Visual Arts Commentary: In a Room with Rothko

The Arts Fuse is pleased to announce that “In a Room With Rothko,” by Anthony Wallace, posted last year, was awarded a Pushcart Prize Special Mention in the Pushcart Prize XXXVIII Best of the Small Presses (Norton & Co, 2013). Wallace’s short story collection The Old Priest was the 2013 winner of The Drue Heinz Literature Prize. The Fuse review of that volume here.

A personal meditation on the art of Mark Rothko, ranging from memories of a mystical encounter with his paintings to thoughts on the recent SpeakEasy Stage production of “Red,” which is based on the life of the artist.

By Anthony Wallace

Back in the Clinton-era 90s I made occasional trips to Washington, D.C., where a college friend of mine had recently moved because of a job transfer. I was living in Philadelphia at the time, and between jobs, and it was a fairly pleasant three-hour train ride from 30th Street Station in Philadelphia to Union Station in D. C. They had just done an extensive renovation of Union Station, with its turn-of-the-last-century grandeur, including hundred-foot ceilings and classically inspired sculptures and a triumphal arch—the triumph of the Machine Age?—and one arrived in the nation’s capital in something like grand style. On these trips I’d take only one small suitcase, and from the train station it was an easy walk to my friend’s apartment on Capitol Hill Northwest. We were college friends, from back in the 70s, and I was still unmarried, but he was going through his first divorce and not doing so well at it. In the evenings we’d go out to dinner and drink too much, the way college friends usually do when they haven’t seen each other in a decade, and one of them is getting a divorce, and they hate their jobs, or lack thereof. During the day, while he was at his job at the U. S. Treasury Department, I’d wander among the tourist attractions like the tourist I was.

Eventually I made my way into the National Gallery, the sharply, shockingly angular concrete and glass modern wing designed by I.M. Pei, a pterodactyl-sized Calder mobile hanging thirty feet above the lobby, and from there eventually to the Rothko Room in the basement. That was twenty years ago, and I don’t remember the titles of the paintings—not memorable titles, anyway—but I think there were four or five of them, medium to large, and they were all Rothkos from the major period, different planes and fields of color, what anybody would call large abstract paintings that seemed to concern themselves with color and form. If you wanted to sound like you knew something about art, that’s probably what you would say about them. This first visit was on a winter weekday morning, and nobody else was in the room, at the center of which was a long leather-upholstered bench. I sat down, not really to look at the paintings, at first, but to catch my breath, for I was still smoking cigarettes back then, and not watching my weight, and I also had a low-grade hangover. I can’t remember any of those visits to Washington without remembering the hangovers, beer-and-nicotine hangovers that made me feel a little out of kilter with the world, with my own sense of speech and movement, especially in a city I didn’t know very well and that was said to be dangerous. As I settled down and took off my coat, the paintings for just a moment seemed to move, or perhaps breathe is a better word. The room itself rippled a little.

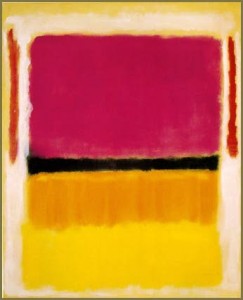

I ascribed this sensation to the hangover. There was one painting directly in front of me that looked at first like an abstract depiction of a Big Mac: three main blocks of color against a darker rosy-black background. Two larger, lighter, squarish blocks of color sat top and bottom, in the middle of which was a darker, thinner rectangle of blackish-brownish-gray—the overcooked hamburger. As I looked at the painting, the colors began to pulse and vibrate a little, each in their own way, perhaps magically, perhaps atomically. The darker, smaller bottom bun was a fleshy color with some purples and magentas running through it. It pulsed silently without moving out of place, not showing much conflict, the overall effect like a quiet drizzle. The skinny oblong middle section, the burger, sat quietly in its place, not struggling to escape the confines of the sandwich it was the center of, but sizzling in a way that was different from the movement of the block of color it was sitting upon, or floating just above. The larger, puffier section, the top bun, a pellucid nectarine scratched through with darker streaks of blacky rose and vermillion, moved in an airier way, and upward. It suggested ascension. As I began to see the movement and interplay of these three fields of color, it occurred to me that the darker, flatter, non-moving background was the void within which these three living things moved and breathed—palpitated.

