Classical CDs Review: Suppé Overtures, Bronsart and Urspruch Piano Concertos, and “Destination Rachmaninov”

Pianist Daniil Trifonov’s latest Rachmaninov album is magnificent; the Münchner Rundfunkorchester do right by Franz von Suppé’s overtures, and the Romantic Piano Concerto series continues to unearth gems.

By Jonathan Blumhofer

Franz von Suppé’s operettas may be all but forgotten today, but his overtures to them are incredibly durable. So a new recording (on BR Klassik) featuring the Münchner Rundfunkorchester (MRO) led by Ivan Repušic reminds.

At the heart of these eight selections — which includes Die schöne Galathée, Boccaccio, Banditenstreiche, and Pique Dame – is their irrepressibly fresh tunefulness. In a sense, all Repušic had to do here was give a downbeat, let the orchestra play, and not get in its way. He mostly does this and the MRO sounds largely wonderful throughout: there’s lots of rhythmic bite to their playing, the occasional florid roulades are all tossed off confidently, and the performances are marked by blazing color and good balances. Lots of spirited personality, too: this is an orchestra fully inhabiting the music, not one on autopilot in these light-music classics.

But Repušic isn’t entirely hands-off here, and that’s generally for the good. True, he broadens out Boccaccio’s final peroration, to rather anticlimactic effect. But he reins in the overtures’ more bombastic tendencies — especially their sometimes-insistent percussion riffs — and has a strong sense of character and phrasing in each. Thus, the obscure Die Frau Meisterin’s central waltz comes across with charming discretion; Leichte Kavaliere’s apogees and famous galop are energetic but never too emphatic; and Ein Morgen, Mittag, und Abend in Wien sings jubilantly (even if the cymbal player anticipates the final crash a bar too soon).

That mistake aside, this is a fine disc. You can still get Mehta conducting most of these pieces with the Vienna Philharmonic (on Sony) and Neeme Järvi’s got a more expansive survey of Suppé (on Chandos). But for spirit, playing, sympathetic conducting, and overall sound, this album’s a winner.

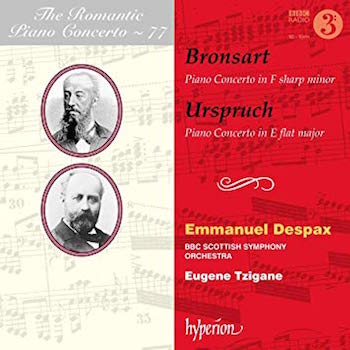

Hyperion’s The Romantic Piano Concerto series continues unearthing hidden (or missing) gems from the 19th– and early-20th-century piano-orchestra repertoire. The seventy-seventh installment pairs a couple of warhorses by Hans Bronsart von Schellendorf and Anton Urspruch.

Never heard of them? You’re not alone.

In his day, though, Bronsart was a big deal: the pianist to whom Liszt entrusted the premiere (and dedication) of his own Piano Concerto no. 2 and, afterwards, a respected conductor. Bronsart’s own Piano Concerto in F-sharp minor was written for his wife, Ingeborg, who was apparently a formidable pianist as well as an accomplished composer.

The Concerto’s three movements are in the typical fast-slow-fast mold and owe a large technical and rhetorical debt to the models of Liszt and Beethoven, with some echoes of Brahms and, especially in the slow movement, anticipations of Richard Strauss’s melodic style.

It’s a lovely piece, all the same, especially when played with the panache Emmanuel Despax brings to the solo part here. He’s got Bronsart’s style down cold, from the grandiose gestures of the slightly stodgy first movement, to the touching lyricism of the second and the playfully aggressive flourishes of the tarantella-finale.

Anton Urspruch’s Piano Concerto in E-flat major provides a nice counterbalance to the Bronsart. A younger contemporary of the latter’s with his own ties to Liszt (he was one of the great man’s later pupils), Urspruch’s Concerto is a truly epic work: the first movement clocks in at just over twenty-four minutes. It also imitates the Beethovenian concerto model, though Urspruch’s writing is generally more relaxed than fiery. The big opening movement boasts a kind of pastoral quality while the second offers an austere contrast, with a chant-like string melody countered by richer piano and woodwind writing. For the finale, Urspruch composed a spirited set of variations.

Despax plays the piece for all it’s worth, teasing out the rich, Brahmsian textures of the first movement and the zesty playfulness of the last. In the short middle one, he imbues the score’s rippling passagework with glinting color and a strong sense of melodic direction.

In both pieces, Eugene Tzigane leads the BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra in well-rounded and potent accompaniments. By any measure, these are unfamiliar pieces and, even if the orchestral writing is less challenging than the solo parts, the ensemble sounds like they’ve been playing them both forever: the handful of orchestral solos in the Bronsart are strongly done and the delicate, introspective moments in the Urspruch really sing.

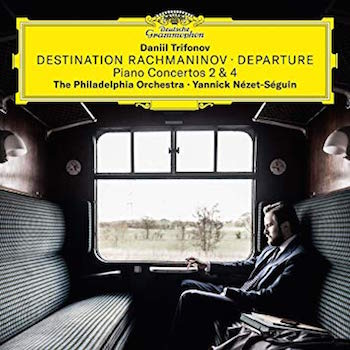

Few pianists alive or dead have as persuasive a way with the music of Sergei Rachmaninov as Daniil Trifonov. So it is with Trifonov’s new album, Destination Rachmaninov, a magnificent new recording (on Deutsche Grammophon) that features the Second and Fourth Piano Concertos plus three movements from Bach’s E-major violin partita in Rachmaninov’s piano arrangement.

As always, Trifonov’s technique is breathtaking. The textural clarity of his playing here is faultless: regardless of the rhythmic complexity or thickness of the counterpoint, nearly every note he plays tells with pristine clarity. So you can hear that the furious left-hand runs in the Second’s first movement are staggeringly precise, as are his articulations of the Fourth’s shifting rhythmic patterns.

Nor does Trifonov lose sight of the concerti’s underlying lyrical impulses: the outer movements of both may be plenty flashy, but they never lack for songfulness. Neither do the two slow ones, which here are each radiantly mellifluous (the Second’s, in particular, sounds truly like chamber music, so responsive and sensitive are the exchanges between soloist and orchestra).

Yannick Nézet-Séguin and the Philadelphia Orchestra accompany Trifonov in both concerti. This is an orchestra with a long Rachmaninov history and it tells in their playing, which is lustrous and rich-toned. The solos in the Second Concerto’s middle movement are (as noted above) beautifully played and the ensemble brings plenty of sardonic charm to the Fourth’s finale.

In the Partita transcription, Trifonov plays with pearly tone and incisive articulations. Nothing’s unduly weighed down: the Gavotte and Gigue dance with sparkling energy and precision, while the Prelude brims with sunny warmth. A strong continuation, then, of Trifonov’s ongoing Rachmaninov survey; the culminating entry with the remaining concertos ought to be something special.

Jonathan Blumhofer is a composer and violist who has been active in the greater Boston area since 2004. His music has received numerous awards and been performed by various ensembles, including the American Composers Orchestra, Kiev Philharmonic, Camerata Chicago, Xanthos Ensemble, and Juventas New Music Group. Since receiving his doctorate from Boston University in 2010, Jon has taught at Clark University, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and online for the University of Phoenix, in addition to writing music criticism for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette.