Children’s Book Reviews: Exciting Innovators –Three Surprising Picture-Book Biographies

By Cyrisse Jaffee

Three lesser-known innovators are profiled in these intriguing picture book biographies.

Amazing Abe: How Abraham Cahan’s Newspaper Gave a Voice to Jewish Immigrants by Norman H. Finkelstein. Illustrated by Vesper Stamper. Holiday House, 2024.

I’m Gonna Paint! Ralph Fasanella, Artist of the People by Anne Broyles. Illustrated by Victoria Tentler-Krylov. Holliday House, 2023.

Comet Chaser: The True Cinderella Story of Caroline Herschel, the First Professional Woman Astronomer by Pamela S. Turner. Illustrated by Vivien Mildenberger. Chronicle Books. 2024.

Born in Vilna, Lithuania (then part of the Russian Empire) in 1860, Abraham Cahan was a public school teacher, an unusual choice for a Jewish boy in Czarist Russia. He had a talent for languages and spoke his native Yiddish as well as Russian. Pursued by the police because of his left-wing political activism, he became one of the millions of Jews who emigrated to America from Eastern Europe between 1880 and 1914. Like so many other immigrants, he was unfamiliar with many American customs. To help, he became one of the founders of Forverts (The Jewish Daily Forward, later The Forward), a Yiddish-language newspaper that offered advice, information, and guidance in a language understood by Jews from many different Eastern European countries. Cahan, who was editor-in-chief for over 40 years, offered folks a link to their homelands and also taught about American history, explained voting, urged readers to fight for better working conditions by joining unions, and published important Yiddish writers. A special column, A Bintel Brief (Bundle of Letters), allowed readers to write in with their questions and concerns.

Born in Vilna, Lithuania (then part of the Russian Empire) in 1860, Abraham Cahan was a public school teacher, an unusual choice for a Jewish boy in Czarist Russia. He had a talent for languages and spoke his native Yiddish as well as Russian. Pursued by the police because of his left-wing political activism, he became one of the millions of Jews who emigrated to America from Eastern Europe between 1880 and 1914. Like so many other immigrants, he was unfamiliar with many American customs. To help, he became one of the founders of Forverts (The Jewish Daily Forward, later The Forward), a Yiddish-language newspaper that offered advice, information, and guidance in a language understood by Jews from many different Eastern European countries. Cahan, who was editor-in-chief for over 40 years, offered folks a link to their homelands and also taught about American history, explained voting, urged readers to fight for better working conditions by joining unions, and published important Yiddish writers. A special column, A Bintel Brief (Bundle of Letters), allowed readers to write in with their questions and concerns.

Although the narrative is well-written, one wishes to know more about Cahan as a person. Some details are left unexplained. For example, we’re told that Jews were only permitted to live in what was called the “Pale of Settlement” but not why those restrictions existed. Similarly, the author states that life there “revolved around the Jewish calendar” but not what that meant. And the illustrations, while appealing, give the impression that the immigrants were clean, well-fed, and mostly cheery. (A scene showing a little girl seemingly playing with a mouse or rat under the dining room table is especially misleading.) Even the streets of the Lower East Side look prosperous. There is a curious lack of grittiness, even though it’s alluded to in the dilemmas that the Forverts readers wrote about. Nevertheless, this is an interesting look at a much-loved Jewish institution of the early 20th century and the man who helped make it so.

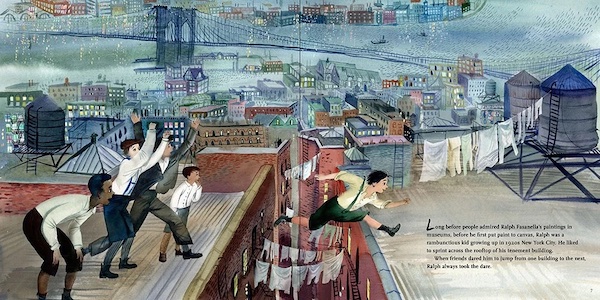

Perhaps Ralph Fasanella, whose story is told in Anne Broyles’s I’m Gonna Paint: Ralph Fasanella, Artist of the People, might have passed Abraham Cahan at a union meeting in New York! In addition to his remarkable story, told in an effective and engaging narrative, Victoria Tentler-Krylov’s illustrations manage to fill the pages with the same kind of color, vibrancy, and energy as Fasanella did in his own paintings, some of which are meticulously reproduced here by the illustrator. As is appropriate for a picture-book biography of an artist, the illustrations truly enhance the text and help make the story both visually compelling and inspiring.

Perhaps Ralph Fasanella, whose story is told in Anne Broyles’s I’m Gonna Paint: Ralph Fasanella, Artist of the People, might have passed Abraham Cahan at a union meeting in New York! In addition to his remarkable story, told in an effective and engaging narrative, Victoria Tentler-Krylov’s illustrations manage to fill the pages with the same kind of color, vibrancy, and energy as Fasanella did in his own paintings, some of which are meticulously reproduced here by the illustrator. As is appropriate for a picture-book biography of an artist, the illustrations truly enhance the text and help make the story both visually compelling and inspiring.

