Book Review: “Never A Dull Moment” — Rock Apotheosis

Was 1971 greatest year in the history of rock? Read this delightful book and be prepared to argue.

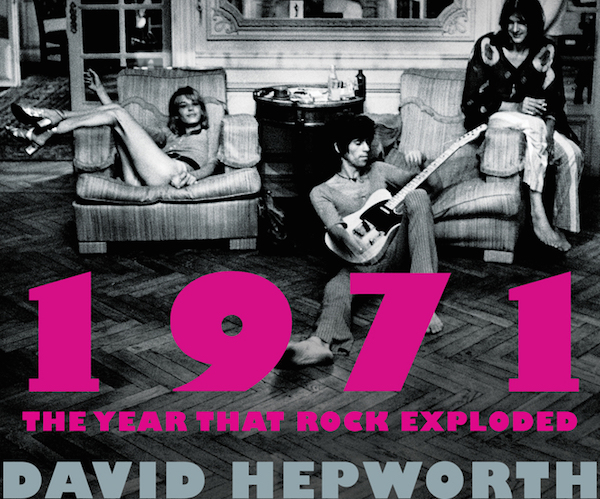

Never a Dull Moment: 1971 — The Year That Rock Exploded by David Hepworth. Henry Holt and Co., 320 pp. $30.00 (hardcover)

By Blake Maddux

The 1970s is the Rodney Dangerfield decade of twentieth-century American history.

With the resignation of a president, a lost war, gas lines, leisure suits, and disco littering the political and cultural landscape, it just doesn’t get any respect.

According to a new book by veteran music journalist David Hepworth, however, these 10 years started off exceptionally well by music standards. In fact, he contends on the first page of said book that 1971 was “the busiest, most creative, most innovative, most interesting, and longest-resounding year” of the rock era.

Strangely, the title of Never a Dull Moment is the same as that of a Rod Stewart album that was released in 1972.

But never mind that now. The more pressing matter is whether the book is as convincing as it is impossible to look up from.

Paraphrasing the nineteenth-century British imperialist Cecil Rhodes, who said that to be born an Englishman was to win “first prize in the lottery of life,” Hepworth (himself a Brit) writes, “I was born in 1950. For a music fan, that’s the winning ticket in the lottery of life.”

Despite my being more than a quarter-of-a-century younger than Hepworth, I can relate to his enthusiasm. In fact, I wished as a kid that I had been born in 1951, the year of my mother’s birth, so that I could have grown up on The Beatles, The Rolling Stones, The Kinks, The Beach Boys, etc.

While few if any will question the quality of the popular music which Hepworth and his contemporaries were present at the unveiling of, the author acknowledges that it will not take long for his readers to “raise a skeptical eyebrow” regarding his elevation of 1971’s output. After all, everyone has a fondness and deep connection to the soundtrack of his or her most impressionable and carefree years of life.

However, “There’s an important difference in the case of me and 1971,” Hepworth confidently asserts. “The difference is this. I am right.”

As raised as the aforementioned skeptical eyebrow might be, let us begin by giving Hepworth some of the more or less obvious benefits of the doubt.

First, if he were convinced that the most significant year in rock had to have happened during his youth, he could have chosen one of several other worthy years. After all, human beings are significantly prone to the effects of the music that they hear during their first, say, 25 years of being alive. Giving that for Hepworth this would have included all of the 1960s and half of the 1970s, he had myriad choice years from which to select. Thus, he must have had his well thought-out reasons for picking the one that he did.

Second, although he sometimes uses the more inclusive term “popular music,” he refers specifically to “rock” in the title. As Hepworth sees it, the “pop era” ended on New Year’s Eve 1970, when Paul McCartney began the legal proceedings to disconnect himself from The Beatles. The next day, January 1, 1971, was “[y]ou might say…the first day of the rock era.” Therefore, in narrowing down his options, the author chose to focus on the post-Beatles epoch, thereby ruling out 1966, when some of the greatest records by the greatest artists of the ‘60s came out.

Finally, let us remember what some of the massively popular albums of 1971 were: Carole King, who “invented the album business,” released Tapestry, which was “destined to sell in quantities nobody had previously thought it possible to sell.” Led Zeppelin’s fourth album “put them into a commercial category that neither the Beatles nor the Stones ever reached.” Sticky Fingers was “the Rolling Stones’s most influential album.” Marvin Gaye’s What’s Going On “changed people’s expectations of a Motown album.” People viewed George Harrison et al’s The Concert for Bangladesh as having “elevated pop above its tawdry history into something altogether finer and more noble.” There’s a Riot Goin’ On by Sly & the Family Stone, Hepworth opines, “remains the least tidy, least house-trained albums that ever dominated the number one spot on the Billboard post and soul charts for weeks on end.” (And there was American Pie by Don McLean.)

The popular but not quite massively so offerings included Just as I Am by Bill Withers, Hunky Dory by David Bowie, Joni Mitchell’s Blue, Pink Floyd’s Meddle, Funkadelic’s Maggot Brain, and Can’s Tago Mago.

