Music Interview: Inside Veteran Folk Singer Tom Paxton

“My idol was Pete Seeger, even before I moved to the Village. He still is.”

Cover art of Tom Paxton’s latest CD.

By Glenn Rifkin

For those of us lucky enough to catch the folk music wave of the 1960s, the impact was everlasting. Today, the worn vinyl albums recorded by Peter, Paul & Mary, Bob Dylan, Joan Baez, Phil Ochs, Tom Rush, Joni Mitchell and a host of others are most likely hidden away in a closet or attic, but the music is etched deeply into our emotional jukeboxes. In that pantheon, the name Tom Paxton conjures up a troubadour whose silky voice, sweet guitar picking, and evocative songs put him amongst the folk greats of the time. He performed his own iconic songs such as “The Last Thing on My Mind,” “Whose Garden Was This?” “Ramblin Boy” and “The Marvelous Toy,” and his prolific output provided songs for a who’s who of performers, from Dylan to John Denver, from Judy Collins to Willie Nelson.

Having arrived in Greenwich Village in 1960, Paxton, a devotee of Pete Seeger and Woody Guthrie, immersed himself in the emerging coffee-house folk music scene. He shared an apartment with Noel Paul Stookey just as Stookey was teaming up with Mary Travers and Peter Yarrow, and he spent long evenings at the Gaslight Café, a famed coffee shop on MacDougal Street, where he was a featured performer alongside the likes of Dylan, Phil Ochs, Eric Andersen, Dave Van Ronk, and Mississippi John Hurt. The soft-spoken Paxton’s contribution in this era of the singer/songwriter was huge; he wrote a vast collection of original folk songs and protest ballads. Van Ronk said that though Dylan is usually cited as the founder of the new song movement, “the person who started the whole thing was Tom Paxton. He tested his songs in the crucible of live performance.”

Paxton’s popularity waned in the 1970s after he and his wife Midge decided to move out of New York City to East Hampton on Long Island in order to raise a family. But though his career veered away from the spotlight, his songwriting and performing continued unabated for more than half a century. Sadly, after 51 years of marriage, Midge Paxton died in 2014. At age 77, Paxton has just released his 62nd album, Redemption Road, which is dedicated to his late wife. He is on his final tour and will be performing at the Amazing Firehouse in Framingham, MA on Saturday, June 13. He will also be performing on October 3 at the First Parish Church in Cambridge, sponsored by Passim.

ArtsFuse: What is all this about you retiring?

Tom Paxton: I’m going to stop touring after November. It has been 55 years and the airports and hotels and everything finally got me down. I don’t want to do it anymore. I still love performing so I’m not retiring. I’ll still do some festivals and some one-off appearances, but no more tours. I think I’m paid up at this point. And I’ll always be writing songs.

AF: Your career seemed to lose some momentum after the ’60s. What happened at that point?

Paxton: I think the quiet came from the fact that I was starting a family. We were living on 11th Street in the Village. I still remember when Jennifer (his first daughter) was about a year old, Midge came back from taking her for a walk in the park and she noticed soot around Jennifer’s nostrils and she said, “That’s it, we’re out of here.” We moved to East Hampton around 1967. It was not a shrewd career move. The shrewd career move would have been to stay in the middle of things in the Village. But we weren’t thinking in those terms. Jennifer came first.

AF: But you never stopped working.

Paxton: No. I continued to record. I left Elektra Records, which was also not a smart thing to do. But I spent ten years working steadily. I was always working in England and still making a nice living. But I wasn’t part of the buzz.

AF: What are your most vivid memories of the Village scene in the ’60s?

Paxton: Well, I saw Inside Llewyn Davis (the Coen brothers 2013 fictional account of the early folk scene in New York) and thought it was a very good movie. But it missed the laughter. We laughed our asses off and had a lot of fun with one another. Llewyn Davis is a grim guy and that was a grim movie. I’m not faulting the filmmakers. But my memories include the period’s artistic excitement. There was so much good music going on and we were all growing as musicians and writers and performers.

AF: How do you think it compares to the scene today?

Paxton: We had something they don’t have now, much to my dismay. They don’t have the stages we had. The young performers of today have to be as talented as we were, but we had a place to get up and log the hours in front of people. It is like pilots have to spend a certain number of hours in the air; a performer needs a certain number of hours on stage. We had that. It was going, night after night.

AF: Describe the scene.

