Visual Arts Review: Ian Hamilton Finlay — Revolution Without a Manifesto

His art’s sunny, unhurried elegance, so at odds with its message, suggests that Finlay is taking a Swiftian rhetorical stance, along the lines of “if we can’t raise our children better than this we might as well eat them.”

Ian Hamilton Finlay: Arcadian Revolutionary and Avant-Gardener at the deCordova Sculpture Park and Museum, Lincoln, MA, through October 13

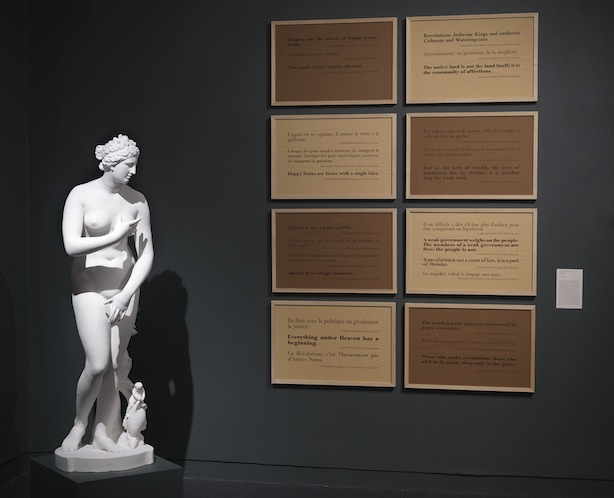

Installation view, “Ian Hamilton Finlay: Arcadian Revolutionary and Avant-Gardener,” deCordova Sculpture Park and Museum. Photo: by Clements Photography and Design, Boston.

By Peter Walsh

Ian Hamilton Finlay’s four-acre croft in the Pentland Hills, outside Edinburgh, contains what is probably the most famous British garden of the twentieth century. Landscape historian Timothy Mowl describes it as a “modern intellectual garden” and speaks of it in the same breath as vastly larger country house landscapes designed by John Vanbrugh, Charles Bridgeman, William Kent, and Capability Brown. It is a place, Mowl says, created to illustrate Finlay’s moral and philosophical views, with “war, art, and antiquity” prominent among its many themes. It contains over 200 artworks, many featuring written inscriptions.

Finlay, for want of a better label, is usually described as a poet. He might also be tagged the last member of the Scottish Enlightenment or a classic British artist-eccentric, along the lines of William Blake. All three sides feature in the large and ambitious exhibition this summer at the deCordova, whose own gardens along Sandy Pond in Lincoln make for an appropriate setting for Finlay’s work.

Born in Nassau in 1925, Finlay grew up in Scotland at a time when the London Times still quoted classical authors in the original Latin and Greek, without translations. By the time he was drafted into World War II, in 1942, the moral assumptions of this world had already mostly vanished. The war blasted what was left to smithereens. But the scrubbed-down, sun-washed, white marble classicism of the late 18th-century (not the garish paint, vulgar tastes, gory rituals, and messy pagan superstitions of the real Greeks and Romans) provoked Finlay’s life and work and words until the end.

With creative exaggeration, Finlay renamed his garden “Little Sparta” to invoke the uncompromising military stance of the Spartans. At the time, in the 1980s, his long-running conflicts with local tax officials recalled, in his mind, the Spartan Wars of the 6th century B.C..

FAITH, DEATH, JUSTICE, VENGEANCE, VIRTUE he writes, again and again, as if trying to resurrect a vanished moral Arcadia that never really existed. Finlay connects his own battle-ready neoclassicism, which he sets against the conspicuous failures of modernism, with that of the French Revolution. “REVOLUTION, n.,” he proclaims in a 1986 lithograph, made with Gary Hincks, “a scheme for the improving of a country; a scheme for realizing the capabilities of a country. A return. A restoration. A renewal.”

Ian Hamilton Finlay — In this work he makes makes endless sly and intertwined references to history, modern art, classical literature, war, art history, philosophy, contemporary events, and gardens.

The deCordova exhibition is mostly an indoor gallery show, with a few pieces, including non-working copies of Finlay’s elegant bee hives, titled Honey Was The Best Gasoline of Antiquity and The Honey, n. The First Sweetness, set in the sculpture garden outside. The show emphasizes Finlay’s origins in poetry and graphics, including postcards, broadsides, literary magazines, and small press work. It starts with poetry, slides into broadsides and poem-cards, his periodical, Poor Old Tired Horse (P.O.T.H.), the Wild Hawthorn Press, founded in 1961 with Jessie McGuffie, and concrete poetry, It ends in art work that features images, words, and phrases in classical forms.

