Film Review: “Dallas Buyers Club” – Flipping the Coin of Masculinity

Dallas Buyers Club, though it does get decidedly sunnier once Ron is introduced to natural self-medication, which extends his life well beyond the projected thirty days, is not an open-and-shut case.

By Drew Boggemes

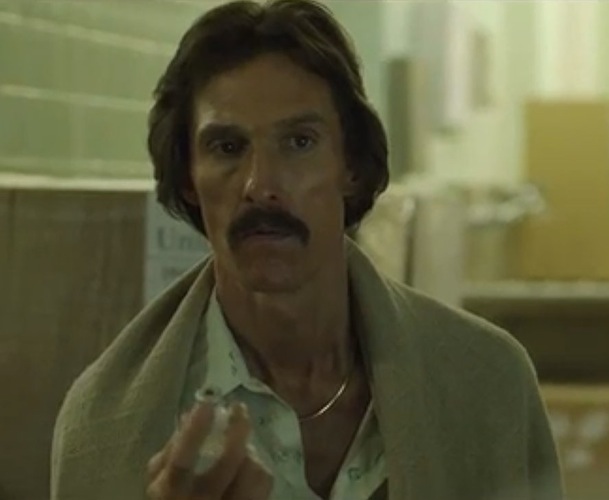

Since 2012, Matthew McConaughey has been doing some large-scale remodeling of his onscreen persona. He has taken an adventurous detour from a career largely made up of generic leading roles to portraying a rogues gallery of memorable characters, including the dictatorial owner of an all-male strip club, Jordan Belfort’s chest-beating mentor, and a near-mythic drifter living in a boat that sits in a tree. All of these roles channel the energy found in the best of McConaughey’s safer, more commercial work, diverting it into forays into riskier territory.

But his performance in Dallas Buyers Club is in a class all its own. Shedding nearly fifty pounds in order to play a scrawny and cowardly macho man, McConaughey drops his iconic image as if it was a suit of armor, creating a memorable portrait of a scraggy, vulnerable poser with delusions of being the Sexiest Man Alive. This is Ron Woodroof, a Dallas electrician and bull-rider who ends up a pioneer in the field of AIDS research.

Ron is the self-appointed dean of heterosexuality, and, naturally, an outspoken critic of its opposite. Much of his life consists of having sex with women, talking about having sex with women, or condemning homosexuals for not having sex with women. (He seems particularly outraged by the news that Rock Hudson caught AIDS via “smoking his friends.”) But director Jean-Marc Vallee, making use of bold visual and aural techniques, explores Ron’s sensory world, indicating the presence of a surprisingly complex and troubled inner life. At first, his mental disorientation would be chalked up to his unending drug use. But, once in the hospital after a mild electrocution on the job, he is informed that he has HIV, which will lead to AIDS, which will claim his life in the matter of a few weeks. Ironically, Ron seems more disturbed by the doctor’s insinuations about his sexuality than by the death sentence he has just received.

After wallowing in trailer-park hedonism for a bit, Ron accepts his illness and seeks help. Initially, he violently resists showing any empathy as the sole straight male in a world of ailing gays. But as the pain intensifies, his defenses – along with his immune system – begin to weaken. As does the film’s color palette, which changes from a glassy red hell to a beige and baby-blue purgatory. It feels as if the movie itself is morphing – suddenly the doctors, drag queens, and females acquire speaking roles. This is no longer a solipsistic cowboy joy ride.

However, Dallas Buyers Club, though it does get decidedly sunnier once Ron is introduced to natural self-medication, which extends his life well beyond the projected thirty days, is not an open-and-shut case. In fact, once the disease forces Ron to kick the booze and drugs and anonymous sex altogether, he only begins to reveal his softer side. He becomes close with a female doctor, develops a strained but dynamic friendship with a sassy transvestite, and eventually concocts a scheme to traffic the organic cocktail that made his bounce back to good health possible. This venture becomes the Dallas Buyers Club, a lucrative, if highly controversial and legally ambiguous, enterprise.

Ron, though considered a hero in gay culture to this day, never quite shakes his homophobic convictions in the film. He claws his way to the forefront of the AIDS survival rate, bringing most of Dallas’s queer scene with him, but he does so only in the interest of his own future, or perhaps because of the cash rewards. After he is given a good deal by an elderly gentleman couple from the Buyers Club, he respectfully shakes their hands. But when transgener friend Rayon hugs him out of genuine love, a familiar scowl returns to his face.

Dallas Buyers Club, from its jarring opening scene of animalistic sex in the dark, clearly has much to say on the subject of males. Men are compared to bulls and to women. There are men who dress like women. Ron’s development speaks volumes about what it is to be a man in today’s rapidly shifting cultural climate. He remains an outlaw, a descendant of the Duke, an unyielding rock in a violent stream. Yet he gets in touch with his softer side and learns to control his destructive impulses and bigotry. But never truly learns to tolerate the homosexual behavior he once so viciously decried.

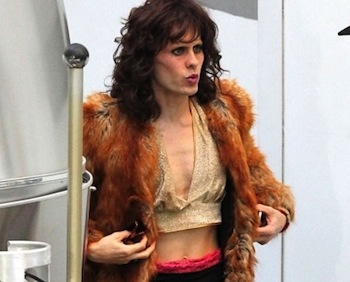

Ron’s rebuff of Rayon’s affection would simply be sad if not for Jared Leto’s equally deft performance. Donning heavy makeup, a turban, and a series of tight-fitting dresses that outline his bony physique, he, like McConaughey, radically reshapes his classic heartthrob image. His defensive energy rivals the star’s aggression, which is why Rayon comes off as consistent and brave enough to withstand Ron’s macho abuse. But this stoic mask turns out to be merely a powerful – and ultimately flimsy – show. In one harrowing scene, Rayon visits his straight-laced banker father dressed in suit and tie, without makeup or turban. Without his glamorous get-up, he is all jitters and flutters, as hapless as his judgmental father.

Ron’s story is undeniably a compelling one – not exactly a likable figure from the get-go, his transformation is the classic American triumph of the underdog. He beats the odds and emerges as a beloved rebel.

Drew Boggemes is a filmmaker and critic based in Detroit. He is the founder of the Detroit Underground Film Festival and currently maintains the blog Cinema: Dead or Alive.