Plus, there were the ones that practically no one heard at the time, including Nick Drake’s Bryter Layter, and that were recorded but not released until later, such as the first songs by Memphis’s Big Star and Boston’s The Modern Lovers.

So while few if any will deny that many great and hugely popular records came out in the titular year, the same readers could rightly question Hepworth’s assertion that it all amounts to something not ever otherwise equaled.

Take, for example, his claim that the year in question “would see the release of more influential albums than any year before or since.” Even if one grants that, it is debatable that more of the most influential albums appeared in 1971.

Yes, Nick Drake — whose “music lives in the mainstream as a signifier for ‘alternative’” — released an album. However, it was his second one and not his indisputably best or most widely regarded one.

Hepworth also writes, “Very little has happened with the Stones since that summer that is all that interesting musically.”

Really? Not even the following year’s double album Exile On Main St., which many consider to be the band’s best and — as against the author’s claim about Sticky Fingers — most influential record? (Granted, Hepworth does guard himself against this criticism a bit by writing, “If you went to see them today and their repertoire didn’t go beyond 1972, you’d still feel like you’d got the Stones.”)

Furthermore, Never a Dull Moment contains the assertion that “Who’s Next sits at the center of 1971’s claim to be the most perfect moment in the short history of rock and roll, and with each passing year that claim grows stronger” and that it “continues to be played, enjoyed, and pilfered long after the likes of Tommy and Quadrophenia have grown tiresome.”

Remember Hepworth’s “I am right” statement? Well, in saying that, he forfeited the defense that any of the book’s conclusions were just his opinion. Thus, he needs to support himself with facts, especially with regard to what he believes to be the crowning musical achievement of 1971. What he writes about The Who is clearly based on his personal preference and experience rather than an uncontroversial and widely held sentiment.

It is fine if he honestly feels this way, but it can hardly be said to buttress his case considering that there are surely many who disagree.

Finally, there is the small matter of the album that Hepworth describes as “the 1971 recording that has had the most impact on subsequent generations of music makers.” One would think that a recording of such stature, not to mention the band that recorded it, would merit more than just a single perfunctory paragraph. After all, the album that Hepworth says is arguably “the most influential record to come out of 1971” gets, along with its creator, several pages of discussion.

But oh what a delightful book this is.

Who knew that The Allman Brothers Band’s “Whipping Post” was the original “Free Bird”? That rather than being “richer than you could possibly imagine,” The Rolling Stones were actually “poorer than you’d think”? That alt-country pioneer Gram Parsons and punk forefather Jonathan Richman bonded over the Louvin Brothers? Or that the session bassist Herbie Flowers got paid the same paltry fee for his “immortal” work on Harry Nilsson’s “Jump into the Fire” and Lou Reed’s “Walk on the Wild Side”?

Irrespective of whether one concurs that “it never got any better than 1971,” one is sure to nod in agreement with Hepworth’s overarching idea that all bets were off in a world that included the abhorrent vacuum left by The Beatles and the several dozen of the right people who had heard The Velvet Underground. For example, Roxy Music carved out its own well-fortified niche along the spectrum demarcated by these two extremes and demonstrated, before they even released an album, that “authenticity and sincerity were no longer self-evident virtues” and that “it was possible for things that were plastic and fake to be just as admirable.”

Granted, not all who enjoy and appreciate Never a Dull Moment are obligated to agree with it. But they should keep something substantially consequential in mind: in the time that it took the Earth to make this particular trip around the sun, David Bowie released Hunky Dory (probably my personal favorite of his) and wrote the material for The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars.

Thus, as Hepworth writes, “If all we knew of David Bowie was what he did in 1971, it would be more than enough.”

Blake Maddux is a freelance journalist who also contributes to The Somerville Times, DigBoston, Lynn Happens, and various Wicked Local publications on the North Shore. In 2013, he received an MLA from Harvard Extension School, which awarded him the Dean’s Prize for Outstanding Thesis in Journalism. A native Ohioan, he moved to Boston in 2002 and currently lives with his wife in Salem, Massachusetts.

Another great review Blake! Can we all agree though that no-one is allowed to write another book about how Year X is the most important/best/greatest year in rock for at least 5 years? It’s become the book-length version of click bait.

Thanks Adam, and good idea! Several years ago, a book called 1969: The Year Everything Changed was published. Less than six months later, along came one titled 1959: The Year Everything Changed.

Having been in this business for at least this long, I have an aversion to opinionated summaries about what in popular music in most significant. Nevertheless, your review has got me hunting for the book so I can catch up. As they say: “if you you can you remember the 60’s you weren’t there.”

The book reminds of another – Pictures at a Revolution: Five Movies and he Birth of the New Hollywood that makes a pretty good case for that claim.

All in all this was good summing up with great links! Well done.

Thanks Tim. I thought that I had replied to your comment before, but better 11 months late than never!