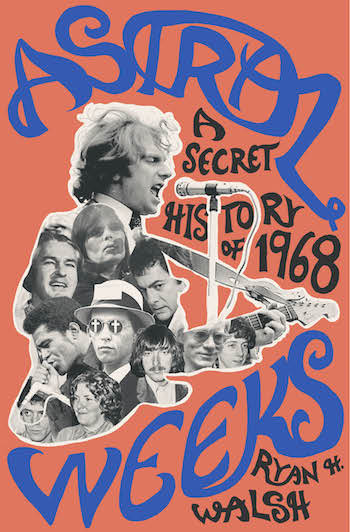

Book/Music Feature: “Astral Weeks: A Secret History of 1968”

Dedham native and Boston University graduate Ryan H. Walsh wanted to to learn more about his hometown-area connections to what he calls his “favorite album of all time.”

By Blake Maddux

Although I read a fair amount of non-fiction, I do not generally pick a single favorite book each year, let alone compile a top 10 list when the holiday shopping season comes around.

Recently, however, some books have hit the spot so squarely that they left all others in the dust. In 2016, it was definitely Joel Selvin’s Altamont (click for my Arts Fuse review). Last year, it was probably Good Booty by Ann Powers (click for my Arts Fuse interview).

I realize that it is only March, but I may already be able to declare the 2018 equal of such books.

Without the benefit having read Astral Weeks: A Secret History of 1968 by Ryan H. Walsh, I doubt that many people would have answered “Boston/Cambridge/Roxbury” to any of the following questions.

* Which city “served as ground zero for both the folk music revival and the origin of the American hallucinogenic revolution” in the 1950s and 1960s?

* Where did the cult leader to whom Rolling Stone dedicated stories in back-to-back issues and described as the “East Coast Charles Manson” live?

* The Velvet Underground is posing in front of a venue in which city on the back of its 1968 album White Light/White Heat?

* Which major urban center did not experience any rioting in the wake of the assassination of Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. thanks, in part, to public television programming?

* With which city’s bands did MGM Records attempt to replicate the psychedelic sounds of San Francisco?

* Where was Van Morrison living when he wrote and first performed the material that would comprise his classic 1968 album, Astral Weeks?

Actually, I did know that a James Brown concert in Boston resulted in many people being at Boston Garden on April 5, 1968. This is because I knew the least amount possible about a documentary called The Night James Brown Saved Boston. However, I was not aware the airing of the performance on WGBH kept many other people in their homes that night.

Moreover, I knew about the comically unfortunate attempt to transfer the sound of the Bay Area to the Bay State thanks to Adam Ellsworth’s recent Arts Fuse story about the “Bosstown Sound.”

Finally, I was mindful of Van Morrison’s having inhabited Cambridge in the late 1960s, but only because I heard it from someone in a bar or something like that. I didn’t research it any further, but the poem on the sleeve of Astral Weeks seemed to offer confirmation enough. After all, it contains the lines, “I saw you coming from the Cape, way from Hyannis Port all the way…I saw you coming from Cambridgeport with my poetry and jazz….”

(Astral Weeks is not an album that everyone who has heard of Van Morrison knows about. It does not contain any of his hits or radio favorites like “Brown Eyed Girl,” “Moondance,” “Domino,” “Wild Night,” or “Have I Told You Lately?” However, it is not exactly obscure, either. In 2001, more than 30 years after its release, it was certified gold for 500,000 sales, making it one of the seven entries in Morrison’s extensive catalog to have sold at least that many copies. Plus, Rolling Stone ranked it the 19th among its 500 Greatest Albums of All Time in 2012.)

Author Ryan H. Walsh. Photo: Marrisa Nadler

Dedham native and Boston University graduate Ryan H. Walsh had a different experience with Morrison’s cryptic, literally unsung words than I did.

“For years I’d looked at the back of that record, saw Cambridgeport and Hyannis, and thought, ‘Those are English places I’m not aware of,’” Walsh told me in a recent phone interview. “It was one of those like ‘does not compute’ kind of moments, because he’s from Belfast and these are places right around me. But that makes no sense.”

Walsh, 39, is familiar to fans of local music as the leader of the Boston Music Awards-winning band Hallelujah the Hills. However, his work as a journalist dates back to his days at BU.

“At film school, I was also the music editor for two years at the [Daily Free Press], so that’s where the journalism comes from,” Walsh said. “Early this decade, I started writing for the Phoenix, doing more long-form things. They all come together in this book: the writing, the film, the music.”