Three different states of being standing in some relationship to one another, with the void as a constant. Different states of being that could drift like clouds, touch one another, veer off, stretch, break apart, regain their shapes, regain their positions within the larger harmony of the canvas, begin moving once again. The bottom square undulated with a feeling more of sea than of land, the shimmery depths of el mar. The middle section was earth, the smallest but most important piece for humans, and it made my beer-soaked body homesick, and a little hungry, just to look at it. The vibrant top field of color was sky, expanding upward, stretching, shape-shifting, with a sound like rising vapors mixed with the draw of a rosined bow across an open low cello string when I looked from that ascending mass to the small, blackened piece of earth that called me back to it, again and again, even as my eyes continued to strain upward. Sibilant wet hissing, like the sound of steam radiators in my friend’s ancient apartment building, mixed with the scraped sound of cello strings, plus a few deep, muted sounds of reeds, possibly, as I continued to stare, and again the vertiginous feeling of being pulled upward, and the larger square going white at the very top, impurities burning away in the experience that resolved finally to the silence and stillness of the center, which seemed suddenly to go black and still.

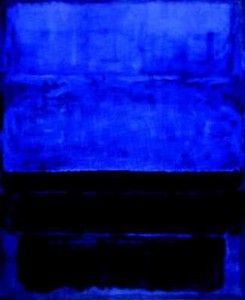

I stood up. My hangover had lifted. I walked closer to the painting I’ve described, almost as if to poke it in the chest and say, You didn’t really just do that, now did you? The paintings on the other walls looked on; we had not been alone. There was one, not quite as large, that was mostly black and gray, or grayscale, like a still, dead field in winter. There was another one, about the same size as the first, with rectangular blocks and planes of blue and green, rich winter blues and greens, Miles Davis blues and greens, Christmas tree blues and greens, the best pharmaceutical drugs you’ve ever taken blues and greens: rectangles that looked like the various streets and intersections one would see while standing on top of a building in a crowded city. At nightfall. In winter. With the creaking traffic and the crunching of tires on snow and the tinkling of tire chains and the horns of the taxicabs, reedlike, trailing from trumpets and saxophones to a single muted oboe. Rothko’s paintings can be looked at head on, they can be seen as landscapes or seascapes, for there is almost always a line that is like a vanishing point that separates land or sea from sky. They can also be looked at as vertical landscapes, as if we are looking down at these marvelous strips and grids of color and movement from the very top of a very tall building. In all of it seems to me to be the upward struggle, the movement toward ascension and purification. I sat down, looked once more at my first friend the cosmic Big Mac, pulled on my coat, checked my pockets for my hat and gloves, and left. Outside on the Washington Mall it was cold and bleak, sparsely populated, the homeless outnumbering the tourists, the world of appearances that I’d returned to. That I’d chosen to return to. A bowl of New England clam chowder and a bottle of Sam Adams at the cafe in Union Station was all I could think of.

Later that evening I told, or tried to tell, my friend about the experience. I had always been the more creative one, and I think my attitude toward art annoyed him a little, the high-handedness of it, though he always tried to keep up his end of the conversation. “Oh, I read about those pictures,” he said. “They say Rothko was painting prayer. What do you think that’s all about?” “Well,” I said, “I suppose it all depends what you mean by prayer to begin with.” “Asking God for help? Probably something I should try once in a while.” “No, I don’t think that’s what he means by prayer, if that’s the right word. I think it’s about a certain kind of experience, and one that does involve communication, though not the kind that involves words.”

I thought about it on the train ride back to Philadelphia, and I thought about it a lot throughout the Clinton-era 90s when I’d go two or three times a year to visit my college friend, and to visit the Rothko paintings, too. I developed a personal relationship with the paintings, or in a way I did. I think it’s more like I developed a personal relationship with Rothko himself, the way I had developed a personal relationship with Miles Davis and John Coltrane before that. The sense in both musicians, at their best, when it seems that they are speaking directly to us, and that they’ve invented an entirely new language in order to do so. Not just to speak, or just to speak whatever they might need to speak, but that they need to speak it to us, personally, as individuals. Each time I’d go into that room I’d enter into the conversation, or try to, and each time I also became more mindful that the paintings were speaking to one another—and doing so when no human being was in the room. I would become annoyed when from time to time they’d close me out of the conversation, when they’d become merely interesting shapes of colors, or, worse yet, when I could only see that first painting I had made friends with as a silly, pop-art Big Mac. Mark Rothko is not Andy Warhol, after all. The paintings had opened up to me so easily the first time, but it wasn’t always like that. Sometimes I think the hangovers helped. They opened me up, somehow, made me more fragile, more vulnerable, more depressed, too—more in need of what the paintings have to offer, and more in tune with it, too.

My adventures in Rothko-mysticism, if you’d like to call it that, culminated when the National Gallery mounted a sprawling Rothko retrospective in the summer of 1998. I was in a serious relationship by then, and I took my girlfriend to meet my college friend, and also to meet my new friend Rothko. We walked through room after room of Rothkos, tourists were swarming the halls, I was pontificating to my girlfriend, my college friend, also his current girlfriend, and I don’t think anybody got the experience I’d gotten that first day and a handful of times afterward. I felt stupid, and like I’d betrayed something important, and very private, even though my intentions seemed honorable enough. You phony, Rothko seemed to whisper to me as we walked from a roomful of late masterpieces into the museum cafeteria. You big fat artsy-fartsy phony.

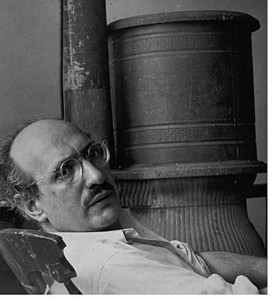

Mark Rothko in his studio Mark Rothko in his West 53rd Street studio, c. 1953, photograph by Henry Elkan, courtesy Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Rudi Blesh Papers

I didn’t hold that last bit of spite against Rothko. I’d deserved it, certainly. I’d broken Rothko-Omerta. Right after that I broke up with the serious girlfriend. I found a job teaching at Boston University, and I’ve not seen another living Rothko again. I do I think of Rothko the same way I think of Miles and Coltrane—close friends I’ve made along the way as I’ve clutched at my own blackened bit of ground and glanced occasionally upward at the inhospitable sky. Sometimes even purple prose doesn’t help, and I wish there was a Rothko room closeby, someplace safe I can duck into the way Clark Kent ducks into a phone booth. Now these many years later a play about Mark Rothko called Red has come to the Boston Center for the Arts. The play has gotten a lot of attention in various productions in major American cities, including in D. C. this past fall where the National Gallery exhibited three of the so-called Seagram Murals. Red was first performed in London at the end of 2009 and received a Tony Award for Best Play in 2010.

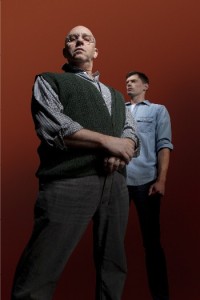

I attended the SpeakEasy Stage Company production of Red at the Wimberly Theatre on the evening of Thursday, February 2nd. With me was a fairly large group of Boston University students who were attending the play as one activity in a four-section writing seminar called “The Theater Now.” Red is a two-man play, the story of Rothko and a fictitious studio assistant during the time Rothko was painting the Seagram murals for a record-breaking commission that would be worth two million by today’s standards. Rothko eventually kept the paintings and returned the money. His paintings, he learned somewhere along the line—it’s a matter of some debate exactly when—had been intended as decorations in a Four Seasons restaurant, pretty pictures for bored, overfed rich people. The murals instead went in smaller groups to the National and the Phillips in Washington, the Tate in London, other important galleries across the globe. In the play Rothko is portrayed as arrogant, insecure, temperamental, abusive, grandiose—the familiar cliché of the artist who thinks he is above it all, the Modern Prometheus who gives us what we need most and who pays most dearly for it, at least in his own mind. He berates, humiliates, and even physically attacks with paint his young assistant Ken, but in the end we learn it was all an educational process, young Ken’s apprenticeship with an older Master. Rothko sends him in the final lines of the final scene back out into the world, instructing him to “create something new.” Ken goes. Rothko stays behind, staring at the painting he looks at when he looks directly at the audience.

