Classical CD Review: “Letters From Gettysburg” — A Powerful Plea for Compassion

By Susan Miron

Letters from Gettysburg is an extraordinarily haunting five-movement work that elevates the experience of one man into a memorial to all victims of war.

In July 1863, during the first two days at the Battle of Gettysburg, some 46,000 men were killed or wounded. The men who died in the field were spared the agony of countless others; badly wounded and rescued, they would expire weeks later. This was the fate of Lt. Rush Palmer Cady of the 97th New York Volunteer Infantry or “Cronkling Rifles.” Hit by a bullet early on, he died twenty-three days later, on July 24, 1863, at the age of twenty-one.

In July 1863, during the first two days at the Battle of Gettysburg, some 46,000 men were killed or wounded. The men who died in the field were spared the agony of countless others; badly wounded and rescued, they would expire weeks later. This was the fate of Lt. Rush Palmer Cady of the 97th New York Volunteer Infantry or “Cronkling Rifles.” Hit by a bullet early on, he died twenty-three days later, on July 24, 1863, at the age of twenty-one.

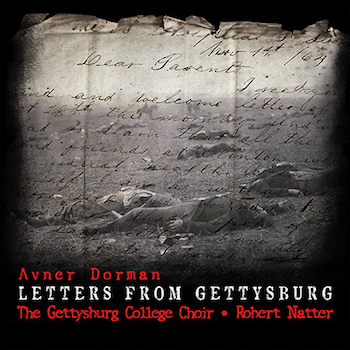

In the weeks before his death, Lt. Cady wrote four letters to his family, stoically communicating his “good courage” against severe pain. The fifth letter was penned by his anguished mother to her husband from her son’s deathbed. In his piece Letters from Gettysburg (Canary Classics), Israeli composer Avner Dorman sets this correspondence to music written for mixed chorus, baritone, soprano, and a top notch group of percussionists. The soldier’s words are unsurprisingly touching — in Dorman’s hands they become excruciating. I have listened to this ingeniously crafted piece a half dozen times and each time I have been moved anew, mesmerized by Dorman’s brilliant treatment of Lt. Cady’s words, and by the exquisite performances by soloists Amanda Heim and Lee Poulis, the Gettysburg College Choir, and the Tremolo Percussion Ensemble under the direction of Robert Natter.

Dorman’s choral score was commissioned in 2013 by the Gettysburg College American Civil War Sesquicentennial Planning Committee to mark the 150th Anniversary of the Battle of Gettysburg. The idea for Letters from Gettysburg arose from a conversation Dorman had with Peter Carmichael, director of the Civil War Institute at Gettysburg College, in which he suggested that the composer, who teaches at Gettysburg College, should consider drawing on words from the unpublished correspondence of a young soldier. This suggestion grew into an extraordinarily haunting five-movement work that elevates the experience of one man into a memorial to all victims of war.

In the album’s notes, Dorman is frank about his political intent:

I think that growing up in a country that is often at conflict and as a descendant of those who escaped persecution, these issues have always dominated my political and societal interests. My earliest significant work for orchestra, Ellef Symphony, for instance, deals with war and death, and the promise of another future; my first opera, Wahnfried, explores the rise of Nazism in the context of German nationalism and the Wagner family circa 1900. And my Prayer for the Innocents commemorates the children who were massacred in 2004 in the school siege in Beslan, Russia. I’ve always been drawn to texts that present the perspective of the individual within the context of war, which led me to Rush P. Cady’s letters, to his humanity, his heroism, his and his family’s pain inflicted by war.

The composer concludes that:

For me, the central lesson that can be learned from Letters from Gettysburg, is that, ultimately, conflict and disagreement hurts people and families. It’s much easier to fight over an ideology when we forget that the people who suffer by it are individuals and families – people we can all identify with. It’s so easy to cast a whole group of people as ‘the enemy.’ But we must remember that every person has thoughts, feelings, and loved ones. If we could only remember that, our political discourse today would become much more compassionate and empathetic.

This impressive CD also includes After Brahms: Three Intermezzos for Piano, which Dorman wrote for pianist Orli Shaham as part of her “Brahms Inspired” project. (The pair discuss the enterprise on You Tube in The Physics of Brahms). “I love the idea,” Shaham writes, “that Brahms is kind of a link in the chain that continues to speak across the centuries, that he channels the music that came before him and he continues to inspire composers to the present day. Dorman’s rethinking of two Brahms intermezzi (Op. 118, No. 1 and Op. 119, No.1) are wildly virtuosic. I will not be able to hear the originals without thinking of Dorman’s clever settings, which were startling at times, but satisfying. Shaham originally recorded these Brahms-inspired pieces in 2014 as part of a double-disc set for Canary Classics. The younger sister of her famous brother, violinist Gil Shaham (with whom she frequently collaborates), Orli is a very gifted pianist. Her performance here is exquisite.

The CD’s final piece, “Nigunim: Violin Sonata No. 3,” was also previously recorded for Canary Classics. Written by Dorman for Gil and Orli Shaham, this is a wildly demanding piece, an ambitious multicultural grab bag. The composer infuses his own made-up Jewish tunes, or nigunim, into a wide variety of cultural alternatives: traditional Arabic music, Georgian folk, Macedonian dances, and tunes from a Libyan synagogue. The Shahams’ performances are exhilarating, as one expects from these daring artists.

Susan Miron, a harpist, has been a book reviewer for over 30 years for a large variety of literary publications and newspapers. Her fields of expertise were East and Central European, Irish, and Israeli literature. Susan covers classical music for The Arts Fuse and The Boston Musical Intelligencer.

Tagged: Avner Dorman, Canary Classics, Gil Shaham, Letters from Gettsyburg, Orli Shaham