Book Review: “The Marrying of Chani Kaufman” — The World of the Ultra-Orthodox Jews, Treated With Verve and Empathy

Beneath the humor and the warmth and the charm of this novel, author Eve Harris bears witness to an existence far more complex and troubled than Ultra-Orthodox Jews might like to admit.

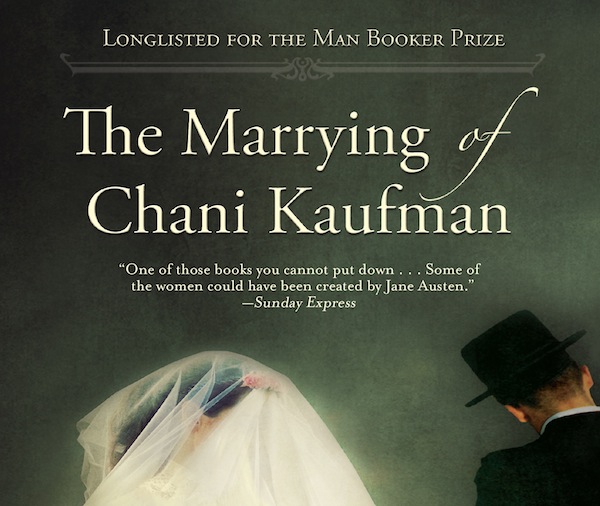

The Marrying of Chani Kaufman by Eve Harris. Black Cat Paperback, 363 pages, $16.

By Roberta Silman

This is a delicious, very readable debut novel which was published in England last fall, longlisted for the Man Booker Prize, and delves into the closed world of the Ultra-Orthodox Jews, the Charedi, living in London in 2008. Born of Israeli-Polish parents in London, Harris apparently drew on her experience as a teacher in a Charedi school for her material, and it is a testament to her compassion that, although she is not “of them,” she understands that world as thoroughly as Jane Austen understood hers. Moreover, although this is a world easily mocked, Harris has too much sympathy and respect for her characters ever to stoop to that.

Marriage in the Charedi world is always a circuitous affair, thus the sly title of this book, The Marrying. And although the frame for the book is the actual marriage of Chani to Baruch Levy, starting with Chani waiting in her bride’s dress in the “Bedeken” room (where the groom verifies that she is the right girl) and ending with a somewhat disastrous, yet hopeful wedding night, Harris gives us all the details that lead up to the big event. Details that are sometimes hilarious, sometimes sad, often unbelievable, yet always interesting. Her assured voice provides the necessary information, enhanced by a glossary at the end of the book which gives us the meanings of the Yiddish in the text.

Unlike most Charedi couples whose marriages are arranged, twenty-year-old Baruch Levy has “sighted” Chani Kaufman and is attracted to the lovely, lithe nineteen-year old. When he requests that his mother ask the community’s matchmaker, the cunning Mrs. Gelbmann, to find out more about her, the tale unfolds. And, as we might expect, Chani, who is from a poor family of seven girls and whose father is a “nobody” rabbi of a small shtiebel (more a study house than an official synagogue) in Hendon, does not fulfill in any way the hopes of Baruch’s family. Mr. Levy makes his living in real estate, they live in more affluent Golders Green and Mrs. Levy gives new meaning to the word, snob. Her exchanges with Mrs. Gelbmann are priceless, and their dance around class and money among the best scenes in the book.

Moreover, although the Kaufmans are from learned lineage in Vilna and Kiev, Chani has been a little too “lively” to take the usual route. Instead of going to the Seminary where Charedi girls are taught all their obligations, she has chosen to become an assistant teacher of art at her high school, aptly named “Queen Esther.” How Chani and Baruch are eventually allowed to meet and grow to like each other, then handle the obstacles to their union is one thread in the book, the one where Harris shows her wit and warmth and sense of fun. Here is Chani thinking about what has happened to her:

In her world, people did not fall in love. They were chaperoned into marriage. They met, they married and then they had children. And somewhere along the line; they got to know each other. They became a team, husband and wife, bringing more babies into the world, as HaShem [God; literally, the name] willed it. And if they were fortunate, HaShem smiled upon them and gradually they learned to love each other. . . .Falling in love was for the goyim.

