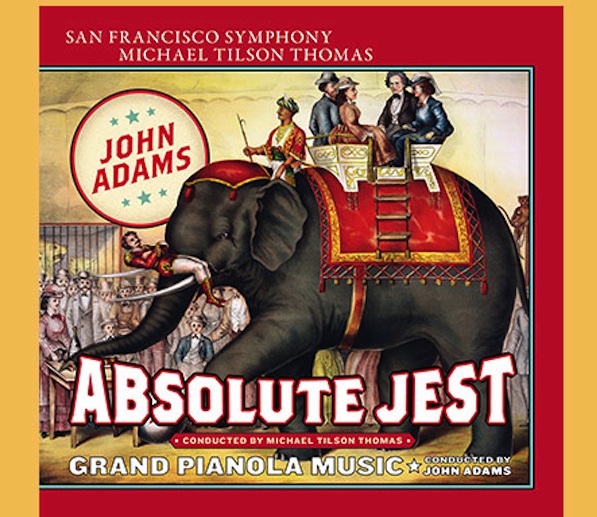

Classical CD Reviews: John Adams’ “Absolute Jest” (SFS Media); Alexander Melnikov plays Schumann (Harmonia mundi)

John Adams’ Absolute Jest is a sheer blast of fun, wildly inventive and, at its best, a vertiginous collage of the familiar organized in strange, unpredictable ways.

By Jonathan Blumhofer

Let’s call it “The Trickster Album”: in his note about his 1988 piece, Fearful Symmetries, John Adams discussed a tendency in his music of following up serious musical ruminations (in that case, Nixon in China and The Wound Dresser) with scores that are impish, darkly humorous, and wry. It’s one of the characteristics that, at the time, helped set Adams apart from many of his contemporaries and, as the San Francisco Symphony’s (SFS) new recording of his Absolute Jest and Grand Pianola Music attests, it still does.

Absolute Jest, Adams’ 2012 score for string quartet and orchestra, is one of an increasing number of recent Adams pieces that owes an unambiguous debt to Beethoven: its materials are drawn primarily from the string quartets opp. 131 and 135, the Grosse Fugue, and the Waldstein Sonata. It wears that liability lightly, though, and perhaps the most striking takeaway from the piece is how easily it integrates the character of Beethoven’s style into an otherwise wholly contemporary orchestral fabric. Yes, there’s a remix quality to it, with fragments of various Beethoven quartets appearing in sundry textures in and out of sync with the orchestra. But Adams has such a masterful command of this sort of musical context that everything feels utterly natural and appropriate.

And that technique helps compensate for the moments around the middle of the piece when it seems to lose its way and meander a bit. Thankfully, those passages are relatively few and short. For the most part, Jest is a sheer blast of fun, wildly inventive and, at its best, a vertiginous collage of the familiar organized in strange, unpredictable ways (like the hallucinogenic setting of fragments of the Grosse Fugue in the fourth movement). It may run a bit shallow, expressively, but it’s music that doesn’t seem to be trying to be too profound in the first place, not that it needs to be: in its cleverness and high energy, Jest makes a brilliant and welcome contrast to the only other repertoire work for string quartet and orchestra, Elgar’s restrained and nostalgic Introduction and Allegro.

There’s no faulting this performance. The SFS and music director Michael Tilson Thomas dig into Adams’ rhythmically tricky, texturally pellucid score with great care and energy and the St. Lawrence String Quartet sounds like they’re having a ball with their rollicking parts.

The same qualities apply to the Adams-led reading of Grand Pianola Music that rounds out this album. Preceding Jest by thirty years, Grand Pianola Music is also colored by the long shadow of Beethoven, most notably the “Emperor” Concerto. Scored for two solo pianos, winds, brass, percussion, and three amplified singers, it proved controversial at its 1982 premiere, though, as this performance demonstrates, it’s aged extremely well.

