Book Review: “Camille Pissarro: The Audacity of Impressionism” — A Man of Admirable Qualities

By Peter Walsh

Anka Muhlstein’s book is probably best read as a biography of a hard-working family man and not as a thorough assessment of Pissarro’s art.

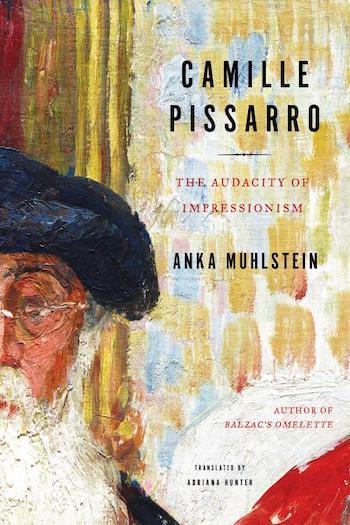

Camille Pissarro: The Audacity of Impressionism by Anka Muhlstein. Translated by Adriana Hunter. Other Press, 320 pages, $29.99.

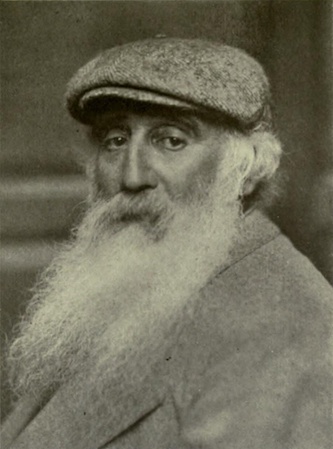

I can think of several things that make the artist Camille Pissarro an ideal subject for a biography. He lived and worked at the center of the most influential movement in modern art: he has been called, a bit misleadingly, the “Father of Impressionism.” Born in 1830, in the capital of the Caribbean island of St. Thomas in the Danish West Indies (now the U.S. Virgin Islands), Pissarro’s family background was French and, mostly non-practicing, Jewish. He was the oldest of the core Impressionist group, though not by much (Manet was just eighteen months younger), and wore a long white, patriarchal beard. But his role might better be described as “Elder Statesman,” holding together as a movement a diverse, ambitious, and cantankerous group of artists united by little more than their relationship to him. Or as the group’s “Senior Philosopher,” the one who tried hardest to articulate an aesthetic of radical painting and to describe the (mostly illusive) principles that held the group together.

Pissarro knew most of the people who really mattered in French art, from the start of the Third Republic to his death in 1903. He taught and mentored two of the most important artists of the next generation — Cezanne and Gauguin — who in turn exerted an enormous influence on the several generations that came after them. You could say his influence — as it warped and developed its way through modern art — has never ended.

Pissarro was also a prolific and articulate letter writer. His wide range of correspondents included family members, especially his eight children who survived childhood, his fellow impressionists and other artists, art dealers and critics, political and literary figures of the day. Along with Van Gogh’s letters, Pissarro’s rank with the great literary treasures of modern art: they make a delightful read, full of clear-eyed observations and a wry yet good-natured sense of humor, a passionate, well thought out engagement with contemporary issues in art and politics, and reams of sensible advice for his students and offspring. For the biographer, this material has the additional advantage of having been expertly edited and published in multiple volume sets, meaning there is no need to travel off to distant, inconvenient archives or to pester heirs of his correspondents for permission to read them.

Professional biographer Anka Muhlstein has made ample use of all this original material in her new book, Camille Pissarro: The Audacity of Impressionism. Muhlstein is the biographer of or author of studies on a wide range of political, aristocratic, and literary figures, including Queen Victoria, Baron James de Rothschild, Cavalier de La Salle, Catherine de Medici, Marie de Medici, Elizabeth I and Mary Stuart, and Balzac. Her book on Proust has been much praised and she won the Goncourt Prize for her biographer of the Marquis de Custine, best remembered as a travel writer. She has been married since 1974 to the Polish-American novelist Louis Begley and lives with him in New York City, though she continues to write in her native French. This book, Muhlstein’s first devoted to single artist, was ably translated by Adriana Hunter.

Muhlstein leans, for shape and plot, on the long-established standard Pissarro biography, Ralph E. Shikes and Paula Harper’s Pissarro: His Life and Work (1980). Unlike Shikes and Harper, though, she has not written a work of scholarship or art history. She writes for the general reader, provides no unexpected revelations, and unrolls no new theories. She discusses or illustrates relatively few works of art and her treatment of them is mostly descriptive, not analytic.

