Visual Arts Review: A “Street Talk” That Stresses Harmony Rather Confrontation

Chris Daze Ellis takes a serious risk. If you hang your work next to Berenice Abbott’s, it had better be as brilliantly framed, as firmly direct, and as perfectly focused as hers.

Street Talk: Chris Daze Ellis in Dialogue with the Collection, at the Addison Gallery of American Art, Phillips Academy, Andover, MA.

by Peter Walsh

A contemporary artist’s installation made up of items chosen from the permanent collection (“in dialogue”) has become a standard museum trope. Not infrequently, these exhibitions turn on a confrontation: the artist, speaking for an alienated or hoodwinked public, lambasts his or her host as a bastion of money and white male privilege. Alternatively, the visitor digs up a long-forgotten collection out of storage: an assemblage of Victorian ships’ clocks, say, or Chinese rhinoceros horn cups, and makes an installation out of that. Serving up a contrast to the customary calm of museum normality is the general rule.

In Street Talk at Phillips Academy’s Addison Gallery, Chris Daze Ellis, a visiting artist on the prep school campus, does none of this. Instead, he has pulled, from the Addison’s superb American collections, some fine 20th-century works and hangs his own paintings alongside them.

Ellis has some authentic credentials as a street artist and a rebel. In a nearby gallery, a Rigoberto Torres-John Ahearn painted plaster relief portrait shows him as the young “Daze,” his graffiti-artist street name. Spray can in hand, Daze lifts his handsome face in heroic defiance, as if confronting a freshly-scrubbed subway car. His Addison show, though, is all about harmony and continuity.

“I’ve chosen works…,” Ellis writes in the exhibition brochure, “that show not just comparisons, but a kind of art historical timeline of ways other artists have approached the urban scene in the past and what I am doing today. Some of those chosen works share themes with my own paintings.”

It is hard to fault Ellis’s selection. Mostly black-and-white photographs and small oils, these are early to mid-century classic images of New York and other gritty locations by Berenice Abbott, George Bellows, Walker Evans, Edward Hopper, Louis Lozowick, John Sloan, Alfred Stieglitz and other titans of American urban modernism.

Consciously or unconsciously, though, Ellis takes a serious risk. If you hang your work next to Berenice Abbott’s, it had better be as brilliantly framed, as firmly direct, and as perfectly focused as hers. And there’s the problem.

“I’ve always tried to find the perfect balance in my work,” Ellis writes, “between expression and representation, abstraction and realism.” Well, fine: except that the best art leans towards the thoroughly lopsided. No one praises Jackson Pollock, one of Ellis’s influences, for his “balance of abstraction and realism.”

Ellis’s canvases in this show are large, boldly painted, and often brightly colored. The works from the Addison are all smaller, tight, and tend towards the monochrome. The strongest Ellis piece in the show, Kiddyland Spirits, which hangs near the beginning, is the most stylistically restrained. Two figures with ambiguous expressions, whose lower extremities fade or fall off the canvas, are dwarfed by giant grinning bees in a carnival ride. The bright yellow and crisp black of the bees overwhelms the earthy tones of the rest of the painting. It is far from clear what is going on here (are these ghosts of rides past? faded memories? a murdered attendant?). But the painting states the unresolved mystery clearly and simply.

Elsewhere in this show, though, small, tight, and monochrome wins the wall every time.

In two small photographs from Bruce Davidson’s “Brooklyn Gang Series” of the 1950s, teenagers in bathing suits clamber over a Coney Island railing or, in one extraordinary image, swarm under the boardwalk like skinny white cats. The blank skies in the black-and-white prints suggest an overcast, steamy summer afternoon. Davidson’s ordinary beach scenes are foreboding, proffering hints of unfolding menace, volatile boredom, and simmering sexuality. At the same time, they are carefully plotted compositions of verticals and horizontals.

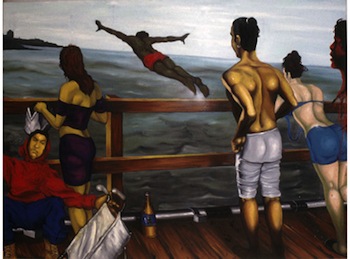

Hung between the two Davidson’s hangs Ellis’s The Coney Island Pier, made about four decades later. Four figures, seen from the back, watch as a fifth executes a graceful dive from the pier. The relaxed youngsters, neither children nor adults, lean or slouch; the composition leans lazily towards the water. “As a kid,” Ellis writes, “I would go to Coney Island during the summer months to take in the amusement rides and enjoy the sand.“ Painted in full color, The Coney Island Pier is a casual, sunny, nostalgic image, like a holiday cell phone pic posted on Facebook. A group of friends enjoy themselves beside the water, pleasant and winsome — but with none of the taut, gritty suspense of Davidson’s gang pictures.

Most of the Addison images focus on a few telling details or the vanishing effect of an instant. Louis Stettner’s Windshield, Saratoga Springs, 1957, silver print, catches a cloud burst just as it crashes across the glass, blurring and twisting the edges of the street scene outside. Leon Levinstein’s photograph Two Women, One in Hair Curlers, is all about those curlers. Edward Hopper’s Railroad Train of 1908 is just a single car and maybe a quarter of another, set high on an embankment: a composition of flatly painted, earth-colored diagonals. These artists know when and how to look and when to stop.

An eviscerated subway car lies In the center of Ellis’ Valley of the Kings/Fade to Black, looking as though Godzilla used it as a chew toy. It is a strong image and, by itself in a photograph or a small canvas like the Hopper nearby, could have been even more powerful. Instead, Ellis smothers it in expressionist drips and drabs of gray and white. An extraneous blob of black paint stretches across one upper corner. In another, a spray painter’s mask hangs over a painted image of one. As in several other canvases in this show, Ellis made his work but then kept going.

The edgy, working class New York of the 20th century is gone now and with it many of the scenes in this show. Several of the older artists used the dragon-like, long-demolished, and otherwise unlamented Third Avenue Elevated Railway as a key motif in their toughest urban landscapes. Ellis arrived on the scene just as the El and that old New York was swallowed up by the new one: a place, it seems now, increasingly of the Rich and the Homeless. The smoky skies, the noir alleys, the rusting industrial relics, the sweltering August asphalt, the unfocused restlessness and nameless yearnings of New York were being tidied up or away even as Ellis and his contemporaries painted them.

Like most of the other so-called “graffiti artists” of the 1980s, Ellis layers images and mixes eclectic and even contradictory sources: Warhol and Pollock, cartoons and Dada. In another exhibition at the Addison, his paintings hang to much greater effect. There, they seem a part of a whole. But maturing as an artist is more about leaving out and letting go than upping the ante or ducking the hard choices. These older artist generations teach that lesson very well.

Peter Walsh has worked for the Harvard Art Museums, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Wellesley College, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Dartmouth College, and the Boston Athenaeum, among other institutions. His reviews and articles on the visual arts have appeared in numerous publications and he has lectured widely in the United States and Europe. He has an international reputation as a scholar of museum studies and the history and theory of media.

Tagged: Addison Gallery of American Art, Chris Daze Ellis, Phillips Academy