Born in 1914 to an Italian immigrant family, Ralph grew up on the streets. He taught himself to read by studying newspapers and learned about politics as he accompanied his mother to union meetings “and to the dress factory where she worked.” After a short stint in a Catholic reform school, Ralph became a trade union organizer.

Fasanella didn’t start drawing until he was 31. He taught himself how to paint by observing the works of famous artists in museums. Soon he was filling “giant canvases with precise details and bold colors that rippled out, like when a pebble is thrown into a pond.” He drew about his childhood in the 1920s, his father’s ice delivery horse and wagon, his mother’s work as a seamstress, and about the ordinary people and streets of the city. He also captured important events, such as the 1963 March on Washington. “Any good painting is a social statement,” he said. A major project was his creation of multiple paintings that captured one of the most significant labor strikes in US history. Entitled “Lawrence 1912—The Bread and Roses Strike,” it took three years to make, during which he lived at the YMCA in Lawrence, Massachusetts, and interviewed local folks about the historic event.

A page from Anne Broyles’s I’m Gonna Paint: Ralph Fasanella, Artist of the People.

Discovered by art collectors later in life, Fasanella’s paintings were eventually exhibited at galleries and museums. (His Bread and Roses painting was displayed in Congress’s Rayburn House Office Building for years.) His work was also shown in more modest surroundings, such as union halls and at least one subway station. An author’s note asserts that Fasanella “remained true to his roots” even after he became famous. “I have been a working man and a union man all my life,” Fasanella explained. “My paintings celebrate that. They’re about working people: what they do, where they go, and what their hopes and dreams are.’”

The helpful appendix includes more about the artist, a timeline of his life, a list of the moments in US history that Fasanella painted, a bibliography, and a list of other picture-book biographies of socially conscious 20th-century artists: Dorothea Lange, Jacob Lawrence, Gordon Parks, Diego Rivera, Ben Shahn, and Charles White.

If you think a “Cinderella story” includes a handsome prince, a fairy godmother, and a glamorous ball, think again. As told in Comet Chaser: The True Cinderella Story of Caroline Herschel, the First Professional Woman Astronomer, pioneer astronomer Carole Herschel was indeed forced to cook, clean, and keep house for her demanding mother. (She described herself as the “Cinderella of the family.”) But her escape came via her brother, William Herschel, who shared her passion for astronomy. Leaving her home in Germany, she joined him in England in 1772. At first, she learned to sing and performed in concerts with William. Then they built an astonishingly accurate telescope in their backyard, creating a groundbreaking chart of the night sky. They even converted a room in their home into a metal-casting workshop in order to build an even bigger and better telescope!

If you think a “Cinderella story” includes a handsome prince, a fairy godmother, and a glamorous ball, think again. As told in Comet Chaser: The True Cinderella Story of Caroline Herschel, the First Professional Woman Astronomer, pioneer astronomer Carole Herschel was indeed forced to cook, clean, and keep house for her demanding mother. (She described herself as the “Cinderella of the family.”) But her escape came via her brother, William Herschel, who shared her passion for astronomy. Leaving her home in Germany, she joined him in England in 1772. At first, she learned to sing and performed in concerts with William. Then they built an astonishingly accurate telescope in their backyard, creating a groundbreaking chart of the night sky. They even converted a room in their home into a metal-casting workshop in order to build an even bigger and better telescope!

England’s King George III initially recognized only William’s achievements. But when Caroline discovered a new comet in 1786, her own career was also launched. She, too, was awarded a salary to study astronomy. At a time when few women were even allowed to study science, Caroline not only broke barriers, she helped to establish astronomical observations and calculations for years to come.

Interspersed with pithy quotations from Herschel’s own writings, the narrative manages to make a complex story clear and easy to grasp, bringing both Caroline’s work and life into focus. The lovely illustrations, many of which were inspired by the Herschel Museum of Astronomy in Bath, England — the former home of Caroline and William — add context and atmosphere. Infused with blues, grays, and browns, they help to bring Caroline out of obscurity or, as the motto of England’s Royal Astronomical Society, which awarded her an honorary membership and a gold medal, says: “Let Whatever Shines Be Noted.”

Cyrisse Jaffee is a former children’s and YA librarian, children’s book editor, and a creator of educational materials for WGBH. She holds a master’s degree in Library Science from Simmons College and lives in Newton, MA.

Tagged: "I’m Gonna Paint: Ralph Fasanella Artist of the People", Abraham Cahan, Amazing Abe: How Abraham Cahan’s Newspaper Gave a Voice to Jewish Immigrants, Comet Chaser: The True Cinderella Story of Caroline Herschel, Norman H. Finkelstein, Ralph Fasanella, the First Professional Woman Astronomer, Vesper Stamper