Photo of Camille Pissarro, around 1890. Photo: Wiki Common

This is not, then, a book to read to understand the complicated aesthetic battles around Impressionism and Post-Impressionism. Instead, Muhlstein focuses on the Pissarro the man. He is a man of admirable qualities — steady, sober, hard-working and a serious thinker, a dedicated father, teacher, and friend, a committed leftist, always concerned for the poor, exploited, and politically wronged. These are not qualities found together in most modern artists. Her tone is largely domestic, perhaps influenced by the letters, which often take up family concerns. Her writing style, at least in translation, is relaxed and approachable and free of fashionable jargon.

Like many who come from other fields to write about art and artists, Muhlstein makes a few art historical errors. She refers to the makers of the Japanese woodblock prints that so influenced the Impressionists as “engravers.” In fact, they were practitioners of a completely different method of print-making: this may have been a mistranslation of the French phrase gravure sur bois (literally “engraving on wood”), the French term for “woodcut.” Later on she refers to “engravings” when she clearly means the experimental etchings that Pissarro and other Impressionists produced.

More problematic are the omissions and elisions of some details that can have a significant effect on how a reader understands the Impressionist circle. She introduces Cezanne, for example, as the “son of a banker.” That is perfectly correct but it entirely misses Cezanne’s class background and its important role in the Impressionist group.

Cezanne was born into a prosperous family of peasant background in the South of France. The rich peasant — an oxymoron before the Revolution abolished the aristocracy and began to erase class distinctions — was a distinct type in 19th-century France. In literature, they are portrayed as crude, grasping, and obsessively materialistic, scheming, miserly, and manipulative people who are ready to thwart any social and familial norm in the service of making another franc. Moreover, to a city slicker Parisian, anyone from Provence was bound to be a hick.

Thus Cezanne was always an outsider wherever he was (except, perhaps, when working with the bias-free Pissarro). At home he was different because he was an artist; in Paris he was looked down on for being provincial. The rest of the Impressionists came from mostly bourgeois or even (in the case of Degas) aristocratic origins. Cezanne played out his class anxieties via such bourgeois-baiting tactics as showing up for social events in dirty, ragged workman’s clothing, exhibiting bad manners, and generally acting like the complete bumpkin. Muhlstein describes all this without explaining its psychological origins.

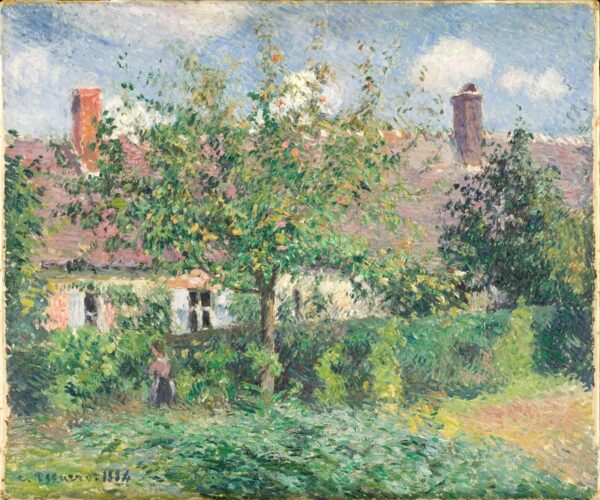

Camille Pissarro’s “Peasant House at Éragny,” 1884. Photo: Wiki Common

Cezanne was, in fact, well educated as a youth and, at his father’s request, studied law at the University of Aix-en-Provence. But the rest of the Impressionists, even Pissarro, thought that Cezanne — and his work — were pretty weird. Even Zola, a close childhood friend, considered Cezanne a dramatic failure and made him the subject of a sensational novel. After his father died, Cezanne returned to Aix and his family’s estate. While living in Aix and its environs he made his greatest works and had less and less to do with his former Paris compatriots. Near the end of his life, Cezanne turned the tables on them by exhibiting in Paris the extraordinary post-Impressionist work that had such powerful effect on a younger generation of artists that it formed a bridge to 20th-century modernism.

When Pissarro relocates his family from Paris to the cheaper town of Pontoise just north of the city, Muhlstein notes only that the place offered many suitable subjects for his paintings. In fact, he had entered the strange, ambiguous landscape of the lower Seine and its tributaries, land that became “Impressionist Country” in the same way that the Stour Valley became “Constable Country.” Pontoise, Argenteuil, Eragny, Giverny, and other Parisian railroad exurbs where the Impressionists often lived and worked were neither exactly country or suburbs, neither entirely pastoral or industrial. Railroads made these areas possible and popular: riverside and river island resorts in the area attracted lower middle class revelers from Paris, noted for their often rather lewd antics. These, too, became the subjects of many now-famous Impressionist canvasses.

Though many of these towns had had long and rich histories, most of the physical evidence had long since been swept away by wars, revolutions, and the grindstone of time. Even as the Impressionists painted them, they were subject to such urban intrusions as railroads and factories. Industrial development eventually swept away the asparagus fields and riverside gardens and villas of Argenteuil, for example, leaving it unrecognizable. It was an erratically changing, richly undetermined land; its transformations reflected the vast social, economic, and environmental changes in French society during the Third Republic. Many of the most famous Impressionist images were painted against this distinctly modern backdrop, which lent a social tone to their work that Muhlstein largely ignores.

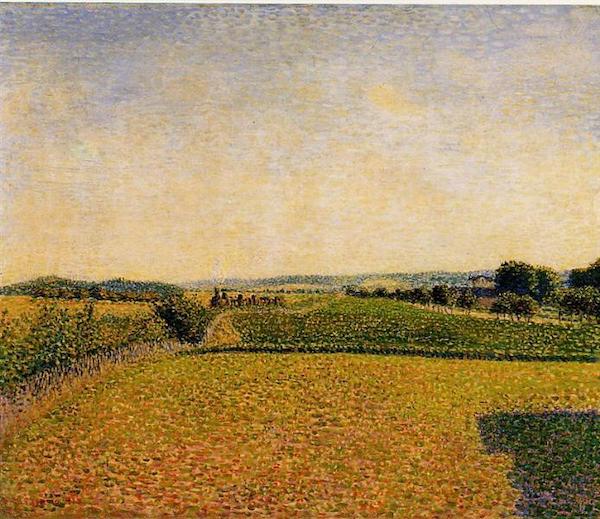

Camille Pissarro, “Railroad to Dieppe,” 1886. Photo: Wiki Common

Most puzzling of all to serious students of Impressionism might be Muhlstein’s omission of any mention of the late 20th-century, revisionist scholarship generated by Impressionism specialists like T.J. Clark, Paul Hayes Tucker, and Albert Boime. This generation refocused the idea of Impressionism: an earlier, mostly formal approach that thought of the group primarily as stylistic innovators, capturing fleeting effects of light with dabs of “broken color” gave way to a vision of them as astute observers and recorders of French society as it adapted, often badly, to modern life.

Since Muhlstein makes no mention of this later approach, it is impossible to know whether she rejects it entirely or is simply unaware of it (which seems unlikely). She does seem to go out of her way to reject the notion that Impressionism had any social or political dimension. She claims, for example, that when an Impressionist painted a locomotive, it just happened to be there. The engine wasn’t a political symbol. Of course, a speeding locomotive does not pause to have its portrait painted; including it in a finished painting could only be a deliberate choice. Throughout the 19th century, in both North America and Europe, locomotives, railroad bridges, and train stations were repeatedly used as symbols of uncontrollable technical progress and power. These were industrial intrusions on unspoiled countryside.

Although Muhlstein accurately describes Pissarro’s own deep commitment to radical leftist ideology, she argues that it did not affect his art and that Pissarro himself claims his work was not political (what he actually said was that he believed his painting was in harmony with his political views but couldn’t explain exactly how). She reverts to early periods of scholarship without considering later alternatives, even if only to reject them. For this reason, her book is probably best read as a biography of a hard-working family man and not as a thorough assessment of Pissarro’s art.

Peter Walsh has worked as a staff member or consultant to such museums as the Harvard Art Museums, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, the Davis Museum at Wellesley College, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, the National Gallery of Art, and the Boston Athenaeum. He has published in American and European newspapers, journals, and in scholarly anthologies and has lectured at MIT, in New York, Milan, London, Los Angeles and many other venues. In recent years, he began a career as an actor and has since worked on more than 100 projects, including theater, national television, and award-winning films. He is completing a novel set in the 1960s.

Tagged: Anka Muhlstein, Camille Pissarro, Cezanne, Impressionism