Fuse Book Review: A Volume That Explains Why Movie Moments Are Memorable

At times, David Thomson’s movie criticism resembles the approach of old-school British critics (the Walter Pater or John Ruskin variety) who didn’t mind occasionally cutting loose from being erudite to waxing lyrical.

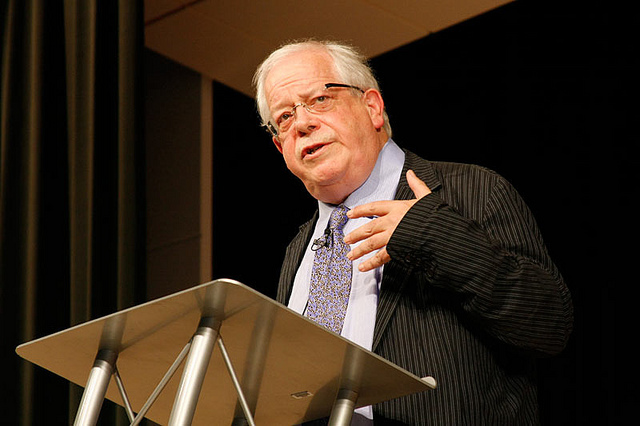

Moments That Made the Movies, by David Thomson. Thames & Hudson, 304 pages, $39.95.

By Matt Hanson

As coffee-table books go, David Thomson’s definitely got the competitive edge. Reading Thomson’s Moments That Made the Moves, his latest anthology, is kind of like being taken on a tour of portraiture curated by a world-class collector. I imagined that the book would be a kind of narrated slide show. The image came to mind not only because of the big-screen dimensions of the book itself, but because of Thomson’s prose style. At times, his movie criticism resembles the approach of old-school British critics (the Walter Pater or John Ruskin variety) who didn’t mind occasionally cutting loose from being erudite to waxing lyrical.

And that is a good thing. Thomson knows his films, all right, but the thing I love most about his writing is that it doesn’t end with heavyweight analysis. When he talks about a particular movie moment, film history, biography and contextualism is brought in, but he can’t resist becoming poetic about the scenes he’s writing about when he’s suitably inspired. Thomson once wrote a novella-length study of Nicole Kidman, which NYTimes critic Michiko Kakutani condescendingly referred to as a “mash note.” Since when was that so bad?

Thomson’s little gallery contains quite a few of the usual suspects. We get his take on venerable selections such as M, The Godfather, Citizen Kane, Psycho, Gone With the Wind, Bonnie and Clyde, etc, which is as it should be. As far as I’m concerned, classic films are old-hat only to cineastes, not to the general public. A surprising number of people I know who love movies have yet to see, or vaguely remember, a number of films that historians of the medium take for granted as popular classics. It might sound boring to take another look at the AFI movie canon, but Thomson keeps it fresh.

For example, the scene he picks from Kane (a personal obsession of his) isn’t the snow globe and it is only indirectly about the famous Rosebud. Instead, it’s the crucial but easily overlooked early scene when his staid, stern mother practically sells him to the bank while we glimpse (through the frame of the window) little Charles pulling his sled through the snow.

Sticking with Welles for a second, Thomson’s choice moment in The Third Man isn’t the charmingly nihilistic monologue Welles gives on the Ferris wheel. Instead, it’s the Van Gogh-influenced ending scene where the gal both men love – one deceased and the other in despair – slowly walks out of the tree-lined frame, gazing steadily into the horizon. Here‘s Thomson‘s take:

In the old days, this last shot acquired another providential quality. Coming at the end of a reel, the shot suffered in old prints – there were specks of dirt, scratches and blemishes. Traditionally, we expect “perfect” prints, every shot and frame, but this moderate and unavoidable acne of the conclusion…gave it extra pathos – it was as if the material itself were weeping or aging. There’s a lesson here: the “correct” image in a movie is one thing, but film is artifice, artificial and an art-work, and there is no reason why extra eloquence may not come with degradation.