Paxton: It was exciting, fun I would get to the Gaslight around 7. People would start showing up and we’d have six guys on the bill. You would each get three-song sets. It was perfect training. Six or seven times a night, you learned how to start a show, what to do next, and how to get off. Beginning, middle, and end — over and over. We had an upstairs room where we stored our instruments. We had a poker game that went on continuously and a speaker in the room so we could hear the show. You knew when you had to go down to perform, so you cashed in your chips, got ready to go on, and then after, you’d come back and get back in the game.

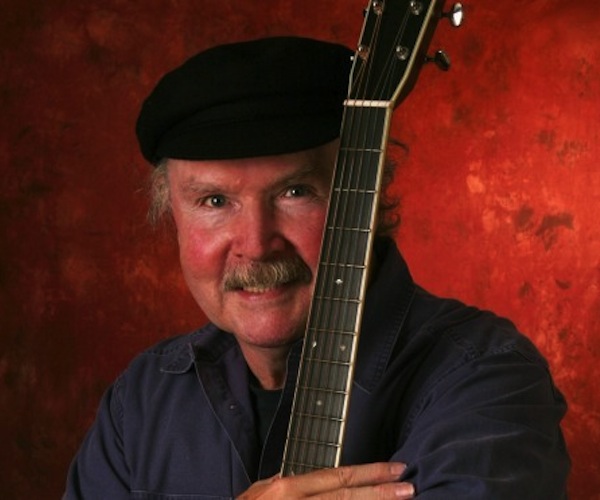

Tom Paxton — “we laughed our asses off and had a lot of fun with one another.” Photo: Michael G.Stewart.

AF: And you were rubbing shoulders with some serious talent.

Paxton: Wavy Gravy (who was the poetry director of the Gaslight and later, an iconic figure at Woodstock) had a portable typewriter up in the room. I showed up early one night and Dylan was taking a piece of paper out of the typewriter. He had just written something. I said, “What are you writing?” so he showed me and asked “What do you think?” I read this thing that was at least six or seven pages long. I said, “This is fabulous.” He said “What do you think I should do with it?” I advised, “For God sakes, put a tune to it. You could probably get 25 bucks from a poetry magazine but you have a song.” The next night, he sang it for the first time. It was called “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall.” Now, when I hear it and it gets into the sixth minute, I think “Jeez, what was I thinking, me and my big mouth.” I’m only kidding. I love the song. It’s a fantastic song.

AF: You arrived there before most of the new folk scene got started.

Paxton: When I got there in 1960, the Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem were the hottest thing in the Village. They hadn’t broken nationally yet. In 1960, you had the end of the previous generation, people like Oscar Brand, Jean Ritchie, Ed McCurdy, and Cynthia Gooding were being supplanted by us young guys. We didn’t think of it that way. We thought they were great and we loved them. But they weren’t in the coffeehouses. They had moved up to the concert halls. I was living with Noel Stookey then and I was kept awake many a night while he and Peter worked on the guitar parts. They were very anal about it, going over and over the guitar parts.

AF: Did you have an idol and a mentor?

Paxton: My idol was Pete Seeger, even before I moved to the Village. He still is. My mentor was Milt Okun, who became my music publisher for fifty years. He was the musical director for the Chad Mitchell Trio, Peter, Paul & Mary, John Denver, and too many more to name. As an arranger and producer, he was a very important fellow and one of the sweetest, nicest people you could meet. Most importantly, he was a sucker for my jokes. He’s still with us, in his 90s, living in Beverly Hills.

AF: How did he impact your career?

Paxton: I was picked to replace one of the original members of the Chad Mitchell Trio but it didn’t work out. My voice didn’t blend in properly. But during a rehearsal break, I sang “The Marvelous Toy” for them and they loved it. It became the only hit they ever had. More importantly, I became the first person signed by Milt’s new company, Cherry Lane Music. I was incredibly lucky. I was writing a lot of songs and he was working with lots of people and he would put these songs on quite a few of their albums. A lot of people including John Denver, Peter, Paul & Mary, and others, recorded my songs. It got me off the ground in many ways, including financially. I started getting actual royalty checks, which is hard to do.

AF: Now that you are leaving the road, how do you look back on your career?

Paxton: I’ve had a career that I’m happy with. I don’t look back and think I made wrong choices. I acknowledge that I made some choices that did not make business sense. But I don’t regret them.

Glenn Rifkin is a veteran journalist and author who has covered business for many publications including The New York Times for more than 25 years. Among his books are Radical Marketing and The Ultimate Entrepreneur. His efforts as an arts critic and food writer represent a new and exciting direction.