Ken, I think we know, is sadder but wiser for his experience with Rothko that is ninety minutes of stage time and two years of actual time. Maybe he’ll paint “something new,” maybe the experience with Rothko has cured him of that ambition once and for all. Either way, he has learned something important about ART. What happens to Rothko by the end of this play is much less certain. The real Rothko committed suicide ten years later, and certainly that fact informs the play for many if not all audience members. In the final scene, just before Rothko picks up the phone to announce he’s sending back the check and keeping the paintings, Ken comes into the studio to find Rothko unconscious and covered with what looks like blood but that turns out to be red paint. He is dripping with it from the wrists and chest, and it is an image that conjures the suicide without staging it. At the end of the play Rothko is alive, alone, and staring into one of his paintings. He seems to be weeping. His face moves, distorts, rearranges itself like one of his paintings. Snow falls down in front of him, like a magical screen separating him from the audience, like the pulse and whirl and spark of atoms in the void. Then everything goes black. Black swallows red, perhaps, death swallows life, as the play would seem to imply in the painterly language it has created, and the audience is supposed to feel…

Reverential in the face of genius that has sacrificed everything for art? Aghast in the face of genius that has destroyed itself for art? Sad and puzzled in the face of the ineffable? Strangely connected to a man who could only seem to connect with others through his paintings? Uplifted by a triumph of artistic will and integrity? Brought to pity and terror by the tragic fall of an artist annihilated by his own art, which is to say his own ego, ambition—and, perhaps, delusion?

Rothko himself said that he was interested “only in expressing basic human emotions—tragedy, ecstasy, doom, and so on. And the fact that a lot of people break down and cry when confronted with my pictures shows that I can communicate those basic human emotions . . . The people who weep before my pictures are having the same religious experience I had when I painted them. And if you, as you say, are moved only by their color relationship, then you miss the point.”

Thomas Derrah (left) as Artist Mark Rothko and Karl Baker Olson (right) as his assistant in the SpeakEasy Stage Company production of RED.

The artist, however, has not had the last word about his art. There is some question among critics about what Mark Rothko was doing, and the extent to which he succeeded at doing it, and the same question seems to apply to Mr. Logan’s play and to his fictional treatment of a real-life person. What is he doing with his subject, and why is he doing it? Is he out to give an understanding of his subject that in its final penetration will outperform a documentary? Is he out to explore the painful contradictions of life and art as well as between artist and work of art: the dialogue between self and soul of an artist in the throes of creation and at the height of his power? All of these things, I suppose, which is to say that this two-character, ninety minute play is as ambitious as its subject. But why speak about things that demand silence as a response? Why speak about the man when the art he created is what’s of interest? Why use words to get at a subject who himself was looking to express something beyond the limitations of spoken and written language?

Red is funny, well written, ambitious, and it does shed some light on the grasping after immortality, or even mere importance, that has consumed many an artist. It also gives more than a glimpse of an artist in the process of making his art. We get a palpable sense of the creative process, and of the mixture or arrogance and self-doubt that would seem not just unavoidable but somehow necessary to the making of art intended to be “important.” At the same time, Red has given me an understanding of how a man might be dwarfed by the power and grandeur and mystery of his own art. This would seem to be the paradox that the play turns on, and it is a human paradox that is at the center of a human tragedy—what some fans and critics seem to assume as the tragedy of Mark Rothko’s life. But the work itself, I’d say, achieves something different: the tragedy that exists beyond the human sphere, the cosmic tragedy that humans sometimes participate in, and which is related to their own tragedy, but which is larger than it, and importantly separate from it.

I think this is the eternally, relentlessly enacted agon that Emily Dickinson captured in poem 1494:

The competitions of the sky

Corrodeless ply.

They did a play about Dickinson, too, come to think of it, for genius is always “interesting,” and geniuses themselves are easier to understand than the work they produce. In Red it seems that John Logan has sent a sticky red Valentine to a giant of twentieth century American art. In considering the play with respect to the art that informs it, it seems that my only recourse has been to send another.

Tagged: Honorable Mention, John Logan, Mark Rothko, Pushcart Prize, SpeakEasy Stage Company

This was an engaging, well-written article by someone who certainly should continue writing in this vein. His observations about Mark Rothko are interesting and on-point. Really enjoyed this so much. Kudos to Mr. Wallace.