Visual Arts Review: Picasso in Boxer Shorts — Red Grooms at Yale

Red Grooms specializes in high art cartooning with a nod to ideas about time, personality, and the formation of coteries that bear close investigation, or as curator Lisa Hodermarsky’s notes, invite visitors to belly up to the bar.

Red Grooms: Larger than Life at the Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, CT. Runs through March 9, 2014

By Debra Cash

Death’s never been jollier. Pablo Picasso, sandals on his feet and halo arcing around his bald pate, gestures thumbs up as he goes to heaven in American artist Red Grooms’ heroic 1973 canvas in Red Grooms: Larger Than Life at Yale. The show circling around Grooms’ mural-sized tributes to visual artists of the past is a hoot, shoehorning crowded genre scenes (think Brueghel or Bosch) into the region of knowing winks. In Grooms’ raucously colored illustrations, artists inhabit a world of their own references where their meaningful friendships can be as close as their contemporaries and as far away as their inspirational forebearers. This is high art cartooning with a nod to ideas about time, personality, and the formation of coteries that bear close investigation, or as curator Lisa Hodermarsky’s notes, invite visitors to belly up to the bar.

The three large works in the show, along with a series of incisive preparatory drawings, were donated by the late Yale alum Charles B. Benenson, a realtor and collector (particularly of African art) whose achievements included being a name on Richard Nixon’s enemies list.

The entry to the gallery has been draped in a canvas valance. The way in portrays New York traffic; on the way out, a paintbrush in the right hand of a red-bearded Van Gogh reaches beyond the doorframe. Everything in this show bursts its boundaries.

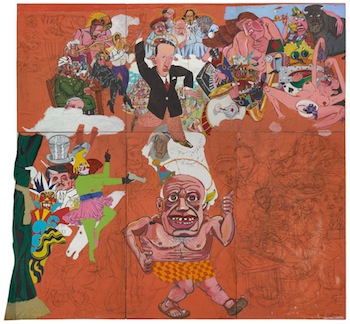

Van Gogh’s Arles paintbrush points towards Grooms’ 1973 Picasso Goes to Heaven, a 2-D circus tent of figures, some fully drawn, others sketched in charcoal and left unfinished. (Is that a banana stuck behind Pablo’s ear like pencil or is he just happy to see us?)

You can invent an Art History 101 quiz for yourself, or check out the wall legend: there’s Diaghilev with the Chinese Conjurer from the Ballets Russes’ Parade! Gertrude Stein en famille, with Alice B and her brother Leo! An elegantly dressed Igor Stravinsky, his checked pants rhyming with Picasso’s uninhibited checkerboard boxers! A watermelon balalaika! A lady model with a very strategically positioned bowl of grapes! And reviewing from a pillowy cloud in the celestial heights, Rembrandt, Titian, da Vinci, Velazquez and Michelangelo, massed like a cast of heavenly backup singers.

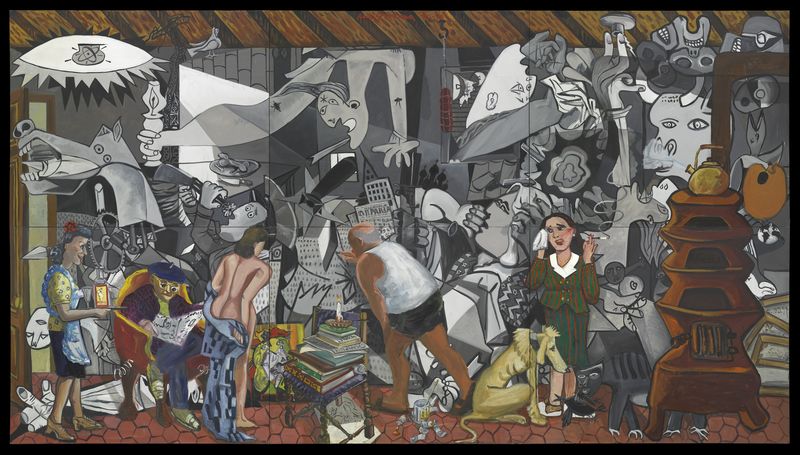

Red Grooms, “Studio at the rues des Grands-Augustins,” 1990-1996. Copyright: Red Grooms (ARS), New York.

Ole Pablo has his back to us — very much alive and hard at work on a slightly mashed up version of Guernica — in Studio at the rues des Grands-Augustins, painted by Red Grooms between 1990-96. Picasso working in his studio is a theme Grooms has delighted in for years: check out this smaller piece 2 p.m., Paris 1943 from the Marlborough Gallery. As he plays with the recursive dimensionality of a painting about painting a painting, Grooms’ workmanship is impeccable. Picasso’s heft throws a shadow on the Guernica canvas as he daubs at its surface while at his feet sits Kasbec, his hangdog Afghan hound and Dora Maar weeping and as flat as a Warner Brothers cartoon. Cubism, who needs cubism? The plump whistling teakettle may have a suggestion as it blows steam into a minotaur’s nostrils from atop a totem pole of a cubist red woodstove. Violence — maybe during the Spanish Civil War, maybe during the war in Bosnia which was underway when Grooms was painting the picture, or even during the drone attacks during America’s expeditions in Iraq and Afghanistan — is memorialized in the midst of the painter’s mundane working life, like the trussed salami hanging from a hook on a beam in the studio’s ceiling.

The final, and perhaps most ambitious of the three big Grooms pieces in Larger than Life is Cedar Bar from 1986. Cedar Bar is simultaneously heroic, with its array of New York School Abstract Expressionist celebrities and faux gilded frame, and antiheroic as the portraits present the artists’ personalities like a punch in the kisser. You can almost hear the hubbub as paint-splattered Willem de Kooning and Jackson Pollack are at fisticuffs on the barstools; catch Franz Kline in a blinding yellow suit kissing up to critic Harold Rosenberg; and contrast the different degrees of self-possession of Lee Krasner and an almost corporate-looking Helen Frankenthaler (and thanks, Red, for putting the women on an equal footing in your painting, even if the market didn’t do so when they were at the height of their powers). In an insider bonus, young Red and older Red mix drinks behind the bar, schmoozing with the customers. In Cedar Bar, Grooms is going for something reminiscent of the 17th century collective portraits of Dutch guild members: they’re good if you know who they are, even better with access to the back story of their relations among themselves.

Red Grooms: Larger than Life is a small show that packs a wallop, but its impact ripples beyond the one room where it is installed. Make the time to descend a few floors and stroll among Yale’s permanent collection of modern art where Grooms’ would-be models have left their traces in the great Picasso First Steps, a brace of Pollacks whose textures need to be experienced in person to convey their energy, and Frankenthaler’s yolk yellow Island Weather II. Red Grooms tell us a lot about these artists: the works are the reason it matters.

Debra Cash has reported, taught and lectured on dance, performing arts, design and cultural policy for print, broadcast and internet media. She regularly presents pre-concert talks, writes program notes and moderates events sponsored by World Music/CRASHarts and cultural venues throughout New England. A former Boston Globe and WBUR dance critic, she is a two-time winner of the Creative Arts Award for poetry from the Hadassah-Brandeis Institute and will return to the 2014 Bates Dance Festival as Scholar in Residence.

c 2013 Debra Cash