokenism, which she perceived to be similar to the stubborn essentialism rife in Balkan nationalisms.

Yet her novel Baba Yaga Laid an Egg (translated in 2009) ends with a paean to abused women, and there is a powerful essay in Karaoke Culture on her own experience of being anathematized with four other women writers in Croatia during and after the war. Even she identifies this concern as a recent addition to the portfolio of topics she attends to: “I admit that of late I’ve developed an unpleasant involuntary neurosis: Everything I set eyes on, everything I touch, I immediately put through my internal calculator, working out the ratio of men to women.”

In the closing lines of Europe in Sepia, after sketching the forbidding direction that she sees the universe taking, Ugrešić offers us her personal vision for why it is that she feels compelled to continue writing, particularly amidst the cataclysmic vortex of a vanishing literary culture: “And this all gets me thinking – if I’ve already bet my lot in life on literary values and lost – maybe I should bet my few remaining chips on their future. Because who knows, perhaps tomorrow, to my every flight of fancy, a translucent book, letters shimmering like plankton, will appear in the air before me; a liquid book into which I’ll dive as if into a welcoming sea, surfacing with texts translucent and alive like a shoal of sardines. Perhaps tomorrow books will appear whose letters will converge in the air like swarms of gnats, with every stroke of my finger a coherent cluster of words forming… It’s not so bad, I think, and imagine how in the very heart of defeat a new text is being born.”

The beauty of this image is Ugrešić’s gift to us as, with her, we despair about what lies ahead.

Ellen Elias-Bursać has been translating novels, stories, and nonfiction by Bosnian, Croatian, and Serbian writers for the last twenty years. She has translated three books of David Albahari’s writing: Words Are Something Else, 1996, awarded the AATSEEL Award in 1998, for best translation from a Slavic or East European language; Gotz and Meyer, 2004 (Britain) and 2005 (US), awarded the National Translation Award by the American Literary Translation Association in 2006; and Snow Man (Canada) in 2005. She has also translated writing by Antun Šoljan, Dubravka Ugrešić, and Slobodan Selenić. She has co-authored a textbook for the study of Bosnian, Croatian, and Serbian with Ronelle Alexander, and has written a study on poet Tin Ujević and his work as a literary translator.

Tagged: Dubravka-Ugresic, Europe in Sepia, nonfiction-in-translation