But there is also a darker thread — the story of the Zilbermans, the Rabbi Chaim and his Rebbetzin, Rebecca, and their son Avromi. As the Rebbetzin helps Chani prepare for her wedding, taking her to the Mikveh and advising her, Harris weaves their story into the skein of this novel almost as a cautionary tale: What sometimes happens to love within the confines of Charedi life. We learn how the Zilbermans met as young “secular” Jews in Jerusalem in the early 1980’s — she from England, he from South Africa — how they fell in love, first with each other, then with ultra-Orthodox Judaism. An idyllic existence until tragedy strikes and they come to London, where they have three sons, one of whom seems to have inherited the secular gene.

We participate in the Rebbetzin’s joy when she discovers she is pregnant (late in life, thus, a miracle) with, she hopes, the daughter she always wanted, then her sorrow when she loses the baby and faces how arid and depressing her life with Chaim has become. Here she, who has become Rivka instead of Becca, is thinking about her marriage:

Everything slowly became rigid and conservative, including her husband. He threw out all their old pop records, replacing Elvis Costello and The Jam with the sound of famous cantors singing psalms and liturgy.

She took to wearing dark, wintry, neutral shades that made her feel old and frumpy. Her brilliant headscarves. . . were exchanged for mop-like sheitels [wigs]. She put away her bangles. . . and wore only her wedding ring. On the outside, she became the model rabbi’s wife, a paragon of virtue, modesty and kindness. She visited the sick, she attended Rosh Chodesh meetings, she prayed and baked and cleaned and welcomed and brought up her children in the approved Yiddisher way. She smiled even though her cheeks ached from the effort.

Rivka is also worried about her eldest, Avromi, Baruch Levy’s good friend, and is not really surprised when she discovers he has been having an affair with Shola, who is half-Nigerian and is absolutely clueless about the cost of her and Avromi’s actions.

Skillfully, Harris moves back and forth in time and into the heads of several narrators to tell her story; for the most part the pieces come together in a meaningful, coherent way (my only cavil is that she reveals the Zilbermans’ tragedy too late in the book). Yet underlying all those shifts she never loses sight of her abiding theme — Charedi culture’s utter lack of communication. Its participants are so busy following strict rules about food, clothes, reproduction and parenting that the important things are never faced or discussed. Here is Chani and her mother talking about sex:

‘You’re frightened, my darling, aren’t you?’ said Mrs. Kaufman.

‘No, not exactly — well, yes, mum.’

‘Well . . . I guess every Kallah [bride] has to do what she’s got to do. All your sisters seemed to manage perfectly well . . .’ pondered Mrs. Kaufman.

‘Mum! That’s not helping!’ She could brook her frustration no longer.

‘I know, darling, but it’s been so long since I was a bride . . . I’m trying to remember what I felt like . . . your father was very good to me that night . . . I think the important thing to remember is that there can only be one first time for every woman. And to get on with it — let your husband do his duty. Don’t stop him. And you must do yours . . . the less fuss, the better . . . and may Ha Kodesh Ha Borech Hoo bless you with a child — He has already blessed you with a hossen [bridegroom], hasn’t He? A boy from a good Hasiddisher family, the right sort — and he’s a yeshiva bocher [a talented yeshiva scholar]. I am sure it will be fine.’

‘Amen. But did it hurt?’

‘Did it hurt? Hmmm . . . eight children later — Chani, I can’t honestly remember! If it did, it’s a fleeting pain . . . it won’t last and it will get better with time and practice my darling, you’ll see.’

‘That’s exactly what the Rebbetzin said –’ sighed Chani.

Amusing, but not much help to these kids — for they are no more than kids — who want to know a lot more, including how to not have babies so quickly and/or so rapidly after the first one. So although Chani and Baruch seem able to triumph over their ignorance at the end of the novel, ignorance that has brought humiliation upon them both, I found myself wondering about the less lively, the less savvy Charedi kids and where their blinkered life will lead them. About the cruelty implicit in the Charedi life where such things as sexual pleasure and equality between the sexes and acknowledgment of past tragedies — to name only a few such examples — are denied with such fervor. For beneath the humor and the warmth and the charm of this novel, is Eve Harris’s need to bear witness to an existence far more complex and troubled than its followers might like to admit. That she has done so with such verve and empathy is cause for celebration.

Roberta Silman is the author of a story collection, Blood Relations, now available as an ebook, three novels, Boundaries, The Dream Dredger, and Beginning the World Again, and a children’s book, Somebody Else’s Child. A recipient of Guggenheim and National Endowment for the Arts Fellowships, she has published reviews in The New York Times and The Boston Globe, and writes regularly for Arts Fuse. She can be reached at rsilman@verizon.net.