Theater Review: A Superbly Gritty Staging of August Wilson’s “Fences”

Director Eric C. Engel and the Gloucester Stage Company cast gives Fences an insightful and nuanced production.

Fences, by August Wilson. Directed by Eric C. Engel. Staged by Gloucester Stage Company, at the Gorton Theatre, 267 East Main Street, Gloucester, MA, through September 7.

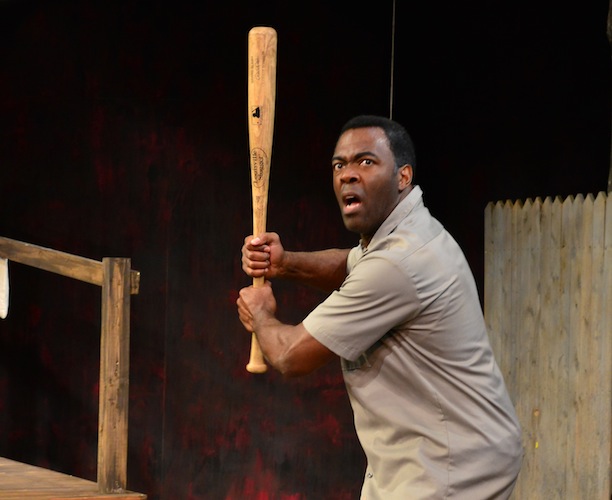

Daver Morrison as Troy Maxson in a scene from the Gloucester Stage Company production of “Fences” Photo: Gary Ng.

By Robert Israel

If he were alive today, African-American playwright August Wilson (1945-2005) would probably have grimaced if he learned that Eric C. Engel, a white director, was at the helm of the Gloucester Stage Company’s production of Fences. Yet Engel gives Fences an insightful and nuanced production. So a few words of perspective on Wilson follow.

In 1976, I met Wilson at Penumbra, an African-American troupe, in St. Paul, Minnesota. He had not yet embarked on playwriting, but during our chat it was obvious that it wouldn’t take him long to discover his métier. He possessed a fierce intelligence, deeply set, glowing eyes, and an arresting brilliance fueled by anger and raw talent.

Almost a decade later, Wilson and I chatted again at Yale Rep in New Haven, Connecticut during the pre-Broadway tryout of Fences, which starred James Earl Jones. Wilson said he had only a vague recollection of meeting me, though otherwise he displayed an eidetic memory: standing on a busy downtown New Haven street corner, he recited lines of the play we saw in St. Paul, spoken by not one, but several of the characters.

Wilson’s fierce wellspring of anger was rooted in attacks of racial prejudice he had personally endured as a young man, hostility that forced him to leave his native Pittsburgh – where Fences is set — before his high school graduation. In the ensuing years he learned to tap into that rage through art, penning plays that chronicled the epic expanse of the African-American experience, from the time of blacks’ forced arrival in the United States as slaves and beyond – one decade at a time – throughout the twentieth century.

Fences was awarded the Pulitzer Prize in 1987. Anger blazes in almost every scene. And that ferocity explains why Wilson would have objected to the Gloucester Stage production: he insisted that only African-Americans direct his plays. His rationale: black directors understood his work the best. Also, by fighting to give African-American directors opportunities to direct, they would excel, as he did, in a field dominated by white men and women. In 2009, a media conflagration erupted when a white director was chosen for a production of Joe Turner’s Come and Gone, prompting a noted black director to accuse Lincoln Center in New York of committing “institutional racism.”

Regardless of this controversy, Engel has done Wilson’s difficult script proud, thanks to a gifted, all-black cast, who collectively deliver the grit, the poetry, and subtleties of Wilson’s characters.

The plot revolves around Troy Maxson (Daver Morrison), a Pittsburgh sanitation worker in his early fifties who has led a rough and tumble life. Through a series of interwoven stories, we learn that Maxson has migrated north to Pittsburgh, sired a son, Lyons (Warren Jackson), from a previous marriage and another son, Cory (Jared Michael Brown,) from his present union with Rose (Jacqui Parker). He has served time in the penitentiary where he met his friend, Bono (Gregory Maslow). It is 1957, and relations between whites and blacks are abysmal.

Wilson’s distinctive gifts as a playwright are rooted in his use of characters are storytellers. His figure’s tales are not only interesting in and of themselves, but they serve as complex dramatic devices that reveal — consciously and unconsciously — the speaker’s conflicts and blind spots. Troy’s circumlocutionary way of spinning his stories is theatrically compelling, but also revelatory of his psychological weaknesses. At one point, he tells a heroic yarn that goes off on tangents, mixing in scenes from the Bible, his past, a meeting with Death, the Devil, his past and current dreams, his failures, and his brief moments of triumph. Morrison skillfully blends these fragments of desire, frustration, and fantasy together, melding the protagonist’s harsh side with his obvious sensitivity. In his portrayal of Troy, Morrison suggests, early on, the character’s randy sexuality, the root of the contradictions that become pivotal in the play’s second act. James Earl Jones, who acted the role of Troy on Broadway, towered over the other members of the cast, casting them into the shadows. Morrison’s performance is more subtle and thus more inclusive — he blends in with the ensemble.

The cast performs admirably. Parker is particularly wonderful as Troy’s long-suffering wife Rose; she brings an admirable restraint to the role. Still, Fences is a weighty play, and the performers sometimes buckle under that weight. There are several moments in the production when they deliver their lines without sufficient punch or sass or their placement on the stage is awkward. (Perhaps the occasional clumsiness is due to Gloucester Stage’s demanding and accelerated rehearsal time. By the time the production moves to the latter part of its run, the cast will most likely be firmly in Wilson’s groove.)

I was particularly impressed by Jermel Nakia in the role of Gabriel, Troy’s war-damaged brother. The performer’s frantic pacing on stage, his twisted limbs and scuffing feet, are mesmerizing to watch. He seems to be channeling his character’s madness, making his anguish palpable. I only wished the last scene, in which Gabriel blows upon a broken trumpet, was staged with the same attention to nuance that is found throughout the rest of the production. This is a pivotal moment, when Gabriel’s insanity brings forth a celestial blessing. The timing of Russ Swift’s lighting was off, so the scene misses its forceful mark.

Given the unrest that is still smoldering in Ferguson, Missouri, Wilson’s perspectives on America’s racial tragedy are needed now more than ever, as we continue to grapple, as a nation, with how to ensure dignity, freedom, and human rights for all our citizens.

Robert Israel writes about theater, travel and the arts, and is a member of Independent Reviewers of New England (IRNE). He can be reached at risrael_97@yahoo.com