Concert Review: Linda J. Chase — “The City Is Burning”

Chase’s iconoclastic genre-crossing oratorio proceeds from dark to light, and wins its struggle for transcendence.

Composer Linda J. Chase. Photo: Susan Wilson.

By Steve Elman

Any artist who creates a work dealing with contemporary issues has to wrestle with essential purpose. Should she or he try to teach the audience, or preach to them, or open their thinking with provocative questions?

My preference has always been for art that asks questions. Polemics and didactics usually leave me feeling that the creator has gone beyond the sweet spot of art, and that his or her work shrinks in proportion to the specificity of the solutions proposed. I prefer to walk away from an artwork with my brain on fire, challenged by the artist to form my own solutions to the problems that he or she has nakedly exposed.

I recently had the chance to re-engage with one of the masterpieces of this type, Pablo Picasso’s Guernica, exhibited at Madrid’s Reina Sofia Museum, where it is the centerpiece of a multi-room exploration of the Spanish Civil War and its aftermath. Guernica’s monumental scale and its transformation of a massacre into abstractions of outrages and howls is not so much a call to action as it is a massive “WHY?” In its time, it spoke against the barbarity of the forces of Francisco Franco. Today, it transcends the events of its period. It speaks against the cruelty that persists in the human heart and cries out for the victims of every act of violence.

Linda J. Chase’s oratorio The City Is Burning is not Guernica, but it shares some of Guernica’s ambition, and it achieves a measure of Guernica’s transcendence. On October 29, I heard it in the New England Conservatory’s Brown Hall, a modest basement space that supplements NEC’s Jordan Hall upstairs. The City Is Burning engages with big themes, and this presentation was only marginally limited by its confines.

The music of the oratorio is eclectic, ranging from art song to free improvisation to subontinental raga to Latin to hymn tune and gospel, but this is what we would expect from a composer working in the Conservatory’s Contemporary Improvisation (CI) department, an academic enclave with the goal (among others) of knocking down borders wherever they limit full artistic expression. Chase handles all of the colors and transitions of her multi-part oratorio with aplomb, and again, this is only what we would expect of a member of the CI faculty. The real challenges to the composer in this work are in the meshing of message and music.

A glimpse of the October 29th performance of “The City Is Burning.” Photo: courtesy of Hankus Netsky.

Chase has chosen a broad range of texts, as she says, to reflect on “what it means to listen to . . . the quiet truth of the soul” in a time of “fragmentation, noise and interruptions.” The best of those texts are eloquent in themselves and her music frames them effectively. She has written supplemental material herself – less poetic, but given luminescence by her settings.

The words of the oratorio ask good questions. From Psalms 82 and 83, Chase chooses “Oh God, do not keep silence,” and “How long will you . . . show partiality to the wicked?” She freely adapts chapter 18 of Revelation about the destruction of Babylon: “The city is burning . . . In one hour, all the wealth you had has been laid to waste.” From poet Anne Porter, she selects a paraphrase of Psalm 87: “Who remembers now / The songs we sang in Zion?” In one of the most direct echoes of Guernica, she chooses a couplet from poet Dinos Christianopoulos: “They tried to bury us. They didn’t know we were seeds.” And she quotes poet Mary Oliver: “it is a serious thing / just to be alive / on this fresh morning / in the broken world.”

It’s a big verbal canvas, with plenty of opportunities for overreach, but Chase handles the material with admirable restraint. Possibly the greatest accomplishments of The City Is Burning are that the composer brings so many textual elements together so effectively in so many ways (spoken and sung), and that she gives the disparate pieces a strong sense of momentum that pulls the listener forward

One of her simplest unifying techniques is also one of the most powerful – the progression of the texts from darkness to light. She begins with a spare and somber meditation for flute, voice, and piano, followed by a catalog of world miseries from Zen philosopher-activist Thich Nhat Hanh – floods, droughts, wildfires, ice melt, growing deserts. Step by step, she moves the texts toward hope, ending with her own gospel song, “Lift Me Up,” praying to the creator to “Shake me up” and “Take away my sense of fear / That keeps me weak.”

