Peter Walsh

Yun Ko-eun’s novel is a good, entertaining read that proceeds by a kind of literary Zeno’s Paradox: forever on the verge of some Big Revelation or vague Deeper Meaning without ever actually reaching them.

Lynda Nead’s meticulous, competent, and impressively researched approach gives the work weight without making it ponderous; “British Blonde” seems destined to serve as a text for classes in gender or cultural studies.

Olivia Laing’s hard-driven narrative, set mostly in 1975, combines a gay romance with a literary text about the dangers of resurfacing fascism, a discourse on 20th-century avant-garde film-making, and a political thriller.

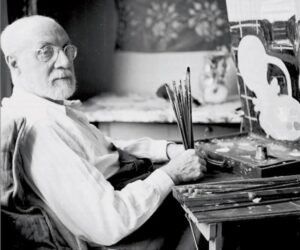

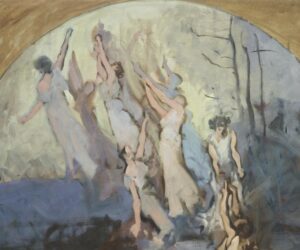

All in all, this is a crisp, entertaining, and, so far as I can see, an accurate account of the last acts in Henri Matisse’s career.

“Matisse in Morocco” is a 35-year labor of love, as meticulously researched as a Ph.D. thesis but without the turgid language, as charmingly composed as the travelogues of Goethe, and with characters worthy of Balzac.

Every subject in Jim Dine’s richly rendered work seems to edge towards something other than itself, deeper and more personal.

The stunning painting is beautifully presented in this documentary, but the flood of references to other works of art and quotations from classical and Renaissance writers might make the film a bit slow going for someone with no background at all in Renaissance cultural history.

The symbolism here can grate loudly against reality. Those panels extolling the creativity and stoic virtues of the American working class clash with the ways workers were actually treated during the Gilded Age.

Yes, Munch and Kirchner were into angst; but they were also artists of great energy, talent, and daring, who found new ways of working and did much to shape the direction and force of modern art.

Anka Muhlstein’s book is probably best read as a biography of a hard-working family man and not as a thorough assessment of Pissarro’s art.

Design Review: The Look of the 2026 Milano Cortina Winter Olympic Games