As a visual artist, Finlay executed his ideas through craftsmen collaborators, with whom he shared credit. Technically, the results are superb: clean, elegant, and serene. But clearly the guiding genius is always Finlay.

Both the words and images are provocative, unsettling, and often darkly humorous, mixing modern weapons with classical and neoclassical allusions. Findlay is partial to epigrams from French revolutionaries, especially Louis Antoine de Saint-Just. The youngest of the major leaders of the Revolution, Saint-Just’s high-profile role during the Reign of Terror earned him the name “Angel of Death.” He was guillotined himself in 1794, at the age of twenty-six.

TERROR IS THE PIETY OF THE REVOLUTION is one Saint-Just epigram Finlay uses in these works. THE WARS OF LIBERTY MUST BE CONDUCTED WITH RAGE is another.

The violent imagery of revolution spills over and over in these works. In several, an abstracted image of a guillotine blade serves as the central motif. Finlay writes Marshall McLuhan’s catch phrase THE MEDIUM IS THE MESSAGE over one of them. In Apollo/Saint-Just after Bernini (1985-2003), Saint-Just appears in four bronze figurines in the guise of the Greek god of light, truth, prophecy, music, and poetry. Instead of the traditional Greek lyre, the revolutionary holds, in each image, a hand grenade, rifle, or machine gun.

Though the content sounds grim, the exhibition is anything but. The works on the walls and in cases are full of Finlay’s balanced, pleasing designs and sardonic humor. In the inscriptions in some: “Don’t cast your Revolution before swine,” “Don’t put all your heads in one basket,” Finlay seems to poke fun at his own obsessions. In others, he lays, next to genuine Saint-Just epigrams, “Liberty is not a legal quibble,” counterfeits of his own composition: “Justice is a cottage industry,” “Too much chatter sprains the soul.” In After Magritte, a 1991 lithograph made with Gary Hincks, Finlay replaces Magritte’s painted pipe with a machine gun over the famous Magritte inscription “ceci n’est pas une pipe” (this is not a pipe),

Installation view, “Ian Hamilton Finlay: Arcadian Revolutionary and Avant-Gardener,” deCordova Sculpture Park and Museum. Photograph by Clements Photography and Design, Boston.

Finlay makes endless sly and intertwined references to history, modern art, classical literature, war, art history, philosophy, contemporary events, and gardens. A post-card bears a Herbert Read quotation “In the back of every dying civilization sticks a bloody Doric Column.” In Les Femme de la Revolution after Anselm Kiefer (1992), Finlay depicts legendary women of the French Revolution — Madame de Staël, Marie Antoinette, Charlotte Corday — as botanical specimens.

All of this leaves you to wonder how much of Finlay’s violent text you should really take seriously. Neither the artist nor the show’s curator ever answers that question. The art’s sunny, unhurried elegance, so at odds with its message, suggests that Finlay is taking a Swiftian rhetorical stance, along the lines of “if we can’t raise our children better than this we might as well eat them.” Finlay, then, strikes a pose but the work is just edgy enough to keep him from being a poseur.

The deCordova installation ambles comfortably through the museum’s eccentric spaces, ending near the roof terrace. One might have asked for further details about Little Sparta (more is on the Little Sparta Trust website) but otherwise the hanging and the interpretive labels seem just right, striking a good balance between leaving the viewer in the dark and explaining too much. Curator Jennifer R. Gross’s catalogue essay makes useful connections to Finlay’s near contemporary and fellow provocateur, German artist Joseph Beuys, and the American “word artists” Ed Ruscha, Kay Rosen, Lawrence Weiner, and Jenny Holzer.

Gross concludes that Finlay’s revolution has no manifesto: “His call to reorder society is without definition, without solution.” Thanks to her thoughtful, well-organized exhibition, we are left to figure those out for ourselves.

Peter Walsh has worked for the Harvard Art Museums, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Wellesley College, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Dartmouth College, and the Boston Athenaeum, among other institutions. His reviews and articles on the visual arts have appeared in numerous publications and he has lectured widely in the United States and Europe. He has an international reputation as a scholar of museum studies and the history and theory of media.

Tagged: DeCordova Sculpture Park and Museum, Ian Hamilton Finlay