Visual Arts Review: “Artist Textiles — Picasso to Warhol” When Cloth Became Art

The fascinating exhibition Artist Textiles: Picasso to Warhol traces the history of 20th century art in textiles.

Artist Textiles: Picasso to Warhol at the American Textile History Museum, Lowell, MA, through March 29.

Spring Rain, a fabric print by Salvador Dali. Photo courtesy of the American Textile History Museum.

By Kathleen C. Stone

Here’s the bridge-building idea: recognized artists create textiles for the masses. It’s a melding of fine art and applied art, a way for artists to bolster their own fortunes as well as those of textile manufacturers. The approach took hold early in the twentieth century and peaked after World War II when Britain’s textile industry championed it as a way to spark production. Big names jumped in – Braque, Calder, Dali, Dufy, Léger, Matisse, Miró, Moore, Picasso, Steinberg, Warhol – and their combined efforts raised textile design to an artistic level not seen before or since.

Artists seriously undertook textile design in the early part of the twentieth century. They were inspired by Bloomsbury craftsmen who, under the influence of William Morris and the English Arts and Craft movement, designed fabrics as a means to make art less elite. When French painter Raoul Dufy applied Fauvist colors and fanciful figures to textiles, the movement gained European panache. British textile producers attempted to keep up the momentum, but two World Wars thwarted their efforts. It was not until the late 1940s that conditions once again became favorable for a large scale marriage of art and textiles. At that point a consortium made up of the British government, textile manufacturers, and design professionals pooled their efforts; a 1946 show at the Victoria and Albert Museum, Britain Can Make It, showcased British products of all sorts, including textiles. Ironically, visitors to the museum could look at but not buy the featured designs. British wartime austerity measures were still in place, so manufacturers were aiming for overseas markets, particularly in America.

Artists such as Patrick Heron, Henry Moore, Eduardo Paolozzi, and Nigel Henderson were involved early on. Some of them, particularly Paolozzi and Henderson working through their Hammer Prints studio, elevated textile making to an impressive new level. For example, they employed the cubist approach of reproducing a Parisian newspaper in one of their screen prints. In a piece of bark cloth they created an intricate arrangement of geometric shapes and images of everyday objects, such as the rounded forms of bicycle tires, eyeglasses, and pocket watches.

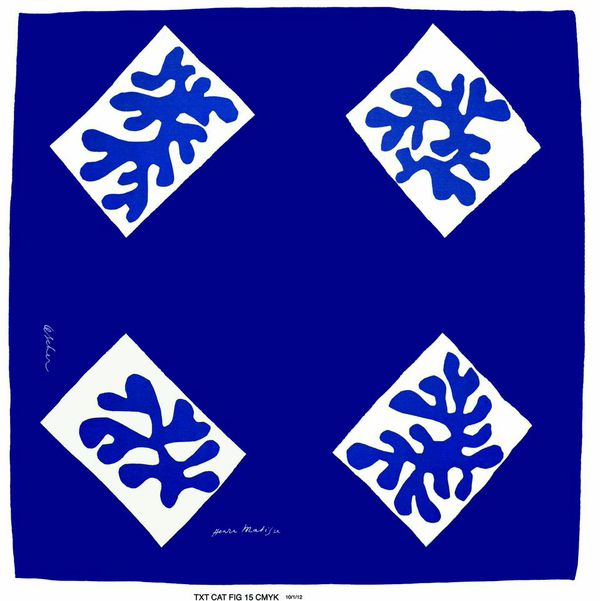

Soon international artists saw textile design as a respectable, and potentially lucrative, endeavor. French painter Georges Braque created a distinctive “still life” series for a cotton rayon blend. (Made from wood pulp cellulose, rayon became commercially viable in the 1950s through the efforts of British researchers.) The Italian sculptor Marino Marini wove a horse figure into a silk jacquard fabric. Henri Matisse rendered his signature multi-footed abstract figures in blue-and-white silk, while Alexander Calder transported likenesses of carefully balanced figures from his mobiles onto a scarf.

A scarf designed by Henri Matisse. Photo courtesy of the American Textile History Museum.

The Horrockses company, a British dressmaker of long standing, crafted cotton dresses for Queen Elizabeth to wear for her 1953 coronation tour of the Commonwealth. Many of these fabrics are floral prints by British artists that, when styled into a dress with, say, a flared skirt and a flat collar, produce a matronly look. Undoubtedly it was a deliberate choice; this is how the new queen wanted to be perceived by her subjects. In some other of the show’s pieces the style fails the fabric. One example is a tightly pleated skirt where the profusion of pleats obscures the design. But some of the clothing in the show is highly successful. One of my favorites is a yellow and black strapless dress, vintage 1953, made by Horrockses of Paolozzi fabric.

Eventually, American textile producers realized that artist-designed textiles were commercially viable, and by the late 1940s were cultivating their own stables of artists. Early on, Wesley Simpson engaged Hungarian Marcel Vertes and Spaniard Salvador Dalí as designers. The latter softened his surrealist approach to produce fabrics that are striking, beautiful, and only a little witty. In the 1950s, Fuller Fabrics enlisted Marc Chagall, Raoul Dufy, Fernand Léger, Joán Miró, and Pablo Picasso for its Modern Masters series. Fuller’s concept was to use recognizable images as inspirations for its designs: artists would reproduce a known painting and the company would manufacture the fabric using the economical roller printing method. The material was sold, inexpensively, by the yard. One in the series, Dufy’s Le Maronniers, shows repeating lines of chestnut trees interspersed with mansard-roofed apartment buildings and men seated in park chairs reading the newspaper. The scene looks as though Maurice Chevalier might stroll by at any moment. Miró’s fabrics are vibrant and colorful, typical of his paintings. Picasso worked with Fuller and other American producers as well. A design of his was used for one of my favorite pieces in the show — white fawns prancing on a black background. The cloth of fine-wale corduroy is styled into ankle-length culottes for a hostess to wear serving cocktails.

Even Saul Steinberg’s sense of humor made its way into fabric. Line drawings inspired by his cartoons and covers for the New Yorker — images of cowboys, a wedding couple, a stick-up artist, circus performers, and steam trains — made their way into fabrics sold at J. C. Penney. You could see this form of “branding” as a precursor to the Martha Stewart products the store sells today — but it is quite a stretch.

Two dresses made of fabric designed by Andy Warhol. Photo courtesy of the American Textile History Museum.

Not to be left out of the fun, Andy Warhol took up fabric design in the 1960s. As he did in his other work, he seizes images of a common object, such as a button or an ice cream cone, and repeats them in various colors and positions. And true to form, he appropriates images from the work of others: a pocket watch in one of his fabrics replicates the pocket watch in the Paolozzi and Henderson bark cloth, even down to the hands being positioned at 11:40 o’clock.

This is a fascinating show, if only because it’s exciting to see so much beautiful work in one place. The exhibition captures a rare historical period when, on both sides of the Atlantic, the practical arts and fine art came together. Now that textiles are being mostly manufactured in Asia, that kind of symbiosis will not come again, at least not in the same way.

I do have one quibble, though. The show’s title does not do it justice. Most likely someone in London, where the exhibition originated (it had a successful run in the Netherlands and will move on to Toronto after it leaves Lowell), decided to highlight the names of Picasso and Warhol, figuring that it would attract visitors, and that may well be true. But the art on display here is much deeper and richer than the work by these two artists alone. I lingered at Artist Textiles: Picasso to Warhol, discovering British artists who were new to me, and appreciating pieces made by familiar artists in a new medium. And I had an exhilarating glimpse into a moment when delight in a new form of art united artists, manufacturers, and consumers.

Kathleen C. Stone is a writer pursuing her MFA degree, a lawyer who earned her JD many years ago, and, even before that, was a student of art history. Her blog can be found here.

Tagged: American Textile History Museum, Artist Textiles: Picasso to Warhol