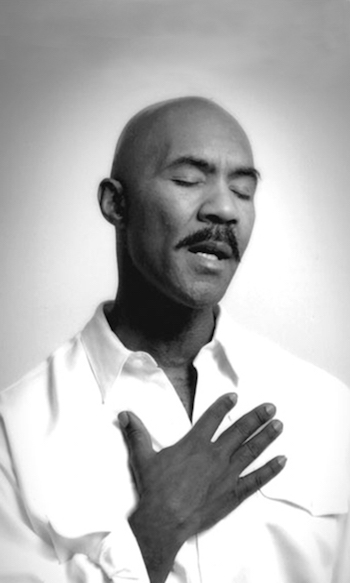

Singer-saxophonist Stan Strickland consistently lifted “The City is Burning” to higher ground. Photo: Stu Rosner.

Chase also rises to a musical challenge that mirrors the range of the texts – a 24-piece ensemble of players with an extraordinarily varied set of sound colors. She chose to use vocal soloists, a chorus of up to fourteen speaker / singers, five players of plucked instruments (gayageum [a Korean instrument related to the Japanese koto], two mandolins, acoustic guitar, and electric guitar doubling banjo), two violinists, two reeds (bass clarinet and soprano saxophone), a percussion team (orchestra bells, wooden wind chimes, gong, and jazz trap kit), piano, and bass.

The ensemble rarely performs at full strength during the oratorio. Instead, Chase breaks it into solos, chamber groups, duets, and choruses. In the performance I heard, the variety of sounds and sizes never felt cluttered or in conflict, thanks to a deeply sympathetic interpretation of the material by the Conservatory’s Contemporary Improvisation Ensemble, an add-a-part group composed of as many student players as are needed for a particular work.

There were several nominal “headliners.” Much of the narration was inspired by the ideas of Rev. Dr. Harvey Cox and designed for him as narrator. (Cox’s book-length meditation The Secular City has been profoundly influential on theological and secular thinking since its publication in 1965, and the title of Chase’s oratorio is arguably one more reference to that work.) Regrettably, health problems on that day prevented the 88-year-old Cox from filling the role Chase had in mind, but Douglas Cook was more than an adequate substitute for him, bringing to the work a resonant voice and a sensitivity to the meaning of the spoken words.

The other featured performer was Stan Strickland, whose multi-faceted career as saxophonist / flutist, vocalist, and actor has made him one of the most respected figures in the Bay State’s arts scene for more than forty years. Whenever he sang or played soprano saxophone, he carried The City Is Burning to higher ground.

But Chase did not put the full weight of the oratorio on either of them. Instead, the concluding number was given to the voice of Nedelka Prescod, an artist of such versatility that a few words simply cannot encompass all of her activities. As a singer, educator, and activist, she is, at a relatively young age, becoming one of those area performers whose very presence brings a special electricity to any musical situation, and in her reading of “Lift Me Up,” she seized the final moments and made them incandescent.

Individual members of the Contemporary Improvisation Ensemble were called on to step into and out of the spotlight, sometimes only for a few seconds, but many of their solo contributions left outsize impressions. Baritone Sam Jones was consistently moving and elegant as a singer, and he had one of the best spoken moments in his solo recitation of Joanna Macy’s text “Active Hope.” Vocalist Grace Ward, who usually accompanied herself on bass, was often paired with Jones and their voices blended superbly. Do Yeon Kim, who plays the gayageum, demonstrated that she is expanding her instrument’s range in the great traditions of NEC iconoclasm, using it for sound effects and clusters as well as playing it traditionally. Violinist Emma Gies was featured in a solo drawn directly from Hindustani traditions, performed on the floor in traditional posture. Daniel O’Brien had a sumptuous feature on bass clarinet. Bassist Chris Rathbun, a veteran of the local scene, stepped in as a sort of guest member of the ensemble to provide crucial support in “Calling Out,” a full-band piece in the George Russell tradition. Drummer Taichiro Ei and especially pianist Unchu Pyon, though only briefly featured, were the rocks on which almost everything was founded, and they showed extraordinary versatility. And Chase gave herself several meditative moments on flute, showing off a beautiful tone.

The heart of Chase’s oratorio is gospel music, and those numbers were the most moving and memorable. I mentioned Prescod’s performance in “Lift Me Up,” but Strickland’s “Come away, the city is burning” was nearly as powerful. Gospel touches added resonance to “Seeds of Peace” and “Just Remember Your Light” and set the stage for the conclusion.

In my view, there are only two major missteps in the oratorio. Chase’s “Jeremiah” calls for projections, wandering reciters, and a live-action sequence of a stylized human sacrifice to be layered on top of the music, and I think these elements – although she intends them to be somewhat confusing and disruptive for the audience – go too far toward the polemic and upset the balance of the work. The second misstep was the composer’s choice to cast herself as the reader of Mary Oliver’s beautiful poem, “Invitation.” This is a crucial moment, just before the full optimism of “Lift Me Up,” and I felt that the text deserved a more nuanced reading.

