Film Review: You Can Go Home Again (If You’re a Star)

What happens when someone performs at the highest possible level of an art form and then has to give it up?

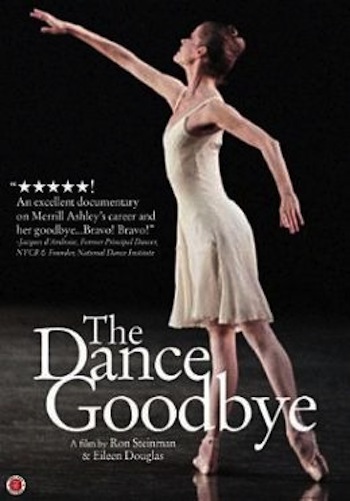

The Dance Goodbye, directed by Ron Steinman and Eileen Douglas. On DVD from First Run Features

By Debra Cash

Merrill Ashley knew that she wanted to be able to fly by the time she was five years old. The little girl from Minnesota followed her older sister into a ballet class where the students were asked to jump over a pile of coats on the floor and imagine they were leaves blowing in the wind.

The lift, the imaginative transformation, the drive. It was all there in potentia, and when she grew up, Merrill Ashley became one of the most accomplished ballerinas of her generation.

And then, in November of 1997, she had to stop dancing.

What happens when someone performs at the highest possible level of an art form and then has to give it up? It’s a question that elite athletes face — and don’t doubt that world class dancers, the artists that Martha Graham called “acrobats of God” are invariably elite athletes. But unlike, say, a major league baseball player, a professional ballerina can’t retire on a million dollar salary that has been tucked away. And unlike almost any other American retiree, when Ashley retired she was 46.

That’s the question at the heart of a sweet new documentary, The Dance Goodbye. More tribute than investigation, it pays homage to Ashley’s gifts as a performer, “muse,” and eventually, coach and teacher. With archival footage, talking heads (her fond dancing colleagues, husband Kibbe Fitzpatrick who seems like a great guy, admiring dance critics, and career transition experts), and both happy reminiscences and edge-of-tears admissions, the filmmakers distill a great dancer’s career. In the sequences taped over more than a decade, Ashley struggles with an identity crisis and the question of whether she will ever find anything that stimulates the same drive and passion she enjoyed as a performer, and what, ultimately, she wants to do in her second act.

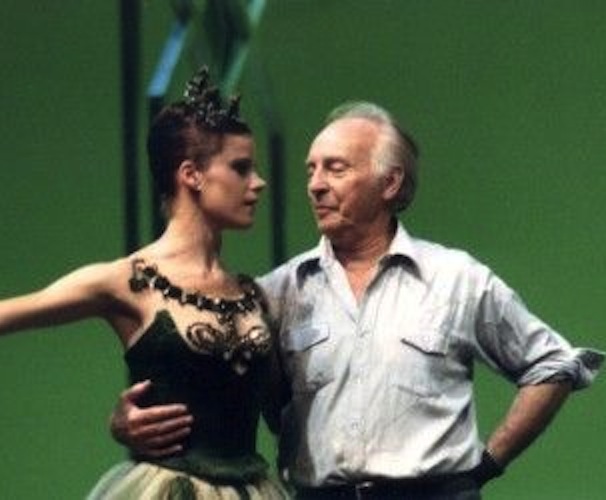

Thirteen year old Ashley moved to New York with her parents’ blessing in 1964. She had won a coveted scholarship to attend the School of American Ballet, which she describes as “a place to work, not a place to look pretty.” She never really left, rising from Nutcracker Candy Cane girl to the New York City Ballet prima ballerina whose breathtaking precision was incarnated in choreographer George Balanchine’s 1978 Ballo della Regina. Ashley’s great roles are sampled alongside her inventory of injuries and trips to the chiropractor, surgeon, and physical therapist. One of the most compelling and generalizable aspects of the documentary is the discussion of how her great absorption in what she loved to do mitigated physical pain.

Merrill Ashley and George Balanchine — she still sees the choreographer in her dreams.

At the close of her career, Ashley investigated her opportunities and came to realize that one of her favorite parts of dancing had been the process of acquiring skills. That sensibility eased her into the work of coaching and teaching. She began travelling the world staging Balanchine ballets (New England audiences will enjoy the glimpses of her coaching Lorna Feijoo in Havana before Feijoo was hired to dance at Boston Ballet). She made some sojourns into character roles, although despite what she says in the film about drawing on her frustration to create an authentic characterization of Madge the witch in La Sylphide, a guest role she performed with Boston Ballet in 2005, the performance I saw live was anything but convincing. Balanchine dancers, by and large, never learn to mime.

Hers is not a story many dancers could ever hope to replicate. When Lincoln Kirstein (of the Filene’s fortune) and Balanchine established the School of American Ballet and New York City Ballet, they did so on the model of the comprehensive, well-funded imperial institutions Balanchine had left behind in St. Petersburg. The arts in America enjoy very few places where someone can proceed from her teen years to seniority, taking different responsibilities as her skills shift. Ashley had to adjust her identity, and I respect the work it took to step away from the footlights, but she was embraced in very, very familiar surroundings. I know former professional dancers across a number of genres who have become software developers, investment analysts, physicians, and even one chauffeur. We haven’t heard enough of those stories nor publicized how the discipline and creativity of a dance background plays out in other, nonarts activities.

By the closing credits of The Dance Goodbye, you can’t help but wish Merrill Ashley well. At night, she still sees Balanchine in her dreams.

c 2015 Debra Cash

Debra Cash, a founding contributor to the Arts Fuse, is Executive Director of Boston Dance Alliance and scholar in residence at the Bates Dance Festival.

Tagged: documentary, Eileen Douglas, George Balanchine, Merrill Ashley, Ron Steinman