For Gone With the Wind, it’s interesting to note that while Hattie MacDaniel won the Oscar for Best Supporting Actress in 1940 she was only begrudgingly allowed to attend the ceremony and wasn’t even permitted to sit at the same table as the rest of the cast. For Psycho, it’s the conversation between Norman and Marion Crane during the rainy night just after she arrives at the motel. Thomson rightly points out how eerily tender the scene is; an intimate conversation between two lost souls serving as a prelude to the murder to come.

Thomson also includes some wild card choices for scene material. We’ve got One False Move, Hoffa (!?), Burn After Reading, Zodiac, and Birth, the scene in question in the latter featuring (of course) a close-up of Kidman’s face. There is also Gwenyth Paltrow’s spontaneously overwhelmed lounge singer in Infamous, an opening scene that works precisely because it doesn’t explain itself. He also does quite a bit with Meg Ryan – there’s her gloomy, murky In The Cut and her infamously faked orgasm in When Harry Met Sally. As for Ryan’s faking the big O in a New York deli, I’m not totally buying Thomson’s claim for the “pathos of Meg Ryan,” but he is interesting when he separates the scene from the film: “your gaze turns to how the trick is done and why. That’s when you confront the inner wall that is a fear of sex or a feeling that that territory can never be entered.” It’s a little grand to phrase it like this, but it did get me thinking about the episode in a different way.

Part of the pleasure of the book is that it provides discoveries. Reading Thomson on Pandora’s Box, when the lubricious Lulu seduces her wealthy patron if for no other reason than the kick of it (spitting at his wife in the bargain doesn‘t hurt, either) got me to sit down and finally watch the entire film. I was glad to report it was as good as I‘d always hoped it would be. Same goes for Night of the Hunter, which is actually twice as good as you think it is the first time you watch it. The dinner scene at the end of Chinatown chilled me to the bone the first time I watched it, and John Huston’s oleaginous water baron is still about as evil a character as I’ve ever seen on screen.

I get the most out of Thomson’s criticism when he revisits movies I love but hadn’t seen in awhile. I never thought of Taxi Driver as being particularly meta, but after Thomson opines that it’s actually “a meditation on movie violence” I thought of it differently. Especially after reading Thomson on the Scorsese cameo backseat monologue which was one of those what-the-hell-was-that-moments, at least for me.

I never noticed the producer-like way Warren Beatty tells Faye Dunaway to fix her hair in Bonnie and Clyde. Her Bonnie peers into the camera, ironically unaware of her close-up. It’s just another amazing moment in a film that crackles with them, like sparks off a firecracker. Thomson is good on the moment in Bringing Up Baby where Cary Grant’s hapless paleontologist accidentally rips the back of Katherine Hepburn’s dress. The critic calls it “a moment of glory” that makes the film more interestingly subversive and anarchic, especially for 1938.

Agoraphobic cinephile that I am, the fact that I’ve seen many of these moments in films already doesn’t take the shine off seeing them reproduced on paper. The full-page illustrations are sharp, luminous, and suitably cinematic, too. In a way, the pages of the book serve as auxiliary screens in and of themselves. In some cases the layout is a bit clunky, but in others you get to see the still of a single frame blown up into startling focus. It was not a problem whether or not I knew what came next in the film: seeing a moment brimming with drama in ‘stopped time’ is pretty much what we go to the movies for in the first place.

It’s one of the reasons why I’ve never minded spoilers, actually. Sometimes knowing the ending or a major plot point makes the unfolding storyline that much more compelling. The same goes for re-watching, too. Knowing what’s going to come next does not necessarily negate the pleasure of watching a film again or having it analyzed critically. In the right company that’s half the fun. After all, what’s a moment for, especially in the movies? Thomson writes about film in a way that keeps you seeing as much as reading, moment by moment.

Matt Hanson is a critic for the Arts Fuse living outside Boston. His writing has appeared in The Millions, 3QuarksDaily and Flak Magazine (RIP), where he was a staff writer. He blogs about movies and culture for LoveMoneyClothes. His poetry chapbook was published by Rhinologic Press.