Walsh eventually became determined to learn more about his hometown-area connections to what he calls his “favorite album of all time.”

This resulted in his 2015 Boston magazine article called “Astral Sojourn.”

According to then-editor-in-chief Carly Carioli, who interviewed Walsh before a packed Brookline Booksmith basement on Tuesday, the story was one of the most liked, shared, and otherwise reacted-to pieces in the magazine’s history.

(Mayor Marty Walsh—no relation—declared Tuesday, the day of the book’s release, to be “Astral Weeks Day” in Boston.)

One of the many readers of “Astral Sojourn,” Walsh explained, was Penguin Press editor Ed Park.

“I was driving up to Vermont to play a show with my band. And we stopped at a gas station kind of in the middle of nowhere, but I still get reception. And I pull up my email, and there’s an email from an editor at Penguin. And it started with, ‘I know you must be getting a lot of messages from editors.’ That wasn’t true. I wasn’t fighting off editors, but I was glad to go along with that illusion! … He reached out to me because he loved the album and article. In fact, he used to have a reoccurring column for the LA Times called ‘Astral Weeks.’ … Eventually what we stumbled upon was using the city and the year as an anchor, and Van and Astral as an anchor, and then seeing where else we could kind of turn the camera’s eye and weave a kind of quilted story together.”

It turns out that Boston was as rich in the weirdness, drama, and culture that would define 1968 as more-focused-upon places like Berkeley, Greenwich Village, and Chicago were.

This all becomes clear as Walsh’s quilted story unfolds and reminds or informs readers of certain historical truths about Boston.

For example, the folk venue Club 47 (located in the space that Club Passim now occupies) was what helped make Boston the aforementioned “ground zero of the folk music revival.”

In fact, Walsh writes, “The endorsement of Cambridge, in particular Club 47, by artists like Joan Baez, Bob Dylan, and Dave Von Ronk was hugely important to Morrison—it was one of the reasons that Morrison chose to flee there.”

Moreover, counterculture heroes Timothy Leary and Richard Alpert—later Ram Dass—were professors at Harvard University and residents of Newton. (Leary was born in Springfield.)

Furthermore, The Velvet Underground played Boston 15 times in 1968, much to the delight of a Natick teenager named Jonathan Richman.

Not last and not least, there was the Fort Hill Community of Roxbury, lorded over by the former musician and self-proclaimed messiah Mel Lyman, who was featured on the cover of the December 23, 1971 issue of Rolling Stone and received a letter from Charles Manson while the latter was in prison.

[clickToTweet tweet=”The book ‘Astral Weeks: is not an effort to pick apart its namesake album song-by-song, word-for-word, and note-for-note.” quote=”Astral Weeks is not an effort to pick apart its namesake album song-by-song, word-for-word, and note-for-note.”] Nor is it an attempt on Walsh’s part to create a book-length version of Lester Bangs’s worshipful 1978 essay on Van the Man’s masterpiece.

An excerpt from the cover of Astral Weeks.”

Each of the book’s 11 chapters—several of which I have not even touched on the content of—is far more deliriously delicious than they would have been had Walsh taken either approach. Astral Weeks would have been an ideal way to describe the 52 individual units that comprised 1968 even if Van Morrison had not chosen it for the album that he released that year.

Readers of this book will learn an abundance about things they have never heard of—as Walsh himself said he did—and more about things about which they already know a great deal.

I do, however, have one major criticism of this secret history of 1968, and it is something of an unforced error on the author’s part.

I don’t want to require a spoiler alert to precede this piece, so I will not be too specific. Suffice it to say that on page 5, Walsh states his desire to resolve an issue that he claims Morrison biographers “tend to gloss over.”

Based on my possibly imperfect reading of the text, I am not certain that Walsh answers his own question. If he does, then the fact that other writers do not devote very much space (“a paragraph or a page,” the author told me) to it may be due to the fact that not much explanation is required.

As for Walsh’s having not interviewed Morrison for the book, anyone who knows anything about the boorish, mercurial singer-songwriter will know exactly what Walsh’s words to me mean: “It would have been interesting, but probably not helpful.”

Blake Maddux is a freelance journalist who also contributes to The Somerville Times, DigBoston, Lynn Happens, and various Wicked Local publications on the North Shore. In 2013, he received an MLA from Harvard Extension School, which awarded him the Dean’s Prize for Outstanding Thesis in Journalism. A native Ohioan, he moved to Boston in 2002 and currently lives with his wife in Salem, Massachusetts.