Book Review: “A Place in the Country” — A Heady Tour of W.G. Sebald Country

It seems deeply appropriate that a superb book of essays by W.G. Sebald about his favorite writers should be his swan song.

A Place in the Country by W.G. Sebald. Translated from the German by Jo Catling. Random House, 208 pages, $26.

By Matt Hanson

Like much of W.G. Sebald’s better-known work, A Place in the Country was first published several decades ago in his native Germany. Translated editions of his masterpieces, Austerliz and The Rings of Saturn, and other volumes have slowly found an American readership, a number of them while the writer (who died in 2001) was teaching literature and translation in England. It’s only right that his books were migratory in and of themselves, since their author was peripatetic to the bone. You might even say that exile was his muse, were it not for the seemingly endless and often-forgotten texts that supplied so much of his literary material.

A Place in the Country, the last of his books to be published stateside, consists of essays written as a tribute to some of the writers and artists he valued most during his relatively short career. In the introduction Sebald refers to the books he kept with “unwavering affection” in his briefcase wherever he went. Reading A Place in the Country is like having a tour through Sebald’s portable library. It includes novelists and poets like Robert Walser, Jean-Jacques Roussaeu, the Swiss-born German writer Gottfried Keller, the Swabian German poet Eduard Morike, and the paintings of Jan Peter Tripp. Don’t be taken aback if most of these names are unfamiliar. Sometimes reading about books you’ve never heard of is more fun than reading them yourself, especially if you‘re in good hands.

Sebald was a masterful and passionate reader and some of best writing can be found in his distinctive, collage-like mix of texts of all kinds. He also pretty much invented a literary genre all his own – a dreamy mixture of travelogue, scholarly investigation, memoir, and secret history – so paying tribute to some of the artists who inspired him is bound to become a little heady. And a little dark, too: Slate’s Mark O’Connell cracked wise when he imagined Sebald being shown a Rorschach test. The author responds to each flashcard by saying “that‘s the abyss, yes, that one too – I’m afraid they all pretty much look like the abyss.” I laughed when I read this, and it’s sometimes true, but I think of it more as Sebald going as far into the process of reading as he can. And if you look at something long enough, as the saying goes, it starts to look back at you.

The striking thing about reading Sebald on any subject, though, is how generous he is with his voice and attention. He had a genius for conveying earnest self-effacement, which is as rare among writers as it is among anybody else. Refreshingly, he doesn’t really tell you what to think or even what he thinks about a painting or a landscape. He meditates on the topic at hand, usually through the medium of someone else’s work. Sebald’s writing is a process of comprehension, in other words, and by the end of one of his characteristic digressions the reader finds themselves a good distance from where they started. When you read Sebald, you don‘t remember his personality per se, you remember his voice – how he describes the things around him, the way he lyricises the ephemera of existence.

Describing an almanac created by Peter Huebel, he writes: “Nowhere do I find the idea of a world in perfect equilibrium more vividly expressed than in what Huebel writes about the cultivation of fruit trees, of the flowering of the wheat, of a bird’s nest, or of the different kinds of rain.” As far as I’m concerned, finding poetry in an almanac is pretty good, but I for one had no idea there were different kinds of rain. Maybe I’m dense, but for me it’s always pretty much been wet stuff that falls from the sky. But, after all, aren’t revelations like that more or less why you read in the first place?

Sebald’s the kind of writer who’s excited about what’s in the margins of a painting rather than the figures in the forefront. When he looks at the pictures of his friend Jan Peter Tripp, it’s the details that move him more than the grand façade: “A red glove, a burnt-out match, a pearl onion on a chopping board: these objects contain the whole of time within themselves, as it were redeemed forever by the painstaking, impassioned precision of the artist’s work.” At times, the reader senses Sebald’s customary aversion to self-disclosure easing off. When he notes how objects in Tripp’s paintings have “the quality of mementos: objects in which melancholy is crystallized,” the observation illuminates some of what animates Sebald’s own work, especially in the haunted narration of The Rings of Saturn and The Emigrants.

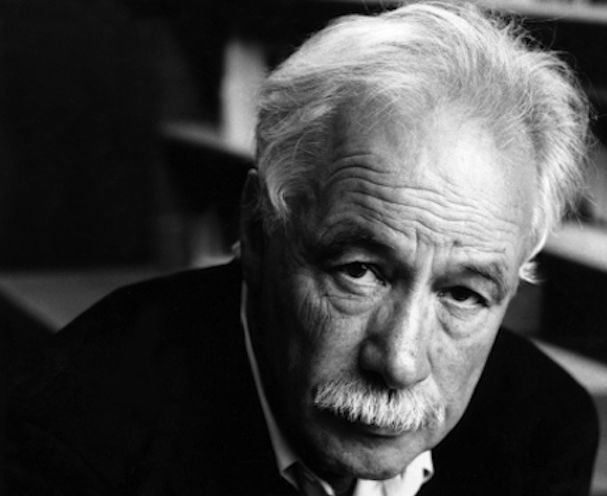

W.G. Sebald — If there’s anything that guarantees his enduring value as a writer, it’s surely his ability to imbue the lost or forgotten with an intuitive sympathy.

Sebald doesn’t write about the dynamism of great men or the anguish of star-crossed lovers. either. He is more comfortable with the anti-heroic, preferring modest failures and eccentricities to the grand sweep of history. You might expect an essay about Rousseau’s last days in Switzerland to be about his obsession with the social contract or a paean to the beauty of the noble savage. Instead, we follow the deeply misunderstood (and often manic) philosopher around on his promenades near Lake Geneva, taking solace in nature and solitude. The essay turns out to be a rather moving meditation on the limits of thought and the difficulty of finding peace within the life of the mind:

No one, in the era when the bourgeoisie was proclaiming, with enormous philosophical and literary effort, its entitlement to emancipation, recognized the pathological aspect of thought as acutely as Rousseau, who himself wished for nothing more than to be able to halt the wheels ceaselessly turning within his head.

It’s a similar story for Robert Walser, a writer who appears in Sebald’s prose narratives as a central point in Sebald’s literary cosmology. It’s partially to Sebald’s credit that Walser’s loose, unpretentious and subtly moving novels have started to find a North American audience in the past few years In his day, Walser was the kind of writer whom only other writers knew about. Kafka and Walter Benjamin deeply admired him and Herman Hesse once said that if Walser had a hundred thousand readers, the world would be a better place.

Walser’s microscripts, written in a near-illegible handwriting on scraps of paper he feverishly kept pulling out of his pockets, get a particularly careful treatment. This isn’t just because they are an example of how hard it is to write and what writing can eventually cost. Sebald explains that it “is also a work of fortifications and defenses, unique in the history of literature, by means of which the smallest and most innocent things might be saved from destruction in the ‘great times’ looming on the horizon.” This might sound a little grand or dramatic were it not for the fact that Walser was writing them while being institutionalized in the 1930s.

Sebald may as well be unintentionally describing himself when he (accurately) refers to Walser as “a clairvoyant of the small.” It’s a beautiful phrase that says so much about Walser that it crosses over into Sebald, too. Throughout the essays in A Place in the Country, we get an abiding sense of what such a thing could be and what it might have to say about Sebald’s work as a whole. If anything guarantees Sebald’s enduring status as a major writer, it’s surely his ability to imbue the lost or forgotten with an intuitive sympathy.

It’s this kind of sentiment that makes you regret the fact that there will not be more essays of his to come, due to the car accident that cut short his brilliant career. At the same time, though, it also seems deeply appropriate that a book of essays about his favorite writers should be his swan song. For a writer like Sebald, having anything but a posthumous reputation for appreciating the smallest of things would be less than his due and more than we could hope for.

Matt Hanson is a freelance writer living outside Boston. His poetry and criticism has previously appeared in The Millions and Knot From Concentrate, He was a staff writer at Flak Magazine until its untimely demise. Ekphrasis, his poetry chapbook, was published by Rhinologic Press.