Singer Nedelka Prescod has a commanding presence, and she brought “The City is Burning” to a transcendent climax.

But these cautions should not be taken as denigration of the power of The City Is Burning. Chase’s strengths as a composer and as a manager of musical forces are obvious. More importantly, she displays the gift of melody, something that listeners feel lucky to encounter, something that lives in the bones long after the music itself has died away.

More:

The City Is Burning was commissioned by the Old Cambridge Baptist Church, where its original version premiered on March 12, 2017. Linda Chase extensively revised the work for the October 2017 performance at NEC, which was so different from the original version that it might be considered a “second premiere.” She has kindly provided me with notes on the revisions, and I have edited them here for the record:

“At OCBC, Dr. Harvey Cox was the guest narrator, with Stan Strickland and pianist George Russell, Jr. as additional guest artists. The OCBC choir was directed by Thomas Jones, and two vocal soloists, Nadia Raies and Milu Farras Ballester, came from Berklee.

“Because I had a whole new group of performers to work with, I added a lot to the original structure of The City Is Burning for the NEC performance. I composed four new pieces and rearranged others especially for them.

“I added an improvised duet to the opening song, ‘Refuge,’ featuring Emma Gies, with my own accompaniment on flute; both of us consciously drew on Hindustani tradition for our improvisations. The second piece at the NEC performance, ‘The Bells of Mindfulness,’ is completely new; I put some performers in the balcony of Brown Hall to provide an additional acoustic element. ‘Calling Out,’ with a Rūmi quote (‘Keep walking but not the way fear makes you move’), is also new. ‘We Have Forgotten’ was originally written as a congregational hymn; I rearranged it to feature Grace Ward’s voice and the chamber ensemble of voices and instruments. The following number, ‘Song for the Turtles in the Gulf,’ is another new addition.

“I revised the music for ‘Jeremiah,’ extending the harmonies and melodies and adding a vocal solo for Matthew Shifrin. Some of the extra-musical elements for this section were also re-set. The original readings of newspaper texts were only in English, but in the NEC performance we added texts in Spanish, Cantonese, and Mandarin. The video elements (a collage of advertisements and news reports from television broadcasts) were created and manipulated by Jon Dewitt and Adam Tuch and projected on a large screen.

“Finally, ‘Don’t Go Back to Sleep’ was one more addition, developed collaboratively with my Interdisciplinary Ensemble.”

A recording of The City Is Burning can be downloaded via instantencore.com, which has many recordings of other NEC concerts as well. The app (available to Google Play and Apple Store users) can be accessed here.

The next performance of a work by Linda Chase will take place on December 3, when she and Contemporary Improvisation chairman Hankus Netsky join an ensemble of CI musicians in Hope is the Hardest Love we Carry, a setting of contemporary poetry by Jane Hirschfeld and ancient Japanese poems in translations by Izumi Shikubu and Ono no Komachi. Hirschfeld herself will be present to read her texts. That concert takes place at 2 p.m. in Remis Auditorium at the Museum of Fine Arts.

Landscape Music provides an informative website with more information about Linda Chase and her work.

The next Contemporary Improvisation concert takes place in NEC’s Jordan Hall (at no cost!) on November 13 at 7:30 p.m.. It will be an evening of interpretations of the songs of Kurt Weill and Bertolt Brecht – and if past CI concerts are any prediction of musical value, it should be kaleidoscopic in its scope and well worth your hearing.

And, for anyone interested in the crosscurrents of classical and jazz, NEC is presenting a tribute to the late Gunther Schuller at Jordan Hall on Friday, November 17 at 8 p.m. The program will include two of Schuller’s greatest Third Stream pieces, “Transformation,” and “Variants on a Theme of Thelonious Monk [Criss-Cross].”

Steve Elman’s four decades (and counting) in New England public radio have included ten years as a jazz host in the 1970s, five years as a classical host in the 1980s, a short stint as senior producer of an arts magazine, thirteen years as assistant general manager of WBUR, and currently, on-call status as fill-in classical host on 99.5 WCRB since 2011. He was jazz and popular music editor of The Schwann Record and Tape Guides from 1973 to 1978 and wrote free-lance music and travel pieces for The Boston Globe and The Boston Phoenix from 1988 through 1991.