At the root of the piece is Adams’ gleeful embrace of tonal and Minimalist gestures – especially sweeping, etude-like arpeggios — that give the score a misleading simplicity. And, while it proclaims its apparent facileness with abandon (just listen to the finale, “On the Dominant Divide,” with its shameless swinging back and forth between tonic and dominant harmonies underneath a pop-like chorus, for a sense of this), the fact is that, beneath the shiny exterior, Grand Pianola Music is a built on a solid, musical foundation.

At least that’s how it sounds in the hands of pianists Orli Shaham and Marc-Andre Hamelin, who really find and make something of their highly involved, if relentlessly triadic, solo parts. Adams has been faulted (most memorably in the late ’80s by The New York Times) for his extensive use of arpeggios, but in Grand Pianola Music they function in a similar way as they do in Beethoven, namely as the scaffolding of the music’s expressive aim and it’s the job of the pianists here to make them sing. Shaham and Hamelin manage that beautifully and with lots of heart, especially in the second half of Part 1.

Synergy Vocals delivers a clear, energetic account of the score’s sung part that’s, on the whole, better balanced with the rest of the ensemble than the singers in either of the two major recordings of this piece already on the market. And Adams draws a rhythmically vital, impressively lyrical reading of the score from the SFS.

The recorded sound, as is typical of SFS Media productions, is clear and very nicely balanced between pianos, voices, and orchestra in Grand Pianola Music. In Absolute Jest, the quartet and orchestra generally blend well, though there can be a scrappy quality to the overall sound from time to time, perhaps owing to the challenge of capturing the intimacy of the quartet and the spaciousness of the orchestra that’s typical of this genre. Audience noise is minimal in both works, which were recorded live.

*****

Perhaps it was inevitable that, after the unmitigated triumph of the first installment of Harmonia mundi’s Schumann trilogy with violinist Isabelle Faust, cellist Jean-Guihen Queyras, and pianist Alexander Melnikov each performing one of the Schumann concerti (Arts Fuse review), the second volume in the set would see some falling off. It does that and then some: the recording, or at least the half of it featuring Melnikov playing the Piano Concerto on a fortepiano, is a significant disappointment.

The disc’s biggest problem is the fact that Melnikov’s fortepiano simply sounds wimpy and emasculated in this music. His playing is texturally clear and technically proficient, but wanting in color and muscle. The first two movements don’t really add up to much. Neither does the finale, which, taken at (or close to) Schumann’s original tempo marking, suffers from the added problem of sounding deliberate and cloddish.

The Freiburger Barockorchester, which worked so well with Faust in her account of Schumann’s Violin Concerto in the first installment of this series, again delivers a lively, rhythmically alert accompaniment. But many of the qualities that worked so well in the Violin Concerto don’t translate to the Piano Concerto. Schumann’s scoring of the latter includes several exposed passages for strings, especially (in the second movement) for viola and cello in their upper registers. The less forgiving tone of the gut strings makes these sections sound strained and tentative. The finale, overall, is very choppy. And, to top everything off, there’s a jarring discord (to these ears it sounds like a major and minor triad simultaneously juxtaposed) around the three-minute mark in the finale. Suffice it to say, nobody’s reputation is really enhanced here.

But the second half of the album is given over to Schumann’s Piano Trio no. 2 in F major and the performance is a gem. Faust and Queyras join Melnikov in an urgent, expressive account of the piece and just about everything clicks, from the punchy, nervous accents in the first movement to a deliciously balanced account of the busy melodic writing in the swooning second movement. The third movement is about as graceful and lyrical as you might hope it to be, while the finale is pensive and playful in equal measure.

Jonathan Blumhofer is a composer and violist who has been active in the greater Boston area since 2004. His music has received numerous awards and been performed by various ensembles, including the American Composers Orchestra, Kiev Philharmonic, Camerata Chicago, Xanthos Ensemble, and Juventas New Music Group. Since receiving his doctorate from Boston University in 2010, Jon has taught at Clark University, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and online for the University of Phoenix, in addition to writing music criticism for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette.