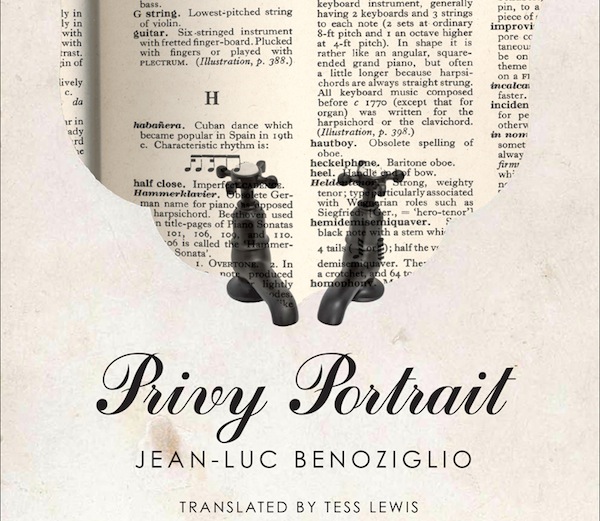

Book Review: The Darkly Droll, Desperately Farcical “Privy Portrait”

Privy Portrait portrays a contemporary human being who has lost all handholds, all footholds, all practical, moral, and metaphysical support — except for that provided by the articles of his beloved encyclopedia.

Privy Portrait by Jean-Luc Benoziglio. Translated by Tess Lewis. Seagull, 256 pp., $24 (cloth).

By John Taylor

For ten days, I was so thoroughly absorbed in Jean-Luc Benoziglio’s Privy Portrait that I remained torn between devoting an afternoon to finishing the darkly droll novel and continuing to read it in snatches in order to prolong the particular emotion it provoked. Every day, I chose the latter solution, all the while wondering how I had managed to overlook Cabinet portrait—the original title — when it appeared in French in 1980 and won the Médicis Prize. Tess Lewis has provided an invigorating translation that captures the amusingly colliding layers of diction in the French prose.

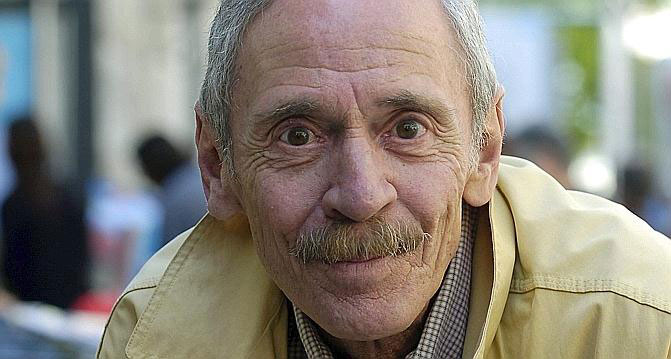

In a plot that artfully flits between past and present, Benoziglio (1941-2013) combines joyfully bleak introspection, lively dialogues (or shouting matches), troubling nightmares, absurd or sordid mini-events, oblique yet telling flashbacks, funny asides about writing, and inserted passages taken from the encyclopedia volumes perused by the narrator in the common toilet used by him and other tenants in a Parisian apartment building.

The novel begins with the narrator’s move into a tiny room in that run-down building. He is now estranged from his wife Stérile and young daughter Stéphanie, is blind in one eye, and suspects that he has rectum cancer because of violent pains that assail him.

The concierge assures him that he will eventually get used to the behavior of the other tenants on his floor. It is a real “circus” — a recurrent word. There are gruesome groans behind a door. One neighbor is a somewhat alluring single mother with a mentally retarded, psychologically disturbed son whose behavior can be worrisome. Above all, the narrator must live alongside the Sbritzkys, a vociferous couple who keep their television blaring all day long and who lord over every single detail of the other tenants’ daily life.

Besides their overall vulgarity and aggressiveness, the Sbritzkys are anti-Semitic, whereas the narrator has reached a point in his life when he must come to terms with his Jewish heritage. He has little information about his paternal ancestors, most of whom perished in the Shoah. He knows that his father, chillingly designated throughout the novel as “the man in the white coat” (for he was a psychiatrist), was a descendent of Sephardic Jews who had settled in Turkey after the expulsion of the Jews, in 1492, from the Spain of Ferdinand and Isabella; and he is aware that his father had emigrated to Switzerland for his medical studies two years before the outbreak of the Second World War. Settling in the country at the time, he escaped the Holocaust. Passages reveal the extent to which the father-son relationship remained remote—to say the least—during the narrator’s childhood.

In its broad outline, Benoziglio’s own life parallels that of his narrator: the Francophone writer was also born in Switzerland, of a Turkish father and an Italian mother, and he moved to France in 1967. In the novel, the narrator harbors no special attachment to, nor repulsion for, his native country. He has also lived in France for several years, an expatriation by no means implying that he has become “French.” Essentially without a country, he has other doubts about his personal identity as well.

This Wandering Jew theme, which is introduced discreetly into the novel and grows in intensity, is especially compelling. Ever with clownish humor not without twists of poignancy, Benoziglio describes a man who has lost his stability in the world. This is not only due to the break up of his immediate family or to the loss of his job, but also to this unsettling family history, on his father’s side, which is enveloped by a “ghostly and glacial fog.”

Although the narrator mocks his own feelings of existential insecurity, they eat away at him. This angst becomes increasingly clear in a novel that occasionally discloses disturbing and haunting elements within an otherwise farcical — desperately farcical — atmosphere. Beneath the narrator’s playful cynicism lies a sort of yearning. Signs of his sensitivity to his incurable rootlessness include his imaginary conversations with a “cousin” in Turkey and his attempts to catch bits of news about the country by listening to the television broadcasts roaring out from the Sbritzkys’s apartment.

“According to my neighbors’ television set,” he notes for example, “things don’t look good in my cousin’s country. It’s so bad, in fact, that if I took up arms and went I wouldn’t know whom to shoot.” And he muses, now and then, about the few surviving family items that offer clues to his vague, lacunary, Turkish-Sephardic background.

Author Jean-Luc Benoziglio — with clownish humor and twists of poignancy, he describes a man who has lost his stability in the world.

However, as a key flashback reveals, the narrator actually feels only part Jewish, if Jewish at all. Recalling a time when he “was earning money by the shovelful” at the “Bank of Thingy & Co,” he remembers a conversation with a Jewish colleague. The colleague was baiting him, in a bar, to acknowledge his religious heritage:

“For God’s sake,” I whispered furiously enough to strike water from a stone, “try to understand that I’m not interested in the religious side of the issue. I don’t give a shit about religion. Besides, for all I know, my ancestor back there could well have been a communist or a freemason or an atheist or an Islamic convert or a sun worshipper, what difference does it make? Does it change anything?”

“Precisely,” he said. “It doesn’t change a thing. Whether you like it or not he was and he remained a Jew. Like you.”

“Only part,” I said.

“Now really,” he began, “why do you always have to renounce, play down. . . What do you mean by ‘only part’?”

“What I mean is, my mother isn’t one.”

He choked on his drink.

“Your mother’s not Jewish?”

“Nope.”

“But then,” he spluttered, “if your mother isn’t, then you. . . Then you, sir, are not one of us at all? Do you know what Solomon said?”

I wasn’t even sure who Solomon was. …

Beyond the particularities of the Jewish existential condition, which are conjured up with wit and subtlety, Privy Portrait portrays a contemporary human being who has lost all handholds, all footholds, all practical, moral, and metaphysical support—except for that provided by the articles of his beloved encyclopedia. The recorded knowledge of the world provides a last mainstay, a final refuge: he locks himself in the privy for hours until the thunderous knocks of the Sbritzkys or some other tenant draw him out.

But even the encyclopedia might well disappear. The Sbritzkys sabotage the volumes in grievous ways and pressure the narrator to remove them. There are no redeeming characters in the novel except, perhaps, the hapless retarded boy to whom the narrator is kind on a couple of occasions. Even Asparagus and Brick House, the two more or less friendly movers, eventually cheat him out of some money through their “Second to Last” drinking game. Can writing somehow save him? It is the narrator who is writing this deep-probing, grotesquely entertaining novel.

John Taylor, originally from Des Moines, has lived in France since 1977. He is the author of the three-volume Paths to Contemporary French Literature (2004, 2007, 2011) and Into the Heart of European Poetry (2008). A new collection of essays, A Little Tour through European Poetry, will be published next month by Transaction. His most recent collection of personal writings is If Night is Falling (Bitter Oleander Press, 2012). He has translated several French poets, including Philippe Jaccottet, Jacques Dupin, Pierre-Albert Jourdan, Louis Calaferte, and José-Flore Tappy.